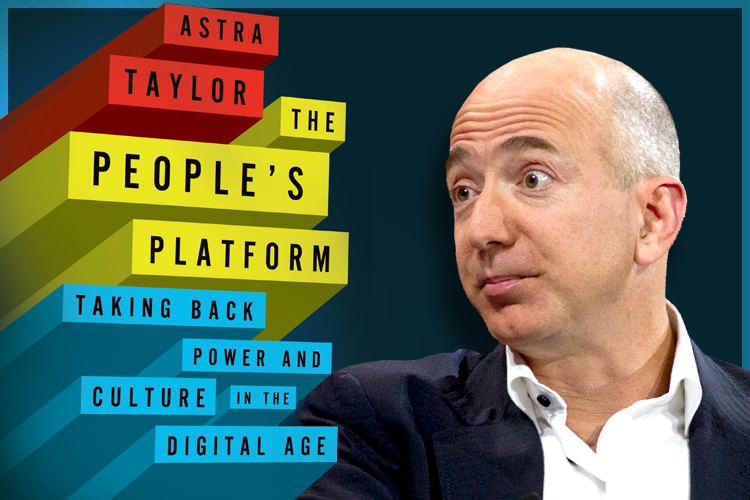

Astra Taylor, a Canadian-born documentary filmmaker who was involved in the Occupy Wall Street movement, has just released “The People’s Platform: Taking Back Power and Culture in the Digital Age.” Harder-edged politically than many Internet books, “The People’s Platform” looks at questions around gender, indie rock, copyright, the media, the environment and advertising. “The digital economy exhibits a surprising tendency toward monopoly,” she writes in her preface. “Networked technologies do not resolve the contradictions between art and commerce, but rather make commercialism less visible and more pervasive.”

An admirer of Slovenian philosopher Slavoj Zizek (and director of a 2005 documentary about him), she frames the current crisis with European cultural theory. She’s also recently been playing accordion in her husband Jeff Mangum’s band, the recently revived Neutral Milk Hotel.

“The scariest book I’ve read in a while is almost the most exhilarating,” author Rebecca Solnit writes on the jacket; media critic Douglas Rushkoff calls it “perhaps the most important book about the digital age so far this century.”

We spoke to Taylor, who lives in upstate New York, during her visit to New York City.

So there have been a number of cautionary books about the Internet already, some of them quite good. What story did you think that we weren’t hearing about the effects of technology?

I definitely thought there was something missing, a critique or an analysis that really emphasized the economic underpinnings of this technological transformation; what I thought was missing, to use the academic phase, was a political economy of new media. And in that sense there wasn’t a book written for a popular audience that was a left critique of the Internet. Because there was Nicholas Carr’s good book “The Shallows,” which I actually quite liked. And Jaron Lanier’s more eccentric and interesting books. But they’re not leftist manifestos.

I felt like there’s something missing from those books too, about the continuation of not just economic hierarchies, which of course I’m paying attention to, because that’s what political economy is all about, but also social hierarchies. And both of them are very concerned with the way that creators have been demoted, and the devaluation of literature, and Jaron Lanier writes about the hive mind. But for me, as a woman, you have to cheer the toppling of the canon and hierarchies because otherwise there’d be no space for you. And to me, being a progressive is wanting progress, wanting change. But I want the change to be toward something more just, more inclusive, more diverse. And so I do think there’s something about being a leftist but also just being a feminist that puts a different twist on this.

Your book is especially good on digital utopians. Can you remind us of some of the outlandish claims made for the Internet when it was new? I mean, those people are obviously still out there and still vocal, but it’s interesting to look back at all the stuff the Internet was supposed to deliver to us — democratizing culture for instance was one of them, and making a better or “more connected” world. What did they tell us we’re going to get?

The Internet was supposed to either change everything for the better or for the worse; it depends who you were listening to. But certainly a more connected world, a cultural sphere that was inclusive, that made space for everyone. That didn’t require that you ask anyone for permission. Where you could do it on your own. And it was also going to transform politics. I mean, along with participating in the culture, it was also going to be easier to change the culture by finding people of like mind and joining with them. Or finding out the truth. And being a citizen journalist and revealing it. And doing a better job than the mainstream media, which has disappointed us for so many years.

So all of these prophecies were made very heartily by smart people for a very long time. And it’s not that it was just pundits or people who wrote these books for a living. You’d go to a conference on media reform and talk about the condition, the lack of reporting on the financial crisis or something, and there’d always be a question from the audience: Well, what about the Internet? Now we can tell the truth. So it wasn’t just that there was this class of techno boosters who were misleading us, there was a sense, and I think a valid sense, that technology was really powerful and was going to change things. And in many ways it has. I mean, that was something that I really struggled with in the book, was to recognize how awesome the Internet is, and how different it is than the old broadcast model. But that doesn’t mean that we just have to be put into this gee-whiz stupor and stay there. And I think people are snapping out of it. We almost risk at this moment a falling into a kind of disappointment or disillusionment because overnight it went from being this politically enabling, Arab Spring-empowering medium, to being a giant government spy apparatus. I feel like it’s kind of both and I feel like it’s time to grow up a bit and have a different conversation.

Let’s go back to hierarchy. Originally, when the Internet broke in the ’90s, it came a few years after what we were calling “alternative culture.” And it seemed that like Nirvana and the rest of alt-rock or indie film, it was allowing us to get outside the mainstream media: It could be an extension of alternative culture. What happened from there? Did that end up coming true, and what happened instead?

Well, what exactly happened, I’m not sure. But certainly there’s been a blurring of inside and outside. And the clear boundaries that might have defined alternative culture in the ’80s and ’90s… when it was obvious who the mainstream guys were, and then you had your underground and independent labels and zines, that’s gotten more muddled because all of the cultural exchange we do is on these corporate platforms. And there’s been this embrace even in subcultures of the rhetoric and logic of branding. Which is something I go after in the book, because I personally find that to be really repellent and not for me a way of understanding yourself as a human being.

I mean the reason branding developed, when you stopped buying your oats from a big bin from the local shopkeeper, but they were being mass produced, so they put a dude’s face on the oats. It’s a fake human they put on a box for you to buy. So if you’re a real human, you don’t need a brand. But it is symptomatic of the shifting landscape; it’s almost like, as much as alternative culture has suffused the mainstream, the mainstream and commercial culture has suffused the underground now.

As you say, the lines used to be drawn a lot more clearly and the era of “corporate rock sucks!” was very different than a period when, now, even indie bands are embracing branding and various kinds of merchandising schemes.

Yeah, but I think the thing is… I quote G. K. Chesterton and he basically says art, like morality, consists of drawing a line. So to me, you do have to. I’m not saying things are blurry and that we should embrace the blur or embrace the muddle. I think we actually need to look at the conditions that are giving rise to that muddle.

So there’s a lot of bemoaning the fact that younger people in younger bands have given up on the idea of selling out. And I look at the way that basically if you’re operating in a system where there’s less and less support for the art in itself, then what happens is advertisers step in and fill the gap. And so this is one area where I challenge my friends who have embraced the mantle of free culture. And I see that they mean free as in information, but it also in practice means free as in price. And if you want the uninhibited exchange of information online and you’re not paying for things, then what happens is, marketers are more than happy to fill the breach, because they want their products to spread. They don’t want scarcity, they want abundance, in the sense that they want their messages to go viral.

So part of it is the decline of the buying and selling of records and the move toward this kinda viral, digital model. But one of my first impulses for writing this book was actually going to one of these social media, Web 2.0, rah rah rah, conferences. And it was like, isn’t it great we can all make videos and we can all participate, and won’t it be cool when our videos get picked up and sponsored by Chipotle or something. And I was sitting there, and I was like, I’m sorry, I didn’t become an independent filmmaker to make an ad.

Right. There is no anxiety among some indie people, whatever their field, about having connections to say, corporate fast food.

See, but I think there is anxiety. I don’t believe that everybody’s given in. And I think that we hear about the people that say yes. And we don’t hear about the people who say no. And we get a bunch of skewed data. Because it’s not like you hear about the people who say no. You don’t hear about the people who say, “Fuck off, my song was made to dance to, my song was made to eat dinner to, my song was made to pick up my kid from school to, but it wasn’t made to sell your air freshener with.”

Those people, I think they do still exist. And I think that we have to see selling out as a kind of structural condition. Actually, I just wrote a little thing for the Guardian about this. It’s basically like, if you look at the architecture of social media too, Google changed its terms of service, kind of aligning it more with Facebook, where they can use your likeness in an advertisement. Facebook calls them social ads, and Google calls them shared endorsements or something. So if you glance at something on the Internet, then suddenly your face, your name, your likeness can be used to promote that product to people who aren’t you, then there’s this question, you’ve been an ad, you’ve been an ad your whole life, so the question of your personal purity is very different in that context than one where you’ve been able to protect that. Or you just haven’t been sucked into this whole system of advertising. So, I think we’re changing the status quo, and that’s not the kids’ fault, that’s the fault of grownups who work at these companies and are making the salaries, and making the decisions, and designing these new revenue mechanisms. I blame the grownups.

So I think, selling out: Often it’s about the choices that individuals make and we scrutinize people. While I personally do have lines that I care about and that I don’t want to cross, I can see that they’re subjective and they’re what I’m comfortable with. But I would like us to have less judgment on individuals and more judgment on larger society. Because the thing is, we as a society have chosen not to fund things through the public purse and instead we, say, have Purina brand our doggie park. Or we name the auditorium for Bank of America. So we’re making these choices all together and I feel like sometimes we just, we get really disoriented when we focus on one person or one band’s decision.

You’re saying it’s a larger structural and economic issue. I wonder how your work as a documentary filmmaker helped inspire or shape the book?

As a documentary filmmaker, I was thinking about how to operate. I kind of had this sense when “Examined Life” came out that it was possibly even more of a special experience because the film was actually blown up to 35mm and shipped around theaters and it was kinda before this shift to HD digital distribution, which has actually hurt a lot of independent art houses, because the projectors are so expensive, and they’re also proprietary.

So the shift has hardly been one where theaters are saving all this money and making a killing, which is sort of the digital promise. But they’re obligated to the distributors and they’ve got this insanely expensive equipment that may need to be upgraded in a couple years. So one was just me thinking about what is my work gonna look like in a few years, if I made another film, how would it go out in the world, would I bother with all of this, or would I just go directly to the audience and do it myself? And so I just started thinking more and more about it.

I was someone who was kind of raised on the media criticism of Noam Chomsky and Robert McChesney. I remember being 13 or 14 and watching the film “Manufacturing Consent.” And obviously that film kind of inspired me to make my philosophy documentaries, “Zizek!” and “Examined Life.” It’s kind of a combination of “Manufacturing Consent” and Agnès Varda; they got in my head and made me think that I too could make weird, nerdy movies. But that kind of media criticism was nowhere to be found, so I’d go to these conferences or read these books about the Internet and they basically had this inchoate sense that the old system sucked… It was almost like they felt it sucked because they weren’t the elites. It was almost like a right-wing populism. Like, “Down with the cultural elites, down with the journalists, down with the professionals.”

That sentiment is alive and well.

Yeah, exactly. Instead of down with the Wall Street guys who were wringing 20 to 30% profits from the newspapers and making them publish crapola. So the political economy, the Chomskyian or McChesneyan argument was about the corporate elite behind the scenes, and the Web 2.0 argument was about the cultural elite and so…

There seems a missing piece.

Exactly. There’s a missing piece, and what had motivated me to be an independent media maker and dabble in journalism and make these films was kind of a commitment to an independent alternative to that. It wasn’t that I was against journalists; it was that I was against a system that was ultimately profit-driven and corporatized. Which is ironic given that my book is now published with a mainstream publisher.

Well, there’s usually not any other way to reach a large audience, so I won’t hold that against you.

Well my thing was that I really wanted to work with the two women who run the imprint, who are editors of books I really admire, and I really wanted to become a better writer.

But yeah, definitely being a documentary filmmaker influenced my analysis and was also, I would be struck too, reading books by corporate consultants or by professors, whoever the sort of rah, rah, rah tech triumphalists of the day were, and they would be talking about cultural shifts and this and that but they never really talked to an artist before, the people trying to make their livings… I just thought there was something valuable to bring to the table, as someone trying to make it in the world making independent films. And then as I got more and more involved in Occupy, I felt like these tech boosters, they love the Arab Spring and they love the Twitter revolution in Iran, but the minute there was something in the United States, they didn’t have anything to say about it. It was just crickets.

You bring a lot of different fields together in your book. You’re a filmmaker obviously and you have a concern about that sphere, you write about indie rock, and indie culture, but you also have a lot about journalism. I wonder why that seemed important and part of the same story?

In a way, I wouldn’t mind being a journalist, except it’s just too much fucking work. The few times I’ve done it, I’ve just been struck by how necessary and hard it is. I think I quote Tom Frank where he said, “The point wasn’t to get rid of journalism but to do the job better.” I empathize with all of the criticisms of the mainstream media, and the disappointment in the idealism around the idea that we could do it better ourselves and be citizen journalists. But then when you actually try to go and report a story, it’s just an incredible amount of work, and if you are messing with the powers that be, looking at something they don’t want you to look at, they will do everything they can to stop you. So I think it’s just an incredibly important part of the story because, according to a statistic that I read recently, actual, professional, paid journalists, the number of them has shrunk between 40 and 50 percent since 1980, so basically since I was born. And there are 100 million more people living in this country so… and we know that, we should know that this is not something to cheer. Because who wants there to be no journalists? Corporations who are polluting the environment. Or politicians who are taking selfies.

I mean, you write about that quite well in your section on the BP oil spill. And Doug Rushkoff and Robert McChesney have both documented as the number of journalists have gone down, the number of PR people and spinmeisters has increased, so the ratio has gone all out of whack. You have a lot more people trying to spin the news than to report it.

And some people estimate up to 80 percent of what actually makes it into the news is ultimately brought to the table by PR folks. I felt with that chapter that in a way the subject had been done to death. And it’s hard to add anything new, but it’s something that I feel is very important. Journalism is important to the health of our democracy. All the clichés are true. And the thing is that the story is told too often as though the Internet came and changed everything and hurt newspapers and created this new model of clickbait. And it’s really important to emphasize that it’s actually about continuity because it was the conglomeration of the newspaper industry, the fact that this handful of companies were buying newspapers up and maximizing their profits, it was such an amazingly profitable industry for awhile, 20 percent, 30 percent profits, I mean amazing. The envy of the world. And as they were squeezing those profits, they were basically devising the techniques these digital first publications now have to totally cave in to. Making things short and sensational, shallow and digestible and all this. So the continuity needs to be emphasized, and the fact that ultimately it’s about the business model, it’s not about the medium. It’s not pixels or the page, it’s really trying to make money from something that is ultimately a public good. It’s really hard.

It’s harder every day. That’s for sure. Something else that’s interesting: Americans on both sides of the aisle politically are outraged by NSA surveillance and other kinds of government spying. I wonder if we should be more worried about tech corporations, many of whom are run by libertarians who emphasize individual liberties, being left alone, and so on. The fact is, these companies are often keeping their eyes on us as well, and selling/trading information about us all the time.

Yeah, I think we have to recognize the way corporate and government surveillance are intertwined and really hard to separate. I think the NSA debates have ultimately been so beneficial. I really admire Snowden and Glenn Greenwald and Laura Poitras, who I actually talk about in the book, before all this really happened. She’s one of my heroes, and was well before this whole debate. I mean she was one of my heroes because of “My Country, My Country,” and “The Oath.” I just think she’s a remarkable filmmaker. So she’s been in my pantheon of heroes.

But I try to shift the conversation a bit away from the framework of the big bad government. Even though that’s true. I’m not denying it at all. As an activist I have to be totally outraged and it totally fits into the history of COINTELPRO and sabotage, and it sucks. But I don’t want to give in to the libertarian logic of our time, which kind of throws its hands up and says all institutions are corrupt. States are corrupt. Schools are corrupt and newspapers are corrupt and it’s all corrupt. I’m trying to articulate a more nuanced view.

So if I could do it again, if that stuff hadn’t broken toward the end of me finishing the book, I would try to insert some awareness to structural inequality into the surveillance debate. I’m kind of just riffing right now, but the debate is framed as government spying on us, but the hero figures are these white male hacker dudes. And they’re empowered by cryptography and they’re going to make cool software products that will help us be invisible. And I mean, more power to them. We need them, and I’m happy that… if people are more conscientious about encryption, I think that’s fantastic.

But ultimately it’s about, who is surveilled in this world? Well, it’s mostly minorities and people of color. It’s Muslim Americans, as we’ve seen. Or it’s poor people on the job who are being monitored and tracked. There are implications, the way that data brokers create these dossiers and potentially employ them to discriminate in terms of pricing or credit opportunities. So I’m interested in the way that these…that we need to look at surveillance as not just a First Amendment and Fourth Amendment issue but actually as a Fourteenth Amendment, which is about equal rights, and as more of an economic justice issue and not as the civil liberties frame that it’s thrust in. So that’s something… I haven’t fully explored that thought.

The Internet evolved, in this country, in a post-Reagan, post-Cold War, neoliberal world where we’d given up on the idea of the public; markets and the private sphere were really triumphant. So it evolved in a certain direction because of that larger structure around it. But Europe and Canada, maybe Japan, and elsewhere have had a slightly different tradition. I wonder if we see the Internet taking different shapes in those places. Or does the fact that we’re globalized mean that this neoliberal, Washington Consensus thinking has shaped it almost entirely?

One thing I wanted to do was to shift the debate back to the United States, because I think some of the metaphors and analogies we were using were misleading. So all the enthusiasm around the Arab Spring, to go back to that. We’re modeling what the Internet can do, what social media can do, but based on a political context that was so different from ours.

Excellent point.

Because the United States is messed up but it’s not a dictatorship. It’s certainly not the same. And these are questions that I get as an activist all the time. Again, it’s not just a few pundits. Well, look at the Arab Spring; you have social media, how does that change everything for you as an organizer? So I wanted to shift the frame and say, this is the United States, maybe we need to look at corporate power. Just some fantasy of an authoritarian control freak… That power works in different ways here, it is invisible and networked, and that it’s a context in which we are all invited to speak and come in to participate, but profits are still flowing to the usual suspects. We just saw, I think it was this week, Google and Apple are now the top two corporations in terms of market capitalization. So there’s still wealth and power but we’re not living in Egypt. We have to think about where we are. That’s why I think it’s so interesting that the pundits didn’t have much to say about Occupy.

Well, I think what people have trouble understanding is that the Internet could have a liberating effect in say, China or a Middle Eastern theocracy. But could have a different kind of effect on the American middle class. That kind of nuance, that there can be good effects here and frustrating effects there, hasn’t really come into the debate on the Internet very well.

Yeah. Or that there can just be good and bad effects here. That these two things can coexist and to critique Google isn’t to critique the Internet or to hate technology. I think your question about other countries, it’s an interesting one today because Brazil just passed this new quote-unquote Internet constitution. And it enshrines protections for free speech and some privacy protections and net neutrality, and it’s far from perfect, and I’m sure people will criticize it and dissect it. But it’s an example of another country taking charge and that follows victories for net neutrality in Chile and the European Union and so, and of course Europe has much stronger baseline privacy laws.

Here in the U.S. we don’t have basic, cross-sector privacy laws that can be applied to new technologies, to each sector on its own. So the new toy comes up, there’s nothing to fall back on. So I think there are… those laws are strong privacy regulations that will shape the development of the Internet in other countries. Because right now, the United States is pushing an Internet economy or digital economy that is based on advertising. It’s a business model based on surveillance. There are other ways of putting some sort of friction into the economy and so yeah, I think other countries. I think there’s also talk in France about, I don’t know if it’s a Google tax or if they called it something else, but taxing devices and gadgets and using that to fund culture. That’s something that’s happened before. Or in Britain, the BBC was funded through a tax on television sets or antennae or whatever it was.

Right. Well in Europe and Britain there’s much more of a sense of culture as a public good, a sense that culture needs to be funded, and it’s a really different tradition than what we have here. Our tradition is a frontier model, I guess.

Right, but that’s being exported, though. Our models are being exported. But I think there is still a chance to find other ways of doing things and we see ourselves as the center of innovation and it would be, once in a while, we should be open to the fact that someone else might be doing something right.

Let’s close by looking forward for a second. Your chapter called “Drawing a Line” and the conclusion to your book, you talk about what you hope can happen in the future. You describe the cultural crisis, the democratic crisis… What would you like to see happen in the next few decades to bring things back into balance?

I would like to see so many things. (Laughs) It’s hard to know where to start. The issues I’m raising can’t be considered in a vacuum, disconnected from larger economic trends. When you brought up the American middle class, I was just at the MSNBC offices, the American middle class is no longer the richest in the world.

That New York Times story from the other day.

“The Canadians are beating us!”

And you’re secretly Canadian as I recall.

I am so secretly… I mean, this book really reveals my secret Canadian-ness.

It gives the lie to this idea that there is only participatory culture now because of the Internet. No, people made things before they were on Facebook all the time. It’s not like we were all sitting there, lost. Okay: The issue of the middle class. I don’t see this book, this intervention, as separate from my work with Occupy Wall Street. I recognize that they’re intertwined and these issues we’re bringing up about the rich getting richer online, and wealth and power flowing to this handful of info monopolies, echoes the broader economy and you can’t separate it.

Right. And as Thomas Piketty has documented recently, that’s a problem that is not going away, and it’s not getting any better, even though we’re talking about it way more than we did before Occupy. We have terms for it like “the 1 percent” and “income inequality,” and we have the numbers to show what’s happening, but it’s not like it’s reversing itself, just because we’re paying attention to it.

Exactly. And I think it’s important to look at these platforms in these contexts. So okay, you may not feel like you’re being exploited by Facebook, you’re not a laborer. I talk about how some people have employed a feudal metaphor for these services, but value is being extracted from us, value is being extracted from areas of life that were once unprofitable, like conversing with your friends.

If we live in an increasingly networked landscape then it could be that we’re tracked as we move from space to space, park our car, turn our thermostat up or down. All these could potentially be sources of value extraction. So how is this digital economy basically helping or augmenting, I’m not saying causing, but flowing into this larger trend toward inequality?

And I think that is a fundamental challenge to this idea as a democratizing force.

That said, any campaign we mount to make the world more equal and just will have to use technology. And we will have to be savvy, and we will have to spread our messages through whatever channels we can access. But we will have to do something far more pointed and strategic than just spread the word online. We’ve seen the limits of that; we’ve seen that while social media can really help with spectacle it doesn’t really help us wrap our mind around the problem of building power and challenging power, so that’s why I wanted to put that word back in there in the subtitle. It’s not just about conversation and making your opinion known and “liking.” It’s ultimately about power. And that’s something that the left is really afraid of, I think, and shied away from over the years. What I’m trying to show is that despite all their heady rhetoric about democratization and sharing, that ultimately power is what’s being hoarded.