When David Einhorn gets gloomy, the stock market gets jumpy. In May 2008, the hedge fund investor warned that Lehman Brothers was headed for trouble. Five months later, Lehman declared bankruptcy and officially kicked off the worst financial crash since the Great Depression.

So when his current fund, Greenlight Capital, sent a letter to investors on April 22 warning that tech stocks were getting a little frothy, shock waves spread instantly.

“There is a clear consensus that we are witnessing our second tech bubble in 15 years,” wrote Einhorn. “What is uncertain is how much further the bubble can expand and what might pop it.”

The month of April offered some clear support for Einhorn’s views. Even as the Dow Jones Industrial Average pushed toward record highs, tech stocks embarked on a nerve-rackingly bumpy ride. The NASDAQ index is about 4 percent off its recent peak, and momentum seems to have drained right out of the previously thriving IPO scene. Just this week, Twitter investors hammered the high-profile social media company for a mildly disappointing earnings report.

And yet, even as cracks have started to show, venture capitalists and private equity investors are still funneling vast amounts of money into existing start-ups and early-stage companies. If anything, they’ve been opening the spigot up wider than ever. In the first quarter of 2014, VCs pumped a staggering $10 billion into tech. It’s been more than a decade since it was this easy to shake the money tree.

Pessimists are warning, however, that even the easy availability of capital can be seen as another warning sign. Companies are frantically loading up on cash now, because they know– everybody knows — that the business cycle will inevitably turn down. With the vast majority of these start-ups a long, long way from turning a profit, it’s only prudent to stash away as much cash as you can while the getting is still good. Because, like it or not, sooner or later, the bubble will pop.

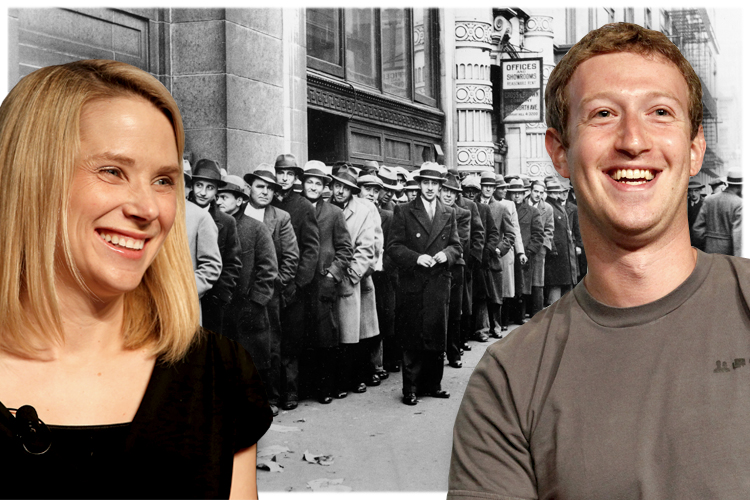

But if times are destined to get tough for even the current front-runners of the tech boom, then what does that mean for the rest of us? Because there’s a crucial difference between this boom and the last one that is not getting enough attention. Last time around, the average U.S. worker did pretty well: In the 1990s, the median wage rose steadily, while unemployment fell to its lowest point in generations. The economy as a whole added an incredible 21 million jobs. Point being: The prosperity was shared.

Compare that to the current tech boom. Wages have stagnated, and household income has fallen. Unemployment is still historically high and job growth has been tepid, at best. Even as all those billions of dollars of investor capital have poured into tech companies, workers — outside of a few regional hot spots like northern California — just aren’t reaping the kinds of benefits we would hope for in even a borderline healthy economy.

There’s good reason why everyone wants to know when the bubble is going to pop: It’s not just unlucky investors who keep their money in the stock market who will get burned. If workers aren’t doing well during a major stock market boom — propelled by astonishing tech sector growth — then how will they cope when the market goes bust?

The next turn of the business cycle is going to expose some ugly truths about how the current American economy is structured, and it’s going to poke some major holes in Silicon Valley’s pollyanna parade. Right now, it’s easy enough for Silicon Valley’s best and brightest to gab away about how they are changing the world by helping people learn how to trust each other and become more connected. But when push comes to shove, we’re going to discover that Silicon Valley will be far more obsessed with protecting the interests of its shareholders than in ensuring that the actual consumers of their services are treated as well as possible. If the boom already sucks for the average American, the bust is going to be much, much worse.

* * *

For a sense of how all this might play out, let’s take a closer look at one specific sector of the tech economy that has been getting more than its fair share of headlines in recent months: the so-called sharing economy. Companies like Airbnb, Lyft, TaskRabbit, Uber and even DogVacay offer a perfect snapshot of the contemporary Silicon Valley zeitgeist.

Their rhetoric is world-changing and socially uplifting — the current cover story in Wired magazine boasts the headline: “How Airbnb and Lyft Finally Got Americans to Trust Each Other.” Their profits are nonexistent, but their ability to raise capital is fantastic: In just the last month, reports Jeremiah Owyang, an analyst who specializes in the sharing economy, a handful of companies in the “collaborative economy” raised a remarkable $852 million.

In truth, these companies offer the perfect illustration of how current economic trends are not working for the average American. Their business models are explicitly predicated on helping people who are economically struggling. The sharing economy, by and large, provides platforms for people to squeeze a few extra dollars on the side to help pay the bills. The fact that, as a consequence, we are having more meaningful relationships with strangers is an accidental byproduct. The real driver here — as New York magazine’s Kevin Roose captured perfectly in his reaction to Wired’s cover story — is desperation, not a craving for more trust. We’re sharing our belongings — or to be more precise, offering short-term rentals on them — because we have been forced to do so by our economic circumstances.

There is no question that sharing-economy companies have created effective platforms for more effective distribution and allocation of resources. The Internet makes it insanely easy to share, or sublet, or outsource — whatever you want to call it. But as Sarah Kessler demonstrated in an article for Fast Company — aptly titled “Pixeled and Dimed” — this doesn’t mean that living off the sharing economy is easy. Quite the contrary: It turns out to be quite difficult to stitch together gigs and short-term rentals into a decent living. It’s exhausting and demeaning.

In terms of actual compensation, it’s pretty clear that the “gig economy” facilitated by TaskRabbit, and FancyHands, and Amazon’s Mechanical Turk are exerting downward pressure on wages, by widening the pool of potential job applicants for any given task to essentially everyone with Internet access. When we’re all competing for the opportunity to open someone’s mail or mow their lawn or pick up their groceries, the lowest bid tends to win. The sharing economy doesn’t just efficiently exploit our possessions; it ruthlessly exploits our labor.

The disjunction between how hard it is to make money as a consumer of the sharing economy, compared to the potential windfall from owning the platforms that facilitate it, is ludicrously massive. Airbnb just raised $450 million, giving the company a market valuation of $10 billion. Is there any better snapshot of inequality in America then the fact that a platform that enables you to sublet your spare bedroom and help you make your rent is worth $10 billion? Yes, the users are happy to get what assistance they can in making end’s meet. But when IPO day comes along, the owners of the platform will transform into instant card-carrying members of the 1 percent.

And therein lies the rub: Once IPO day does arrive, or some larger publicly traded company comes around to gobble you up, the incentives that guide management behavior change significantly. Maximizing shareholder value becomes paramount. And that’s a very big deal in a downturn.

As my former colleague Scott Rosenberg wrote this week, in a blog post titled “Lies Our Bubbles Taught Us,” it is extremely unwise to accept at face value the ubiquitous start-up entrepreneur claim that “we will always put our users first.”

Many startup founders are passionate about their dedication to their users, in what is really Silicon Valley’s modern twist on the age-old adage that “the customer always comes first.” One of the side-effects of a bubble is that small companies can defer the messy business of extracting cash profits from customers and devote their energy to pampering users. Hooray! That makes life good for everyone for a while.

The trouble arises when founders forget that there is a sharp and usually irreconcilable conflict between “putting the user first” and delivering profits to investors. The best companies find creative ways to delay this reckoning, but no one escapes it.

As we wait for the current bubble to pop, it is instructive to apply Rosenberg’s insight to the business models of the sharing economy. The great genius of Airbnb and Lyft and all the rest is that they have figured out ways to avoid bearing the huge costs that afflict the industries they are “disrupting.” Airbnb owns no hotels, Lyft owns no cars, the people who get temp work through TaskRabbit aren’t actually employees of TaskRabbit. There’s also plenty of skimping on the consumer protections that existing industries are required to offer, by law.

Right now, sharing economy companies are scrambling to address consumer protection concerns and other regulatory constraints. (Uber’s recent institution of a $1 “safety fee” on its rides explicitly recognized that the task of vetting drivers and accounting for insurance adds expenses to the bottom line.) But reconciling those accounts — taking care of users and generating a real profit — will become much harder, and perhaps even impossible, when the economic tide finally turns.

But maybe the news won’t be all bad. Because here’s the silver lining underneath the next bust. The sharing economy, like Wal-Mart and McDonald’s, may turn out to be more-or-less recession-proof. A business model based on helping people squeeze extra pennies out of freelance jobs or more efficiently maximize income from one’s existing possessions is well positioned to thrive in a down economy. Come to think of it, Silicon Valley may have solved the business cycle. A business model that works when workers are getting rough treatment in a reasonably functioning economy will really hit its stride when everything goes to hell, again.

Which just seems to prove that — boom or bust — Silicon Valley’s new robber barons are bound to win either way.