If you were expecting a fair bit of Christian banner-waving in the wake of the Supreme Court’s recent decision to allow legislative prayer in public meetings, you likely weren’t disappointed: major Christian political groups like Faith and Action were jubilant about the decision, as were other Christian leaders acting on behalf of various religious liberty organizations across the Web. Though the decision was not specifically Christian – it allows for any sectarian prayer to be practiced at public meetings, meaning that all who seek to pray on behalf of their particular tradition should theoretically be given the opportunity to do so – the fact that the United States is roughly 70 percent Christian (at denser concentrations in some places) means that the impacts will likely have broadly Christian implications.

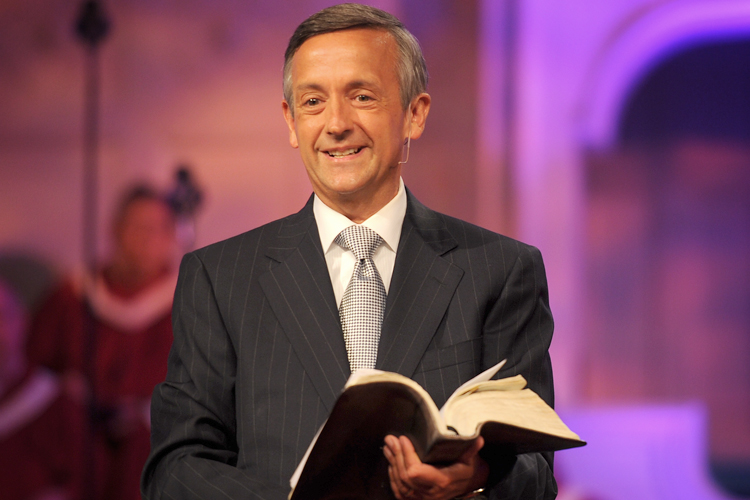

Nonetheless, the favorable decision wasn’t latitude enough for some Christians. Writing for Fox News, pastor Robert Jeffress supposed the decision did not reflect a sufficient understanding of prayer, and argued:

The Supreme Court should have clarified on Monday the original intent of the First Amendment. If the framers’ purpose had been to prevent hurt feelings among its citizens, they could have easily used the words “entanglement” or “endorsement.” Instead, they wisely mandated that as long as Congress does not coerce citizens to worship in a state-sponsored church government has no business restricting or regulating the free exercise of religion anywhere—including in the public square.

Arguments about the language of the Constitution can likely be carried out with greater historical and legal sensitivity, but the point remains that for some Christian leaders, the boost resulted not in a gracious nod of gratitude, but in another round of poor sportsmanship. The push to be demonstrably insensitive to “hurt feelings” – by which Jeffress means the sense of isolation members of religious minorities or the non-religious could come away with after sitting through a distinctly Christian prayer – seems disingenuous and macho. The reality is that in a democratic setting, a sense of equality and goodwill is necessary, and chalking up a sense of isolation to “hurt feelings” is intentionally obtuse and condescending.

A body of research concerning religious priming, or the cognitive effects of exposure to religious words or cues, has demonstrated that being placed into a religious frame of mind can have pointed effects on the religious and those with particular personality types. It can, for instance, encourage pro-social behaviors in anonymous games; yet it can also potentially aggravate racial prejudice as well as submission and conformity. And yes: Religious priming has been found to influence voting as well. That religious people should vote with the ethics of their traditions is no knock against prayer in public nor coherent religious practice; rather, the point I mean to demonstrate is that religious words do not go “in one ear and out the other”; they’re powerful terms, and they genuinely affect people. If they can encourage the religious and the deferential to subtly alter their behavior, then they can certainly have a marked effect on the self-perception of religious “outsiders,” and a sense of distance and unease has no place in robust democratic discourse.

Which doesn’t mean that prayer has no place in public meetings, but rather that Christian leaders, who in the United States operate in a politically privileged majority, should take special care to practice public prayer with the utmost sensitivity. This means absolutely doing away with the attitude Jeffress promotes, which equates the low-order concern of ruffled feelings with the paramount concern of democratic participation. Why?

There are multiple principled Christian reasons, among them being directives from Jesus not to pray in order to fashion an image or create a particular personal or political aesthetic, which given the preponderance of Christianist political theater in the United States seems an immediate risk. But short of knowing the hearts of men those sorts of charges are hard to stick. The principle that can be heavily evinced has to do with how religious majorities should conduct themselves when they have, as it were, a bully pulpit.

Global Christians likely understand very well what the far end of that spectrum is like. The women kidnapped in Nigeria by Boko Haram surely understand it, as do the many Nigerian Christians whose lives were threatened by Boko Haram leader Imam Abubakar Shekau’s self-stated goal to “soak the ground of Nigeria with Christian blood.” The remaining Christians of Raqqa, Syria, who are subjected to Christian-specific taxation, death threats and now the shadow of public crucifixions likely have a very keen sense of what political systems bent on religious domination are capable of. It is in a mind-set of solidarity with those brothers and sisters in Christ that I sincerely urge Christian leaders who adopt Jeffress’ gung-ho attitude about enforcing public Christian prayer in democratic meetings to reconsider their approach.

It is not that having to sit through a prayer that excludes your tradition is in any sense equivalent with enduring the intense persecution Nigerian and Syrian Christians are currently experiencing, but rather that not even the image of domination of minority traditions by a majority should be allowed to persist in a democratic setting. Reasoning in a Christian frame is absolutely the call for Christians, but with a majority status comes special responsibility for the protection of minorities within that system, lest we climb unknowingly onto the far end of the same spectrum of religious domination currently incarnated at its most extreme in Nigeria and Syria. Why not, for example, pray at the end of a meeting, after all contributions have been made, allowing those who do not wish to participate in the prayer to filter out? Alternatively, Christians wishing to pray over the political process itself could meet in advance of a gathering or schedule regular prayer meetings aimed at strengthening their judgment and wisdom.

However it’s done, inhabiting a majority position isn’t something to take lightly. In many senses it’s an exemplary role, and Christian leaders facing contemporary religious politics could benefit from performing the role with an eye for demonstrating the pluralism we have – and better versions we might create.