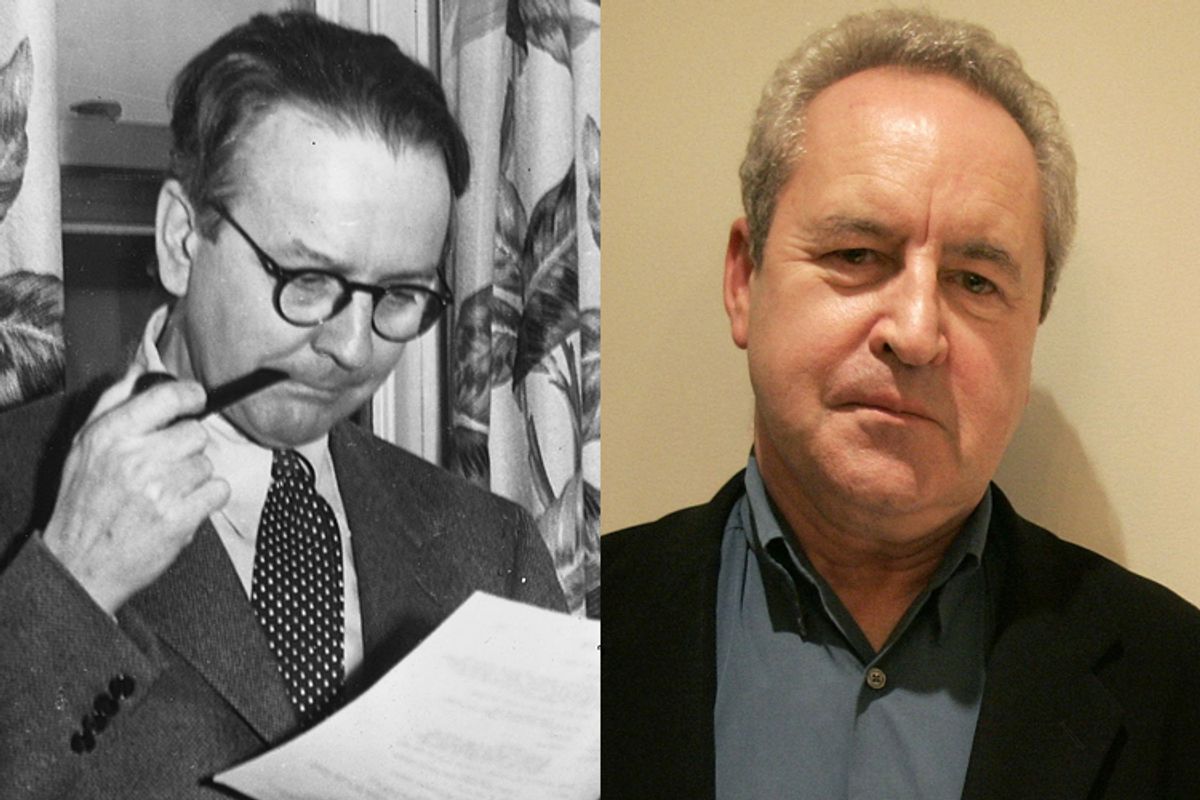

In 1986 Irish critic Seamus Deane wrote that with the appearance of John Banville’s first few novels, “It was obvious that an important new writer had arrived, although in what his importance consisted was not clear.” Today, after 24 novels, six plays and five screenplays, it still isn’t clear. After decades of being compared to Nabokov and comparing himself to Henry James, it now seems that the greatest living high-art novelist in the English language has set his sights a bit lower. With “The Black-Eyed Blonde,” Benjamin Black -- Mr. Hyde to Banville’s Dr. Jekyll -- seems to have completely taken over his personality. Black has now written eight of Banville’s last 10 novels.

I suppose it’s none of my business, but I find it irritating that Banville chooses to write his mysteries under a pseudonym, then goes out of his way in every interview to remind us that he uses a pseudonym. Graham Greene didn’t need a pseudonym for what he called “entertainments” such as “The Third Man,” “The Confidential Agent” and “Ministry of Fear.” Maybe he should have used a pseudonym for his more serious novels and put his own name on the entertainments because they’re better novels.

Banville’s serious novels are far superior to Greene’s serious novels, but his entertainments aren’t as entertaining. With “The Black-Eyed Blonde” Banville seems to be trying to up the ante for Black.

Mickey Spillane once told an interviewer, “If Thomas Mann sold, I’d write like Thomas Mann.” I think a gorilla with a laptop could come closer to Thomas Mann than Mickey Spillane, but I also don’t think that Mann was capable of writing detective stories of any kind, at least not good ones. It’s tougher than it seems. Raymond Chandler, though, was far better than Mickey Spillane, and John Banville can write like Raymond Chandler, as he has proven in his Quirke mysteries and now in his Philip Marlowe novel, “The Black-Eyed Blonde.” Whether Banville -- or Black -- can write better than Raymond Chandler is another matter.

Chandler was 51 when he published his first novel, “The Big Sleep,” in 1939. Lovers of crime fiction who come to his work for the first time are often surprised how little he actually wrote. Of his other six novels, “Farewell My Lovely” (1940) and “The Long Goodbye” (1953) are generally regarded as the best. There isn’t much more, just a few volumes of stories, some essays (including the oft-quoted “The Simple Art of Murder,” which gave the world and Martin Scorsese the term “mean streets”) and a film script for “Double Indemnity” (1944), co-written with Billy Wilder for his 1944 film, and “Strangers on a Train,” from which Hitchcock apparently retained only the dialogue for his 1951 thriller.

From that slim oeuvre, Chandler helped create film noir and spawned a literary genre that has mutated to graphic novels in this century. A very good case could be made that Chandler has had more impact on both high art and popular culture than any other American writer.

His influence extends all around the world. Chandler was lauded by Auden, admired by Camus, and idolized by Haruki Murakami, who said in an interview a few years ago, “Philip Marlowe is Chandler’s fantasy, but he’s real to me.” He has his critics, too. “The atmosphere in these stories,” sniffed Borges in his “Lectures on American Literature,” “is disagreeable.” Of course, the atmosphere as well as the style is precisely why most of us go to Chandler. As Clive James wrote in a 1977 essay, “His style has lasted … His style is poetic, rather than prosaic” – precisely the reason that a good crime novel hack like Robert B. Parker couldn’t pick up Chandler’s ball and run with it, “Even at its most explicit, what he wrote about was full of implication.” Wilfrid Sheed said it another way: “Chandler could not describe a laundromat without freighting it with corruption and menace.”

Chandler is easy to parody. S.J. Perelman probably did it best in “Farewell My Lovely Appetizer”: “Her bosom was heaving, and it looked even better that way.” And ”A thin galoot with stooping shoulders was being very busy reading a paper outside the store … He hadn’t been there an hour ago, but then, of course, neither had I.” Steve Martin and Carl Reiner gave it a go in “Dead Men Don’t Wear Plaid”: “It was the kind of place where rich men went to meet rich women to have rich babies.”

But if Chandler is easy to imitate, tweed-wearing smart guys put him down at their peril. Martin Amis, for instance, tried to shoot down Chandler’s reputation back in 1997 as a setup for his own detective novel, “Night Train.” Amis’ soft-boiled mystery was deader than a city lost and beaten and full of emptiness.

Maybe that last line doesn’t make much sense in this context, but I like it, and Chandler wrote it. It’s from “The Long Goodbye,” the novel that Banville takes off from in “The Black-Eyed Blonde.”

In truth, Banville is better at plots than Chandler. In “The Simple Art of Murder,” Chandler criticized popular English mystery writers such as Agatha Christie for plots that “only a halfwit could guess.” But making my way through some of Chandler’s books, I wanted to send out for a halfwit because I can’t make heads or tails of the plot. Banville’s plots in the Black books and “The Black-Eyed Blonde” are smart and well thought out with almost none of the major potholes left in Marlowe’s trail. But this is a minor point; we don’t read Chandler for plot, we read him for that atmosphere that Borges found so disagreeable and for the language, the dialogue and Marlowe’s relentlessly undercutting wit.

How good is Banville’s impersonation of Chandler? See for yourself:

“Her hair was blonde and her eyes were black, black and deep as a mountain lake, the lids exquisitely tapered at their outer corners. A blonde with black eyes – that’s not a combination you get very often.” Rhythm, cadence, punctuation perfect.

“Sometimes I think I should lay off cigarettes for good, but if I did that, I’d have no hobbies except chess, and I keep beating myself at chess.” Sardonic, not too cynical, just fine.

“I felt like the wedding guest trying to unhook himself from the Ancient Mariner.” A tad too literary? Maybe, but then Marlowe sometimes referenced Proust.

“She had a way of batting things aside, things she didn’t like or didn’t want to deal with, that always left me hanging. It’s the kind of knack that only a lifetime soaked in money can teach you.” Spot-on; we know from the Black novels that Quirke shares Marlowe’s contempt for the rich.

“That tired old sign reading, ‘Fagots – Stay Out,’ was still behind the bar. That’s a thing I’ve noticed about Barney’s kind of people: they’re not very good at spelling.” I think Chandler would have written “pansy” instead of fagot or faggot.

“A guy came in who looked so much like Gary Cooper that it couldn’t have been him.” It might have been funnier if he had used Bogart instead of Cooper since Bogey played the best Philip Marlowe in “The Big Sleep,” but Cooper will do.

“She was one of those women whose sister would be beautiful though she just missed it herself.” I wouldn’t touch a thing in that line.

A would-be starlet impersonating a star “moistened her lips with the tip of her tongue and leaned her head back lazily, showing off her snowy throat; I guessed Barbara Stanwyck in 'Double Indemnity.'” Funny, and with a nice little in-joke since Chandler co-wrote the script for that film.

Aficionados will spot all kinds of playful, Nabokov-type allusions to other Chandler works. Marlowe calls a butler “jolly old Jeeves” -- you get points if you knew that Chandler went to the same English school, Dulwich, as P.G. Wodehouse.

“Cedric had steered us off Cahuenga, and we were traveling westward now along Chandler Boulevard. Nice street, Chandler, nothing mean about it: it’s broad and clean and well lighted at night.” Nice passage. Banville jams a lot of references into about 30 words. Cahuenga was where Marlowe lived (the address 615, the telephone Glenview 7537) until he moved to a house on Yucca in Laurel Canyon, presumably in 1952 when his creator moved him there while writing “The Long Goodbye.” Banville also slyly alludes to the “mean streets” of Chandler’s famous essay. By the way, the Chandler that Chandler Boulevard was named after wasn’t Raymond but Harry, the longtime publisher of the Los Angeles Times, the paper Marlowe read every morning.

Banville also plays tricks with time. “The Black-Eyed Blonde” is set after “The Long Goodbye,” which would place it in 1954 at the earliest. Yet, when Marlowe makes a late-night call to his old colleague in the DA’s office, Bernie Ohls, he interrupts Bernie watching a fight on TV. The fight was for the light-heavyweight championship between the challenger, Sugar Ray Robinson, and the champ, Joey Maxim, on June 25, 1952. I know that because my father was there, and he told me about it; it was at Yankee Stadium and it was so hot that night that Robinson, who was winning handily, couldn’t answer the bell for the 15th round. Unless Bernie Ohls’ television was getting signals from ‘The Twilight Zone," the author has placed the events of “The Black-Eyed Blonde” before those of “The Long Goodbye.”

Tough to figure what Banville was trying to do here – these Irishmen can be tricky. Then, Chandler’s mother was Irish.

In an author’s note, Banville writes, “In all the Marlowe novels, his creator played fast and loose with the topography of Southern California, and I have allowed myself the same license. Yet there were many details that had to be accurate and of which I was unsure. I therefore depended heavily on advice from a quintet of informants who knew the area intimately.” (One of these informants was Candice Bergen.) Some critics have chastised Banville for relying on secondhand information, for instance, David L. Ulin of the L.A. Times, who accuses Banville of “outsourcing the legwork.” Chandler’s true stylistic brilliance, Ulin claims, “is that out of his experience of Los Angeles he built a world both heightened and authentic … the failure of this novel is that it never pierces its own surfaces to evoke the city underneath.”

I don’t buy this Chandler’s ”experience of Los Angeles.” There were parts of L.A. that Chandler knew very well -- you can find the passages from his books with accompanying black-and-white photographs in a marvelous volume, “Raymond Chandler’s Los Angeles,” by Elizabeth Ward and Alain Silver. But there was a lot of it that he didn’t know well, probably the areas he was thinking about when he said that L.A. had “all the personality of a paper cup.” It’s worth knowing that he knew Santa Monica better and placed most of his prostitution, drug deals and murders in its fictitious re-creation, Bay City.

Contrary to popular belief, Chandler wasn’t really well acquainted with L.A., which was probably the reason he was able to evoke it so well. Wilfrid Sheed noted that Chandler, who was raised in England, “had a foreigner’s sense of the strangeness of America,” and this went double for Los Angeles, a city that both fascinated and repelled him.

Banville does a fine job with Los Angeles, especially considering he’s writing about a city that has changed much over the last 60 years. Anyway, he’s not writing about Los Angeles, he’s writing about Raymond Chandler’s Los Angeles.

A bigger mystery than any in “The Black-Eyed Blonde,” though, is why Banville chose to write the book at all. In the swarm of post-publication commentary, I’m surprised that no one has referred to an essay Banville wrote for the December/January 2008 issue of “Bookforum” on his love of pulp. Of Chandler he writes, “I consider the Marlowe books forced and even a touch sentimental for all their elegance and wit and wonderful sheen … Chandler perhaps labored too long and too hard at effecting the transmutation of life’s raw material into deathless prose. A far greater writer, James M. Cain, who was happy to keep it raw, who gloried, indeed, in the rebarbative, created a masterpiece, seemingly effortlessly, in ‘The Postman Always Rings Twice.’ “ After reading that sentence, I wished Hammett’s Sam Spade would slap Banville and tell him, “People lose teeth talking like that.”

Yes, “Postman” is a great book, but most of the rest of Cain’s oeuvre was filled with the kind of prose Pauline Kael called “the mythic, overwrought James M. Cainisms.” Third, one shouldn’t accuse a writer of sentimentality – or even a touch of it – when about three times a novel his own protagonist, Quirke, indulges in Jameson’s-soaked self-pity.

If Banville really thinks Chandler labored too long on his deathless prose, why is it that he, perhaps the greatest living writer of English prose, labored so long to re-create it?

I figure it this way: He decided he couldn’t catch Henry James, but there was an opening for Raymond Chandler and he took it.

Shares