Jose Antonio Vargas first got on a plane when he was 12 years old. That morning, his mother woke him up, told him to grab a few things and put him in a cab to the airport, where he left poverty and the Philippines for a better life with his grandparents in the United States. That was in 1993. He hasn’t hugged his mother since. Legally, he can’t visit her and she can’t visit him.

Vargas is an undocumented immigrant. When he came to America, he had a U.S. residency permit in his hand, but it wasn’t until he was 16 that he learned it was fake. Two decades later, he is stuck: barring marriage, there is no way for him to become a legal citizen in the only country he really knows. If he left to visit his mother, for instance, he probably wouldn’t be allowed back. And if his mother tried to visit him – well, she has tried, actually, and according to the U.S. government she poses too great a risk of overstaying a tourist visa, meaning she’s just too poor.

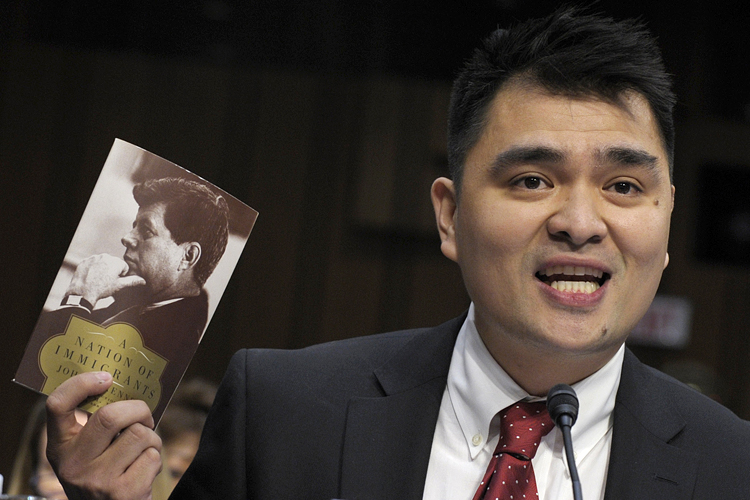

In 2011, Vargas decided to “come out” as undocumented and to do so with a media splash, announcing in a piece for the New York Times that he, a Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist who worked at the Washington Post, was one of the more than 11 million people in the United States who have families and jobs and live here, but every day risk deportation and the loss of all of that. His driver’s license was revoked soon after.

That story is told in a new film, “Documented,” in which Vargas explains that his decision to come out as undocumented in a country that deports more than 1,000 people a day was the culmination of years of “feeling like a coward.” He had kept his legal status a secret, not wanting himself or his family to get in trouble, but it became harder to keep with each deportation. “I had to do something.”

“Documented” is written, produced and directed by Vargas and it is a film, primarily, about Jose Antonio Vargas. It is not a comprehensive film about immigration in the United States: It does not delve into why a nation full of people whose families are from somewhere else – a nation founded by illegal immigrants who literally stole other people’s land – acts so harshly toward those who come here seeking only a better life. It doesn’t speculate on why, for instance, the very people most vocal in their opposition to immigration from brown countries are the same who demand amnesty for white Europeans, though perhaps that doesn’t require elucidation.

That the film is focused on Vargas and not so much others in his situation is not a critique so much as an explanation of what Vargas is trying to achieve. By highlighting his own story, he hopes to show the average American that undocumented immigrants aren’t just outside Home Depot, but all around them: teaching their kids; nursing them back to health; telling their stories on the news. We learn how his grandfather, a $10 an hour security guard, orchestrated his coming to America, believing even the modest, working-class life he could offer would be better than growing up poor in the Philippines. We learn how he struggled to assimilate before becoming one of the most popular students at school. We learn that he didn’t talk to his mother for more than a decade, resentful that she put him on a plane but never came herself.

When the film does break from Jose’s personal story – which succeeds in putting a face on the millions of faceless immigrants – it does so to highlight the plight of “dreamers,” the 1 million or so undocumented immigrants named for a bill, the Dream Act, which if enacted would provide a path to citizenship for those who were brought to the United States illegally by their parents, so long as they go to college or enlist in the military. Currently, there is no such path for these people, and even this moderate reform couldn’t make it past the Senate a few years ago, a defeat that Vargas credits with spurring him to break his silence.

In his film and in an interview with Salon, Vargas stresses his concern for all immigrants, but his focus on dreamers – people like him – might leave some thinking that not all undocumented people are so deserving: that those who were brought here as kids, as opposed to those who came here as adults, are more worthy of amnesty – and even then only so long as they study hard or join the Army.

Perhaps only some dumb white people could possibly draw such a conclusion, but then there are probably more than 12 million dumb white people in the United States. Still, Vargas’ approach of addressing white America with the relatively easy sell of the most “Americanized” of the country’s immigrants does seem to work on those for whom it is intended. For example, while filming at a bar in Birmingham, Alabama, a drunk patron interrupted an interview Vargas was doing to offer his constitutionally protected opinion on his state’s crackdown on immigrants: “Get the mother fuckers up out of here, that’s what I agree with,” he said, his girlfriend begging him to please, honey, don’t make a scene. “Get your papers or get out,” he slurred, turning to Vargas to ask directly: “You got your papers?”

Vargas is patient to the point of sainthood, informing the man that while he might look a little different, and as a matter of fact he does not have his papers, the United States is also the only country he really knows: He grew up here, went to college here and made a career here – there is no other home for him to go back to anymore. He loves this country and would be happy to go to the end of a line, were such a line for citizenship available to him (it’s not, a fact even this white ally was privileged enough to be ignorant of before Vargas came out). Vargas’ messaging might make some groan here in a country that is nowhere near as exceptional as its rhetoric, and which is more likely to deport an undocumented immigrant than award one a prize, but it does make the xenophobes in his film stop and think. Nationalist rhetoric is often ugly, but in the service of tricking some reactionaries into supporting a more humane policy toward those who through an accident of birth were born on the other side of a border, even Noam Chomsky might look the other way.

Vargas spoke to Salon to discuss immigration politics and his new film, which opens in theaters next month before airing this summer on CNN.

As you note in the film, there are up to 12 million undocumented immigrants. So did you at all fear that by focusing on yourself you’d be seen as ignoring these other people’s stories?

Oh my god, absolutely. That was an absolute fear of mine, especially because some people say I’m not the “typical undocumented person,” but what is the typical undocumented person? Are we not supposed to be “successful”? I mean, that’s the thing. There were many factors as to why I decided to come out as being undocumented. One of them is because I look the way that I look; I don’t look like the “stereotypical undocumented” person. The other thing is because I grew up in American newsrooms and I wanted to in any way I can not only challenge, but as much as possible help other journalists better cover this issue, which is one of the defining civil rights issues of our time that strikes at the heart of a demographically and culturally changing America.

That’s why my original vision was to feature other people and not make it about me. I figured I’d already written the New York Times story. But a film kind of – you can’t tell the film what it is, so it became apparent that it couldn’t kind of escape how my one individual personal story folds into the larger narrative, and that happens especially around the time of DACA, the deferred action for childhood arrivals, was announced – the fact that, as somebody who was over the age of 30, I didn’t qualify for it. And then the more we started filming the more my own friends were asking me about, “How can you possibly do a film and not include your mom?” And how do you report on your own mom?

When I was growing up and when I got to be an adult and a working professional, all I wanted to do was just, I’d give her money every month, and that was it. I didn’t want to complicate that. I felt like talking to her on the phone or writing her was just too painful. And then I realized that if I really wanted to show what this issue was about, I needed to show them what pain was. A really smart filmmaker recently told me that we learn a lot by feeling, and I would hope that anyone who sees the film and sees my relationship with my mother evolve, would understand what’s at stake with this issue.

Why was including your mother so important to you? Do you think it illustrates how the immigration system divides families?

I’m a big fan of James Baldwin. Baldwin says that nothing can be changed until it is faced. In many ways, including my mother in the film was my way of showing, look, a broken immigration system means broken families and broken lives. That’s what it means. This is not about the U.S.-Mexico border. This is not about border security. This is not about Republican or Democrat. This is about what mothers and fathers do for their kids … We have grown so accustomed to the media and the politicians framing this as a political and partisan issue that we’ve completely dehumanized it.

I think what ended up happening is immigrants have really become “the other” in America, culturally speaking. And this is why, by the way, I made a film – and I mean, let’s be honest about this, Charles: As you know, every day, I think 1,000 people get deported. What do I do? I make a film. I am undoubtedly one of the more, if not the most, privileged undocumented immigrants in America. And for us at Define American, which is this culture campaign group that I founded with some friends, culture trumps politics. We cannot change the politics issue until we change the culture around it; until we talk about what parents do for their kids as an act of love. That’s a cultural conversation.

For me, as someone who grew up and is gay, the immigrant rights movement has a lot to learn from the LGBT movement when it comes to personalizing and humanizing this issue. We are now at a time in LGBT rights when the CEO of Mozilla can be fired for making a donation. Because the culture has changed on LGBT rights, in a very short period of time. The same cannot be said for [immigrants] like me.

So I have done, what, 190 events in like 42 states in two and a half years? The most tragic thing for me is the number of people who use “Mexican” and “illegal” interchangeably? … I meet people all the time who are like, “I am an American citizen. I was born in this country, yet because I’m Mexican – because I’m brown – I don’t feel like I’m a part of this country.” That’s tragic. And that’s happening all across the country.

What do you think explains the opposition to immigration in the year 2014? Let’s be honest about this: You’re talking about immigrants as “the other.” Is it racism?

The new immigrant has always been “the other” in American history. With the Italians. With the Irish. What the Eastern European Jews went through. Of course, what’s different here is we are not “white.” For the most part, we think of Irish and Italians and Eastern Europeans – we put them in one category: “white.” Well, we are not white. Most of us are Latins; most of us are Asians. So that makes us different, or so society says. In the film, that’s why those two scenes – one in Alabama, one in Iowa – were so important in the film; it just shows you the deep level of ignorance that people have about this issue. You would think, given how much you hear about this issue, that people would know what the facts are. They don’t, for the most part. And guess what? Our politicians let them get away with it and the media doesn’t report it.

You noted that you’re one of the more privileged undocumented Americans. Since 2009, more than 2 million people of similar legal status have been deported by this administration, so I’m just curious: you came out in the New York Times as undocumented; you called up the INS and said, “Hey, how do I get deported?” Why do you think it hasn’t happened?

Well, one of my friends told me early on, “They’re not going to challenge you. You’re not what they’re looking for. You don’t fit their stereotype.” And for me, by the way, that’s been the biggest surprise. After I came out, I expected something to happen. What I did not expect was silence, from all corners: from the left and the right, for the most part.

I do recall a few petitions from conservatives calling for you to be deported, but that seems to have died down.

Yeah. It’s not like I’m hiding. And that’s the interesting thing. I spent all my teenage years and my 20s being scared, but once I let go of that fear it really just liberated me.

Do you have a plan if the INS comes knocking at your door?

Yeah, I have contingency plans. I have lawyers to call and all of that. I have plans, but apparently I’m not a priority. And should I be? I don’t think so. I am trying to simply contribute to this country which I call my home and I’m trying to use every possible skill I have as a writer, filmmaker – I’m just trying to be as effective and strategic as possible.

Speaking of strategic, that brings me back to your discussion of how the immigration reform movement needs to follow the LGBT activists’ example of focusing on culture before they try to change the politic, and I’m wondering if you think that’s a lesson that’s been learned from the election of Barack Obama. He was elected after the largest immigration reform rallies we’ve ever seen in this country. He says he’s an ally but he’s deported more people than anyone else. Does that speak to the failure of the immigration reform movement’s strategy up to that point?

I think we have politicized this issue to such an extent that we have been subjected to the kind of partisan politics that is characterized by dysfunction. I mean, let’s be honest: The president wants something to get done, the Democratic Senate passed an immigration reform bill, while the House, controlled by Republicans, didn’t want anything to do with it.

We also must remember that the president here is caught between a rock and a hard place. I know that, legislatively. But this president, who is a student of history, our president, my president, also understands that his legacy is on the line. Does the first minority president, the first African-American president, the first biracial president, does he want his legacy to be this? I hope not. I think not. But he has yet to prove to us that to him this is a personal thing.

Does he have time to change that legacy? In your film, you discuss how he implemented a sort of watered-down, executive version of the Dream Act, the deferred action program. I’m wondering, did that lead to tangible results? And is there anything else he could do that could turn his legacy around?

Of course, that deferred action program yielded positive results, like tens of thousands of young people – tides changed because of that. But that’s not permanent. It’s temporary. It’s an executive order that somebody can overturn. Again, that is still something: It’s the largest expansion of immigrant rights since Ronald Reagan passed amnesty in 1896. But let’s remember now, the same president who did that is responsible for an administration that has deported 2 million people in five years. And the New York Times just told us two days ago that two-thirds of those who got deported only committed minor infractions. I would like to know and to think that our president is trying his best, but on this issue I don’t think it’s been that personal or urgent for him.

I wanted to touch more on the Dream Act. Are you concerned that we’re creating sort of two tiers of immigrants: the ones who came here “through no fault of their own” and who want to go to college or join the military, and the others who maybe aren’t as deserving of our empathy?

Absolutely, there is concern. But I think we must remember that to the rest of America, they’re not making that kind of distinction. I have always said and will continue to say that the dreamers are only one part of the whole equation, but the dreamers are really important because they’re the bridge. They’re the ones who will say, “What about my mom? What about my uncle? This can’t just be about me.”

So the dreamers are important, and they’re a big part of the conversation right now, because they are a bridge to all those other conversations and other generations and we want to hit on that.

They’re the presentable face.

It’s not necessarily presentable; it’s accessible. It’s the most accessible place to start, but it doesn’t mean that we can’t talk about day laborers and migrant farmers. It doesn’t mean that we’re not going to talk about our parents and our grandparents and our uncles and our aunts. There isn’t a “good” immigrant versus “bad” immigrant here. Good or bad immigrant, we are still caught in the same broken system.

In the film, you talk about how you want “fair” and “humane” reform. I make you dictator for the day: What would your fair and humane immigration system look like?

Fair and humane reform would mean people like me would actually be given a chance to step out of the shadows, tell you who we are, tell you that we’ve paying taxes for all those years, that we’ve been educated, that we are speaking English and want to speak English, that we want to be a part of this society, and create a process for us to actually become American citizens. That’s why we called our campaign “Define American.” It’s not “Define Immigrant.” … For Asian and Latinos in this country, immigration is a personal issue.

And here is something really important: the role of allies. Immigration is not a Latino issue. Immigration is an American issue. We must engage white Americans and black Americans on this issue.

Why is it important to emphasize that immigrants want to “become American” and “want to speak English” as a prerequisite for their obtaining legal status in this country? Is there anything wrong with not wanting to assimilate into mainstream American culture or to learn English?

Well, but there’s nothing wrong with speaking English and speaking Spanish and speaking Tagalog all at once, right?

No, absolutely. I wish I could do that. I’m struggling with English.

The thing is, look, I think it’s important for Americans to know that we want to learn English and that we do speak English. And guess what? We do. Do you want to learn how to speak Spanish and Taglog? Do you want to learn how to speak Mandarin and Korean?

Sure. I have Duolingo on my phone now.

This is where I think the disconnect is. I actually think undocumented immigrants are showing Americans what it’s like to be Americans. What I mean by that is America is a fight. America is a struggle. America is something that is a privilege that people work for. It is not just something that you are given. It’s not just something you are born into. I remember when I was a kid I saw a film called “The American President.” I remember the last speech in the film, it was Michael Douglas as President Andrew Shepherd. “America,” he says, “is advanced citizenship. You need to want it really bad because it’s going to put up a fight.”