I’ll admit, prior to Tuesday, April 22, I wasn’t clamoring to try a virtual reality headset. My feelings on the technology shuffled between fleeting curiosity, light skepticism and downright luddism.

I’m not a gamer, so I had little interest in Sony’s Project Morpheus. And though I’m a Facebook user, I was squeamish about the social media giant buying Oculus Rift. It already knows my online habits and has mountains of user data; did I really need the social media site to suck me into its own version of reality?

I was sure there were world-saving, practical applications for devices like Oculus Rift: Testing car safety in virtual crashes, performing virtual reality surgeries and doing virtual search and rescue drills. I had no doubt that the technology was innovative, but it didn’t feel like it was marketed toward a person like me. What was my application? What were the capabilities beyond video games and Facebook?

At Tribeca Film Festival’s Innovation Week, I was offered the chance to test Oculus Rift, and experience the mind-blowing capabilities of the technology.

* * *

Oculus Rift was created by 21-year-old Palmer Luckey, founder of Oculus VR, the company that created Oculus Rift. Luckey’s desire to experience video games in an immersive 3-D world led him to build his first virtual reality prototype at age 16. He then went on to launch a Kickstarter to fund his virtual reality company and headset. Oculus VR aimed to raise $250,000 — and actually raised $2,437,429, sparking a craze for virtual reality headsets and even prompting Facebook to purchase the company for $2 billion earlier this spring.

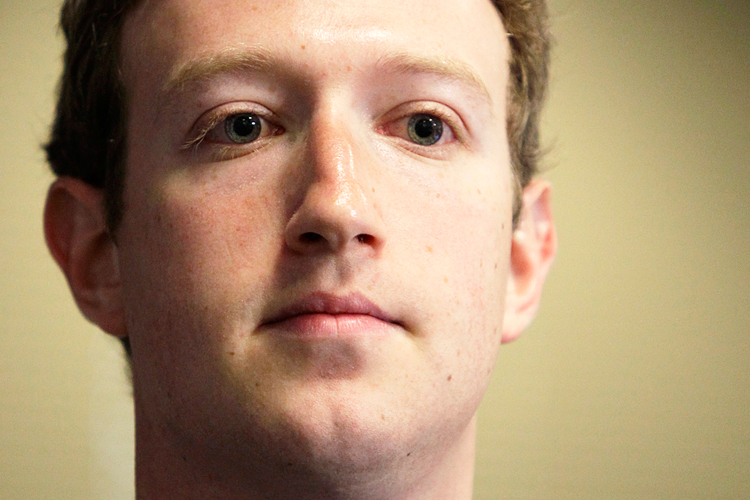

“This is really a new communication platform,” Zuckerberg stated in a press release at the time. “By feeling truly present, you can share unbounded spaces and experiences with the people in your life. Imagine sharing not just moments with your friends online, but entire experiences and adventures.”

The backlash was swift and fierce. Gamers and grass-roots techies felt the community-funded company had sold out. Some worried Oculus would stray from its gaming roots, while others had misgivings about Zuckerberg’s notoriously privacy-averse tech empire getting its hands on the groundbreaking technology. Nonetheless, yesterday the FTC approved the sale of Oculus VR to Facebook.

Zuckerberg is not alone in wanting to use new technology — artists are using different modes to bridge the gap between coding and creativity. The Oculus Rift demo was one of the many hybrid art and technology installations sharing narratives at the Film Festival’s Storyscape event. As I wound my way through Storyscape, I glimpsed several different attempts by artists to bridge the gap between computer code and creativity, hybridizations of art and technology hoping to key into something human — a piano whose sounds were composed by New Yorkers singing notes, an installation that gave a window into the U.S. immigration system, for example.

And then I found Oculus Rift.

Tucked away next to the Bombay Sapphire bar, I saw several seated girls were strapped into what looked like opaque snorkeling masks; large headphones covered their ears. The girls were in varying states of motion; one stared straight ahead, deathly still. Another intermittently looked left and right. A third girl was swirling her head around, as if she was experiencing the effects of some psychotropic substance.

What were they seeing? What was this exhibit? I had to test it. I walked over and asked if I could try.

I was surprised to see that Oculus Rift was not being used for Facebook or gaming. Rather it was the technological medium for artists James George and Jonathan Minard to present their specially created documentary. James George set me up and asked if I’d ever tried virtual reality before. “No, I haven’t,” I replied nervously.

As he fitted me with “goggles,” as he jokingly called them, he explained the project. I’d be watching a film called “Clouds” about the intersection of creativity and computer science. (Computation, it seemed, was was woven into everything.) The story would change and shift with my preferences. Questions would pop up and if I stared at them long enough they’d transport me to a different part of the documentary. Interactive buttons that I activated with my eyes peppered the experience.

All of your visual interactions are controlled by your sight and movements of your head. To start the documentary I shook my head right and then left, connecting my line of sight to interactive spheres. Visual possibilities are not limited to what is directly in front of you. There is more to be explored up, down, left and right — a virtual field that envelops you, tricking even your peripheral vision.

When I first put on Oculus Rift I was frustrated, the picture was blurry and I was unable to read the names and titles of the scientists and artists explaining the world of computation. My heart sank; I had a chance to test out virtual reality and my headset had a technical glitch. “Some innovation,” I thought.

By chance, and a moment of fidgeting, I realized the issue: The Oculus Rift headset was slightly too big. If Oculus sagged, the image sagged. It wasn’t a technical glitch, but rather an easy mechanical fix. Adjusting the headset I was suddenly flooded with an amazing and clear image. Stylized digital heads of scientists and artists spoke directly to me, and waves of gorgeous 3-D images enveloped my sight.

My senses were tricked, and I was in it. I traveled through a vortex of white coral, and an expansive void of darkness punctuated with geometric lines of light. I looked up and down, left and right, swirling my head. I was only mildly aware that I look nuts from the outside. I was slightly aware that despite being comfortably seated, my heart was racing as if I was speeding through space.

There were, however, moments when I was jerked back into actual reality. I had to wait for sections of the documentary to load, and at one moment I was sure that it had ended, before brilliant images burst onto the screen. There were also physical downsides to the technology. By the end I was tinged with motion sickness, slightly concerned by my racing heart and craving human interaction.

Taking Oculus Rift off was like breaking through the surface of a pool. I took a moment to breathe and reacclimate to the world around me. “I was really in it!” I blurted out to George. “It was like I was in my own special world.”

He laughed, “Well, that’s the point.”

For the first time I understood why Oculus Rift, and virtual reality more broadly, were so incredible. (And maybe even why Mark Zuckerberg paid billions for the technology.) Virtual reality makes 3-D movies look like a carnival sideshow by comparison.

The most marvelous part was physically experiencing the diversity of the technology. The program I watched was neither video game nor social media. I watched a documentary made by artists and developers. It was a virtual reality application I hadn’t registered, and one that I’d actually use for all manners of events — faraway or sold out concerts, made-for-virtual-reality television or movies, a virtual lecture series.

It also made me more acutely aware of the power Facebook has over this technology. I sincerely hope that the company does not limit the virtual scope of reality, and that artists, scientists and gamers can continue to create a world within Oculus Rift.