Somewhere in middle age I returned to the quest, or, in its stripped-down version, the question of what exactly happened there when I was seventeen. In the midst of so much that was grown-up and responsible—deadlines, campaigns, movements, scholarly undertakings, motherhood—some crucial late-night part of the ongoing mental churning regressed back to the events of my adolescence, which were just too strange, and I wish there were a better word, to be permanently buried under the label of “mental illness” or some kind of temporary perceptual slippage. “If you see something, say something,” as we are urged in train stations today, and certainly I had seen something. Yes, it was something inexplicable and anomalous, something that seemed, in a way I could not define, to be almost alive. But this had also been the case with the oscillations at the silicon electrode, and it was still my responsibility to report them and bear the shame, if necessary, of bringing unwelcome, perhaps even incomprehensible news.

The circumstances of my return were not auspicious. The movement that had sustained me for more than a decade was crumbling under my feet. As my former comrades drifted away, to careers or, in a few cases, cults or prison, I could no longer imagine myself as a warrior. I was at best a soldier, sticking doggedly to the project of “social change” even when that meant serving in the most tediously compromised fragments of the left, where the idea was no longer to ignite the “masses” but to flatter, and thereby hopefully influence, people who were more influential than we were. More and more of my time was devoted to the feminist movement, but it too was often mired in useless discussion, such as attempts to determine our “principles of unity.” I got through the long meetings—often weekend-long meetings in windowless conference rooms—by trying to work out the prime numbers up to 200.

Meanwhile, my father succumbed to Alzheimer’s disease, which replaced that brilliant and complicated man with a partially melted wax effigy whose speech was increasingly limited to random word-sounds and chirps. Or maybe it was the nursing homes, as well as the Alzheimer’s, that worked this change in him, because if you take away all printed matter, occupation, and conversation, you will eventually get someone who kneels by the toilet to stir his feces with a plastic spoon, or so it has been my misfortune to observe.

Every few weeks I would fly to Denver to visit him, each trip a journey into the unbearable ugliness that humans manage to secrete around themselves out of plastic and metal and short-haired, easy-to-clean carpeting material: the airport, the interior of the airplane, the corporate chain hotel, predictable down to the free cookie offered to each arriving guest. And then there was the nursing home itself. Was I depressed because my father was dying or already dead, depending on how you evaluate these things, or because I had to spend so many hours in a place that made death seem like the best remaining option, if not something to be urgently desired? Moss green and salmon, no doubt thought to be an inoffensive, gender-neutral combination, made up the color scheme, except for the posters serving to remind us of the season—lambs and flowers in the spring, pumpkins in the fall, snowflakes in their proper time. And we needed those reminders, because fresh air was not allowed inside the nursing home, only air freshener.

Earlier, when things were going well, when the movement was thriving and before my father became a shell or my children turned into teenagers, bent on individuating themselves from me as if I represented a potentially contagious condition, I could handle a world without transcendence or even the memory of transcendence. But in addition to everything else, my second husband, who I can say in retrospect was the big love of my life, got eaten alive by his sixteen-hour-a-day job as a union organizer and began to act like one possessed. I had been his eager helpmate—marching in picket lines, going to organizing meetings, welcoming insurgent truck drivers, factory workers, and janitors into our appropriately modest home—but now he was too preoccupied to reliably hear me when I spoke or notice when I entered a room. With my human environment falling apart, the repressed began its inevitable return.

The story of the years leading up to my return to the old questions can best be summarized as a series of measurements and chemical assays: the increase in amyloid protein in my father’s brain and the corresponding decline of serotonin in my own; the uncertain tides of estrogen and oxytocin, the diurnal rise and fall of blood alcohol, caffeine, and sugar levels. Simmer all this together for many months and you get a potent toxin, which seemed to come at me in waves. I can remember the luncheon hosted by a countywide women’s organization, probably on a Saturday afternoon in late February. All very jolly and heartwarming, until I happened to look out the window of the Long Island catering hall where we were gathered and saw the imminent menace. There was a gas station and an intersection under a pearly gray sky peppered with factory emissions; there was a parking lot mired with the black remains of snow; there was no hope. The award ceremony itself was a mockery, because anyone could see that the people presiding over it were dying right in front of us, if not actually dead, and that rigor mortis had already hardened their smiles into grimaces. And I was not a passive or reluctant participant in this event. I was the one who got the award.

The name for my condition, I discovered, was “depression,” which I learned from a 1989 op-ed column William Styron wrote about Primo Levi’s suicide. What surprised me was the term, “depression,” which seemed far too languid to apply—an insipid “wimp of a word,” as Styron himself put it, for “a dreadful and raging disease.” I went along with the diagnosis, therapy, and medications, but not without internal reservations. You can talk about depression as a “chemical imbalance” all you want, but it presents itself as an external antagonist—a “demon,” a “beast,” or a “black dog,” as Samuel Johnson called it. It could pounce at any time, even in the most innocuous setting, like that award luncheon or in a parking lot where I waited one evening to pick up my daughter from a school trip. What if her school bus failed to return? What if it had crashed somewhere? Even when I had her safely in the car, it was all I could do to get us home and rush into the bathroom for a fit of gagging and trembling over how close the beast was getting.

It was despair that pulled me back, as a mature adult, to the ancient, childish quest. I could not go on the way I had been, dragging the huge weight of my unfinished project. The constant vigilance imposed by motherhood, along with the pressure to get assignments and meet deadlines, had trapped me in the world of consensual reality—the accepted symbols and meanings, the highways and malls, meetings and conferences, supermarkets and school functions. I seemed to have lost the ability to dissociate, to look beneath the surface and ask the old question, which is, in the simplest terms, What is actually going on here?

Or maybe depression in its demon form awoke me to the long-buried possibility that there exist other beings, agents, forces than those that are visible and agreed upon. I wish I could draw some clear lines of causality here, but there are no primary sources to refer to, no journal or even any random notes to my future self.

But when I did try to return to the old questions, very furtively of course, despair and a kind of shame followed me and blocked the way. The impasse was this: If I let myself speculate even tentatively about that something, if I acknowledged the possibility of a nonhuman agent or agents, some mysterious Other, intervening in my life, could I still call myself an atheist? In my public life as a writer and a speaker, I had always been a reliably “out” atheist. This was my parents’ legacy, and a deeper part of my identity than incidentals like nationality or even class. At some point in the eighties I published an essay-length history of American atheism that unearthed the stream of working-class atheism from which I was descended. I won awards and recognition from organizations of “freethinkers” and humanists. When the subject came up, which it was bound to in our largely Catholic blue-collar neighborhood, I told my children that there is no God, no good and loving God anyway, which is why we humans have to do our best to help and care for each other. Morality, as far as I could see, originates in atheism and the realization that no higher power is coming along to feed the hungry or lift the fallen. Mercy is left entirely to us.

I was no longer the kind of scornful, dogmatic atheist my parents had been. When I read the book of Matthew closely in my forties I was startled by the mad generosity Jesus recommends: Abandon all material possessions; give all you have to the poor; if a man asks for your cloak, give him your coat as well; and so forth. If you’re going to help the suffering underdog, why not go all the way? But then, as the Bible drones on and Jesus fades away to be replaced by “the risen Christ” holding out the promise of immortal life, the message takes on a nasty, selfish edge. How can you smugly accept your seat in heaven when others, including probably some of the ones you love, are confined to eternal torment? The only “Christian” thing to do is to give up your promised spot in heaven to some poor sinner and take his place in hell. Far easier, it seemed to me, to profess atheism and accept the moral obligations a Godless world entails.

As for the mortality that atheism leaves you no escape from—do not for a moment imagine that this was the source of my depression. I was old enough, in my forties, to sense the beginnings of decline, first announced by backaches and the need for reading glasses. What I feared was something more suitable to a depressive: the unthinkable possibility of not being able to die. Suppose that my brain had been excised by evil scientists and was being kept alive in a tissue culture medium, then subjected to electrical shocks that varied ingeniously so that my mind could never become habituated to the pain, and that this could be done for centuries, millennia, forever. Or that my body had survived some catastrophic disease, leaving me in a “locked in” condition, unable to move or communicate. If you can imagine these states, then you know that a kindly god would not promise “eternal life.” He or she would offer us instead the certainty of death, the assurance that somehow, eventually, the pain will come to an end. Why believers should forgo this comforting certainty, which is so readily available to atheists, is a mystery to me.

My activism required me to be tolerant, to incline my head a little when others bowed theirs, but all too often I was more challenging on the issue than courtesy allowed, once even picking a fight with a local liberal minister. He was trying to reassure me that his vague denomination had no active involvement with God himself and remained fairly open on the question. That wasn’t good enough for me, though. I insisted that the appropriate stance toward an omnipotent God, even the possibility of an omnipotent God, should be hatred and opposition for all the misery he allowed or instigated. Another time, I disrupted the happy revivalist vibe at a conference held in a black church because I was tired of hearing the clergymen who were my co-panelists exult in the unifying power of Jesus. I pointed out the number of women in the audience wearing head scarves, guessed at the number of Jews in attendance, and announced that I, an invited panelist, was an atheist by family tradition. Somehow I even managed to profess my atheism to an audience of striking janitors in Miami, all Hispanic and presumably Catholic or Pentecostal, to the irritation of the union officials who had invited me.

It wasn’t just family loyalty that held me back from potentially heretical speculations. The whole project of science, as I had first understood it way back in high school, is to crush any notion of powerful nonhuman Others, to establish that there are no conscious, subjective beings other than ourselves—no spirits, demons, or gods. An individual scientist may practice her ancestral religion with an apparently clear conscience, but once at work, her job is to track down and strangle any notion of nonhuman or superhuman “agents”—that being the general term for beings that can move or initiate action on their own. Thus, for example, the oscillations at the silicon electrode could not be the work of some malign creature lurking unseen in my lab: That was exactly the possibility that had to be eliminated, if only I could have found a way to do so.

The same impulse drives me today. If you hypothesize that certain strange noises in the house are produced by ghosts or poltergeists, I will tear the walls down, if necessary, to prove you wrong. Human freedom, knowledge, and—let’s be honest, mastery—all depend on shooing out the ghosts and spirits. The central habitat of spirits in our culture is religion, with the excess population flowing over into New Age spirituality, and nothing has ever happened in my adult life to incline me more approvingly to either.

At some point, close to what seemed to be the nadir of depression, I began to dig myself out, using tools that, I now realize, had always been at hand. I was by this time not only a journalist churning out weekly eight-hundred- to thousand-word columns and essays on topical matters, but an amateur historian. The short pieces entertained (and financially supported) me, while the longer historical excursions fed my mind, or rather the insatiable little creature within it that was always demanding fresh questions and fresh clues. Lab work had starved my intellect, but the form of science I turned to now, “social science,” which requires no glassware or equipment, opened up a feeding frenzy. At first I wrote books on relatively manageable issues related to class and gender in American society, and then, realizing I had nothing to lose, turned to much larger issues—too large, in fact, for any legitimate social scientist—like religion and war.

I had no reason to think that my new research interests had anything to do with the old metaphysical quest. Anything I dignified in my mind as “work” was about “politics,” in the broadest sense, and social responsibility—good, rational, mature concerns that could be justified by my activist involvements and concern for my children’s future. But my intellectual agenda was hardly just a matter of rational, liberal decision-making. I had not come out of solipsism into a world of gemütlichkeit and good cheer. To acknowledge the existence of other people is also to acknowledge that they are not reliable sources of safety or comfort.

Metaphorically, you could describe the situation this way: I am adrift at sea for years clinging to a piece of flotsam or wreckage, alone and prepared to die. Then I get rescued by a passing lifeboat, packed with people who pull me in and give me food and water. But just as I am rejoicing in the human company, I begin to notice that there is something not quite right about my new community. I detect uneasiness and evasion in their daily interactions. There are screams and groans at night. Sometimes in the morning I notice that our numbers have shrunk, though no one comments on the missing. I have to know what is going on, if only for my own survival. Hence the frantic turn to history: If these are my people and this is my community, I need to know what evil is tearing away at it, where the cruelty is coming from.

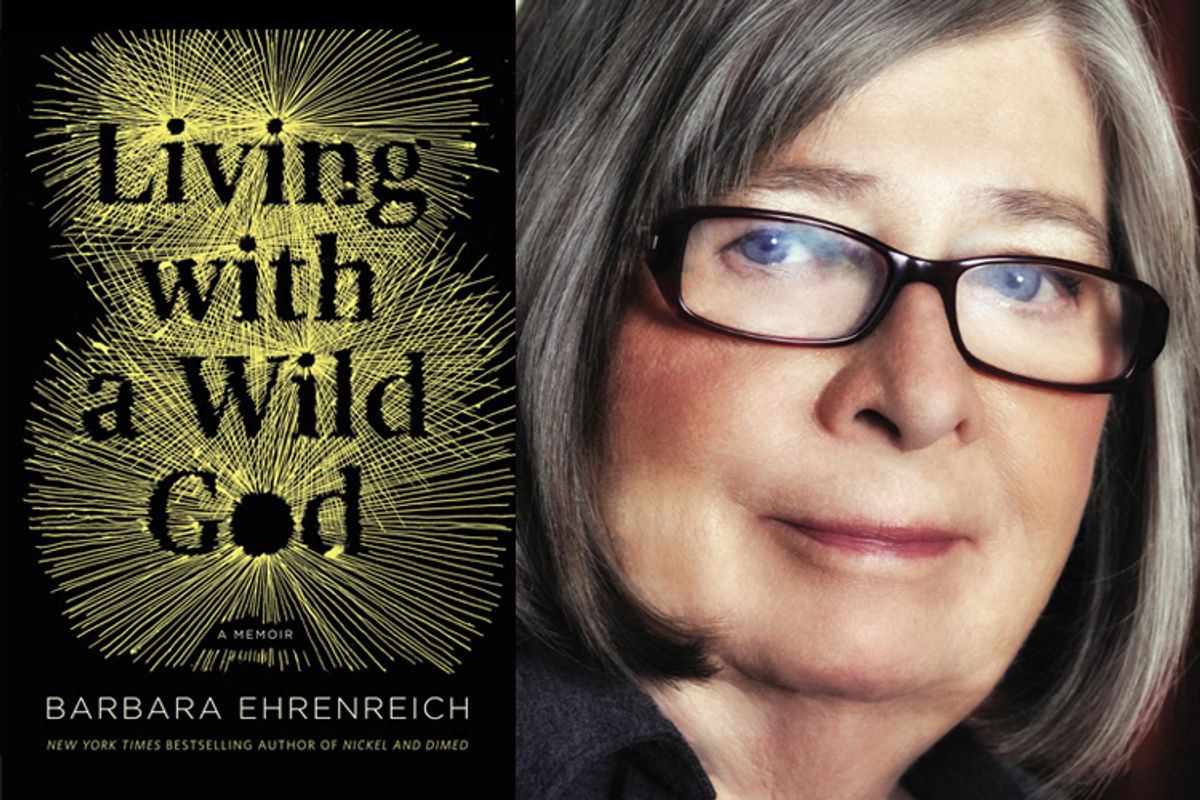

Excerpted from the book "Living With a Wild God: A Nonbeliever’s Search for the Truth About Everything." Copyright (c) 2014 by Barbara Ehrenreich. Reprinted by permission of Twelve/Hachette Book Group, New York, NY. All rights reserved.

Shares