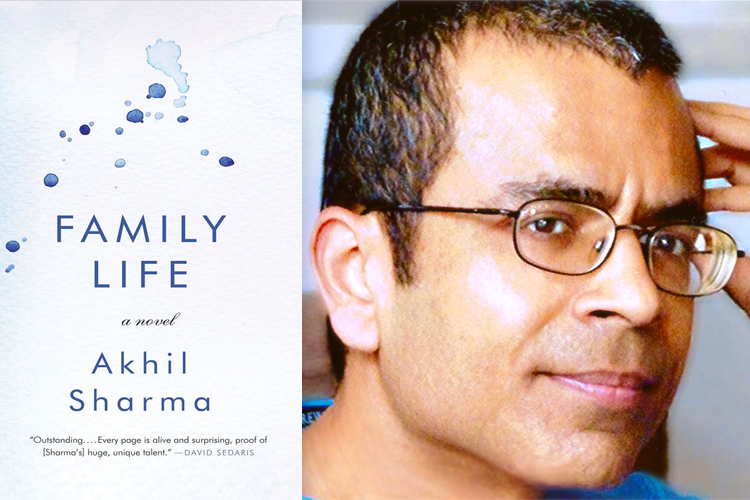

It was with a sense of genuine excitement that I sat down to read Akhil Sharma’s “Family Life,” which I and many others in the literary world have been eagerly anticipating for a very great while. Though he’s published only one previous novel — “An Obedient Father,” in 2001 — that book was more than enough to establish its author as one of the leading lights of fiction in America.

Sharma’s novel, more than a decade in the making, tells the story of the Mishras, a family from Delhi that relocates to suburban America in the late 1970s. Not long after their arrival, tragedy strikes one of their two young sons, and the Mishras are forced to deal with hospitals, lawyers, insurance companies, and their anger and despair at their shared fate. “Family Life” is a novel of the immigrant experience, of course, but it is also a powerful coming-of-age story, as well as one of religious faith and the limits of familial loyalty.

The book is relatively slender — just over 200 pages — but packs the emotional punch of a much longer work. I lost all track of time while I was reading it, and felt by the end that I’d returned from a great and often harrowing journey. “Family Life” conveys the sense, as all great tragic novels do, of the extremes to which even the most humble lives can be driven by catastrophe, and the capacity of even the most ordinary among us to survive — and to survive, in fact, at any cost. To my own surprise, I found myself renewed after reading it, and imbued with a feeling of hope.

I spoke with Akhil Sharma at the Gramercy Tavern in downtown Manhattan, and was surprised to find that we spent most of our conversation laughing loudly — a little too loudly for our somewhat frumpy-looking neighbors. I shouldn’t have been surprised, however, come to think of it. “Family Life” itself is terrifying and hilarious by turns.

You’ve said that you want this book to be “useful.” Useful how?

Because the subject matter of this book is so important to me – illness, children in difficulty, the Indian immigrant community – I care a great deal about being able to provide comfort to people who are in a similar situation to the one that I and my family were in.

That seems like a very old-fashioned way to think about a novel.

It is, this idea that we can read books for guidance, or to not be alone. It is how I read books growing up and it is, to some extent, how I still read books. I think that books are fundamentally educational. For example, books teach us to practice loving. We read about imaginary characters and we learn to sympathize with strangers. This is an amazing thing.

From what I understand, this book is close — in its use of your own biography — to a memoir. Did you ever consider working in that genre?

You know, I am a fiction writer. I know how to write fiction well. I don’t think I can write nonfiction as well as I can write fiction and so I did what I thought I could do best. If I were a playwright, I might have written this as a play.

In the past you’ve resisted being called an immigrant novelist, which makes sense — it’s reductive, at best. Saul Bellow and Philip Roth were disgusted at being called Jewish writers. What I find interesting, however, is that people don’t seem to mind it quite so much now.

No. I still do mind the label. I mind the label because there is the sense of ghettoization in the term. I don’t want to be called an immigrant novelist. The book, I am OK with the book being called an immigrant novel. A more accurate description, though, would probably be that it is a coming-of-age novel or an illness novel.

You spent 12 and a half years writing the book and produced something like seven thousand pages. Seven thousand pages. How did you cope with that? What was it like?

Awful. I felt crazy. I wrote with a stopwatch. I kept it by my keyboard. My goal was to write for five hours every day. If a phone call came, I would stop the stopwatch. If I checked my email, I would stop the stopwatch. I measured my productivity based on time instead of word count because I could write plenty of pages without them going anywhere. Having the stopwatch read five hours meant I had proof that I was not being lazy, that I was actually working.

When you produce 7,000 pages you have basically written 35 novels. I tried many different points of view. I had many different characters and plot points. All this contributed to the sense of just flailing. About four years ago, there was actually a completed draft that my editor wanted to put into copy editing. I was ready to do it and then backed out at the last moment because I felt that that draft was too dark. It wasn’t full of life the way I wanted the book to be.

In what ways, exactly, did that draft differ from this final version?

It was in third person, this is in first. Much of that draft was told from the point of view of the father. Here it is from the point of view of the child. There was much more about alcoholism.

Knowing how long you spent working on the book, I’d been afraid that I might find it somehow clotted, either emotionally or verbally. How did you steer clear of this?

I don’t really revise. I tend to rewrite. When I would finish a draft, I would start the next draft by opening a blank document. This causes each draft to remain spare. Only what demands to be remembered stays in the new draft.

I had the sense, reading “Family Life,” that I could shake it and not a single word would fall out. Everything felt necessary.

That is the aspiration.

Was there any sort of breakthrough which led to the novel becoming what it is, or was it a steady progression?

I decided as an experiment to remove certain sensory elements which tend to make dramatized reality visceral. I removed, sound, smell, feel. This solved a very important problem I had been having, which was that the plot of the novel was too slight to keep dragging forward the scenes and the narrative. By removing these elements of the sensorium, I made scenes less visceral and so the reader could read them more quickly. This meant the novel needed much less plot. In many way what I did was reverse of certain things that Chekhov does. Chekhov relies on the stickiest elements of the sensorium: sound, smell, feel. These are the things which create the strongest sense of present tense. When you read Chekhov, everything has an even gray tone. When you read “Family Life,” everything has an even white tone. It is almost like when you paint on paper and you can see the paper through the paint.

Are you anxious about the book coming out?

When I was writing the book, I kept just wanting the book to be over. Now I want the book to do well. If the book were to sell a million copies I would want it to win a prize. This is why I think for a writer the most important thing is to just try to feel certain that one has done the best one can.

What does it feel like for the project finally to be done?

After almost 13 years of daily work, I still have the fear that I am going to be forced to sit back down at my computer and start working.