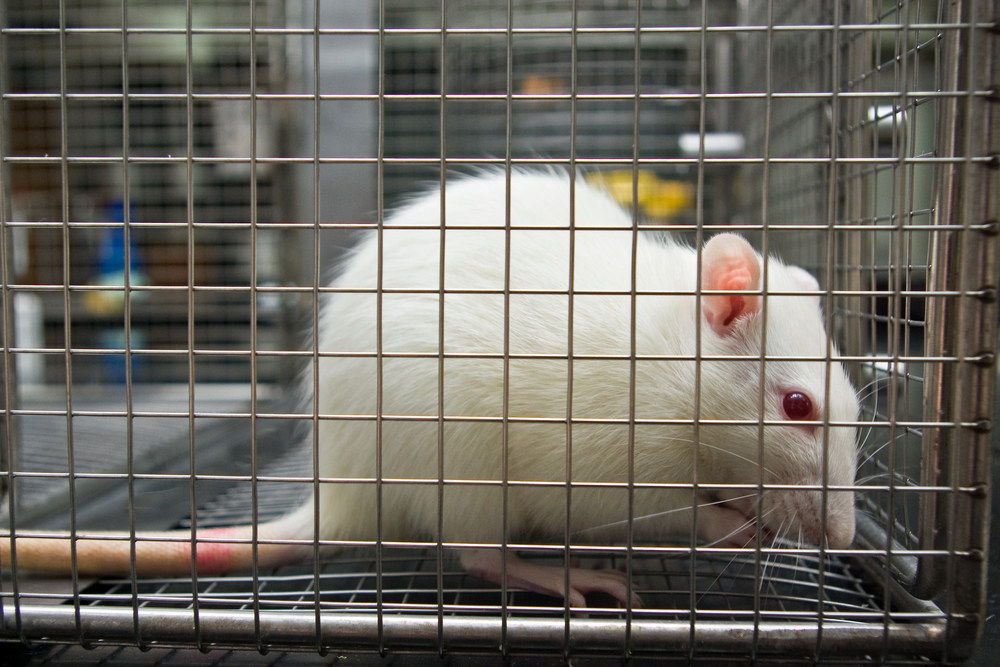

A new study from McGill University in Montreal is undoubtedly sending shockwaves through the scientific community — or at least laboratories that employ mice in experiments. In this study, published in the journal Nature Method, the research team, led by Dr. Jeffrey Mogil, looked at how mice react to their laboratory handlers, and levels of pain.

Their results? Mice fear men, but not women.

The research team used the “mouse grimace scale.” The scale measures the mouse’s pain responses to men and women. It also measured the “grimace” response to scents from male and female humans and other animals. Men and male scents provoked less pain, while women and female scents caused no change in pain tolerance.

In this case, feeling less pain (in the presence of males) is not a positive response. In fact it pushes mice to ignore something harmful, the way an athlete might play through an injury and worsen the damage.

Pain was not the only indicator. In the presence of men or male smell, body temperature rose along with levels of the the stress hormone corticosterone. Mogil believes this response is probably evolutionary. Male mice are territorial, and the stress is caused by a feeling of competition.

“People have not paid attention to this in the entire history of scientific research of animals,” Mogil told the Verge . “I think that it may have confounded, to whatever degree, some very large subset of existing research.”

It’s difficult not to question what this means for decades worth of studies that used mice in experiments. However, Mogil doesn’t see his study as ruinous for the scientific community. He views the findings as a potential to solve some outstanding mysteries. Salon spoke to Jeffrey Mogil about what spurred him to do this test and what it means for the future of scientific studies. The interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

What was your impetus for doing this study in the first place?

The experiment, basically, was an attempt to investigate a little bit of a lab legend. So over the years people came up to me periodically from my lab and gave me a story that went something like, “We’re doing a pain experiment on mice, and we injected the substance that’s supposed to cause pain behaviors, and we didn’t see any pain behaviors and we thought something was wrong, but then when we went and looked at the video later it turned out to be fine. The mice were just waiting for us to leave the room.”

And this was something that people sort of whispered about in meetings. That experiments could be causing analgesia, or pain inhibition. So I basically said, “I keep hearing this story, and everyone thinks that this might be true, but no one’s ever gone to see if it is true. So let’s go and look at it properly.” And so we did.

And we found very quickly that it was half true. That experimenters do produce analgesia, but only if they’re male experimenters, not female. And that was a huge surprise because that’s not what we were expecting, and that’s not what everyone was whispering about. And so the question is, “Why?”

And subsequent experiments showed that this really has nothing to do with pain, per se. Men and olfactory stimuli related to men, or males anyway, produce stress, and stress is well known to produce analgesia or pain inhibition. So the reason we were seeing this effect on pain is simply because there was stress there produced by the male experimenter.

Could you go into more of the specifics of the experiment?

So, the problem, of course, is that there are 30 different experiments. But the first main one, I suppose, involved a pain stimulus — an inflammatory stimulus. We have to measure the pain somehow. We did that in a number of different ways but in the main experiment we did it by measuring facial expression, which is a measurement system we developed a few years ago, basically looking for grimacing. And in the first experiment, essentially, the mice were injected and a video camera captured facial expressions and either no one was in the room, which is the usual situation, or there was a male experimenter in the room reading a book, or there was a female experimenter sitting in a chair reading a book. And when the male experimenter was in the room there was less pain. And that male could be replaced by a T-shirt, or bedding material from any number of male mammals, or just vials of the appropriate chemicals that are released from the armpit, and we got the same effect.

Any tips to mitigate this effect? The obvious one is to have a woman do the test. But I read something about having a man sit in the room for 45 minutes to have the mouse acclimate —

Yeah, that ultimately would solve the problem. I don’t actually expect anyone to do that [sit in the room], but it would solve the problem. Really, the thing that has to happen, is people have to put this information in their methods section, pure and simple.

I read that this doesn’t just affect behavioral experiments but also medical experiments, because a stressed cell will behave differently. Is that true?

That’s just speculation. So we don’t have any data on any non-behavioral experiment in the paper. But I speculate that cells that are done in biochemistry or physiology experiments — where you’re just doing experiments on cells, there isn’t even an animal there — those cells came from an animal that in the last second of its life had either a high or low stress level, and it seems very reasonable to expect that the physiology of those cells might be different depending what the situation was, and ultimately who sacrificed the rat. But whether that’s true remains to be actually demonstrated.

Is there a way to test that?

Oh yeah, sure. I mean, people can simply go back and look. What I’m hoping is going to happen is that people are going to go back and look at their old experiments and say, “OK, so this experiment was done by John and this is the way that it worked out, and that experiment was done by Betty, and that’s the way it worked out, and if there are differences.” They’re going to notice. The same experiments, maybe exactly the same experiments, simply done by different people or with different people providing the tissue, revealing different results.

So I’m hoping that this finding is going to resolve a whole lot of existing mysteries in the literature. People are sort of painting this as bad news, but I actually think it’s good news; we might be people to figure out something that’s been confounding us for a long time.

As a journalist who writes about studies, do you think that other mistakes have been made in studies that would compromise results?

Again, I don’t think “mistakes” is the right word. There’s been a lot of talk over the past year or so about how animal research doesn’t replicate well. And people that say that, they always put the blame on the findings, they’re false positive findings. I think what this shows that the findings aren’t wrong. It’s very likely that everyone is right. It’s just that they’re right in their particular environmental conditions. Which are different from the environmental conditions in another lab.

So it’s not that one lab is right and one lab is wrong. Or that they’re both wrong. They’re both right. It’s just that biology is more complicated than we think. And we haven’t figured out what those environmental conditions are that interact with whatever it is you’re studying. And this is just the perfect example of that. This is something that one lab could find one thing and another lab could find another thing, and if you don’t know that the gender of the experimenter makes a difference, you’re going to think that one lab is right and one lab is wrong, but both labs are right. One lab found what happens when stress levels are high, and another found when stress levels are low.

I’m not claiming that all scientific findings are true, of course. Everything needs to be replicated and some things are and some things aren’t.

Do you have any next steps?

Well, look, one next step, I also have a grant to see if this is true in people. I think it very well might be true in people. But I would expect that if it’s true, it’s going to be a far smaller effect and far shorter lasting. So it’s going to be tough to show, but we’re going to try.

But I think it’s really more important at this point, not what my next steps are but if other people try to find the same phenomenon in their own labs. So I’ve already gotten an email or two from people who claim to see the same thing. One in dogs, which is interesting. So you know, we’ll see. It should be an interesting year of hearing reports about this sort of thing and just how broad it is.