Since 1989, when Amy Tan published "The Joy Luck Club," the multigenerational novel portraying the lives of Chinese-American women has become a thriving subgenre of its own. Typically, these are tales of globe-spanning blood ties stretched and strained by war, tragedy, dislocation and cultural bewilderment. There are the moms, who have often endured unspeakable loss in a far-off country, and the daughters, whose worries and victories are the relatable stuff of everyday American bourgeois life, immigrant version.

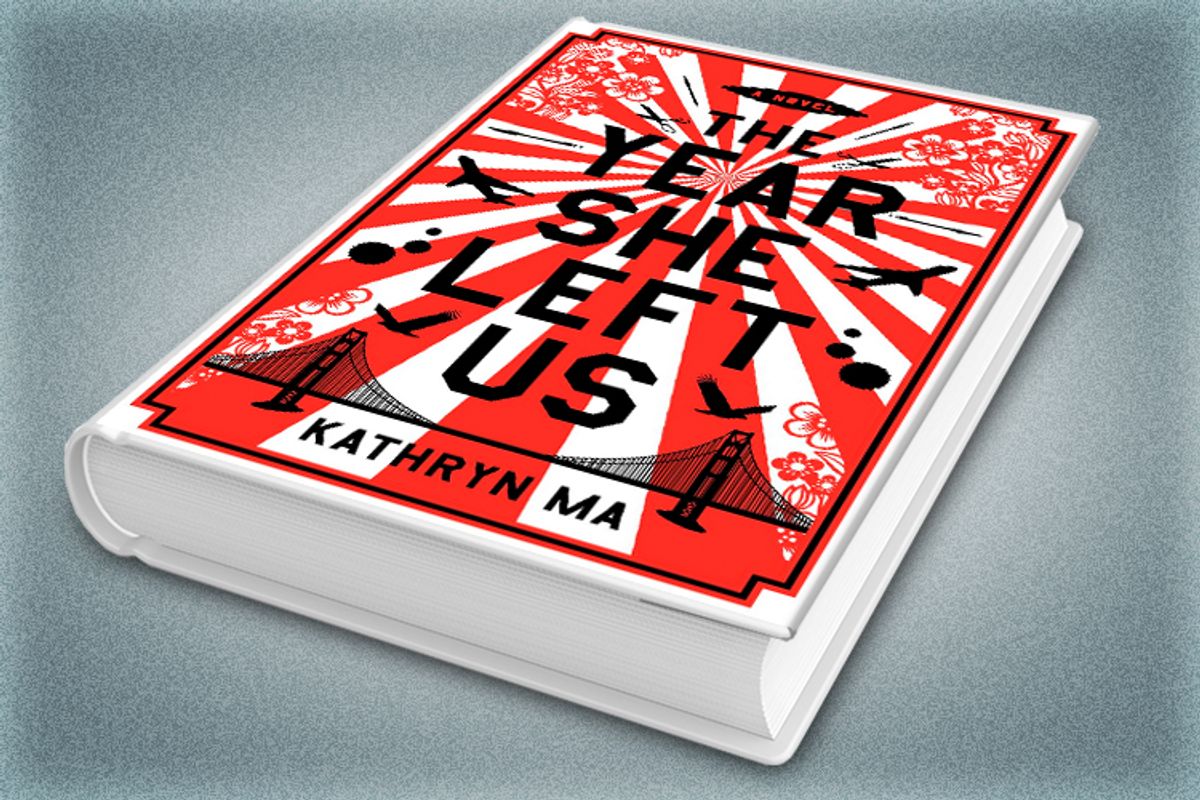

"The Year She Left Us," Kathryn Ma's debut novel, has a fond and playful relationship with the storytelling that "The Joy Luck Club" pioneered, even if it's written in the early 21st-century style of wry, satirical, meticulously observed domestic realism exemplified by Jonathan Franzen. It's got three generations of women, ranging from Gran, who came to the U.S. from Shanghai in her late teens, to Ari, now 19 herself. Ari's full name is Ariadne Bettina Yun-Li Rose Kong, which should give you a sense of how overdetermined her identity has been from the very start. As the novel begins, Ari is melting down under the emotional pressure imposed on her by the hovering attentions of not one but three "mothers."

Ari has three mothers and no father because she was adopted, a member of what she describes as "The Lost Daughters of China. The Unwanted. The Inconvenient, the Unhappy Outcome of the One Child Policy. Rescued is how my mother, Charlie, sometimes put it. I have a better word. Salvaged." As an infant, Ari was found on the steps of a department store in Kunming, in "not a basket, actually, but a plastic tub -- this wasn't Moses in the bullrushes or some other romantic shit." Unlike most American families who adopt Chinese girls, Ari's mom, Charlie, isn't white and she isn't married. Ari has been raised by Charlie, an idealistic public defender; Les, her sister, a competitive Superior Court judge; and Gran, their mother, a former belle of Shanghai society who has burned through two rich husbands and whose two enduring passions are driving expensive cars and Bryn Mawr college.

Charlie, Les and the sublimely unsentimental and quotable Gran ("You always hope for the best," she tells Charlie. "You didn't get that from me") level all their considerable powers on the task of raising Ari right: a playgroup with other "Whackadoodles" (a nickname for Western-adopted Chinese daughters), exquisitely calibrated discussions of her feelings and a trip to China when Ari was 12, intended to acquaint her with her "heritage." (Gran's response to that idea: "We made you Americans. All that 'Roots' stuff is nonsense.") But the girl has a shard lodged in her heart. Ari rages at being called "lucky" and prizes the few relationships she has with people willing to use "the A word" -- not "adopted" but "abandoned." On a second trip to China she suffers a breakdown and ends up chopping off one of her pinky fingers at the knuckle.

There's much to enjoy in "The Year She Left Us," including a lively sketch of the inner workings of San Francisco's legal community. A subplot involves jockeying over who will hear a case in which a Chinese-American laborer is charged with a hate crime for beating his racist boss. Chapters told in the first person, by Ari and Gran, alternate with third-person chapters describing the lives of Charlie and Les, who's conducting a clandestine affair with a high-powered, married African-American corporate lawyer. But the Charlie and Les chapters, though they buzz pleasantly with the believable business of adult life, inevitably feel a bit thin when contrasted with the first-person chapters.

It's Ari's voice that sets this novel on fire. She seethes and broods with a furious wit that refuses to spare even itself. Describing the orphanage where she spent her first months, she notes, "We were all given Director Zhu's surname, a favorite practice of slaveholders in the South. I mean the American South, not southern Yunnan, and God, how offensive, comparing myself to a slave. It's hard to keep track of one legacy over another when you don't know which country's history you belong to."

The magnetism exerted by Ari's chapters is all the more impressive because for much of the book, the character's misery seems to float free of her circumstances. It's not until the closing pages that she can bear to baldly lay out the "old whispers" that haunt her: "Who were my mother and father? Did they ever think about me? Were they sorry for what they did? If they had held me in their arms for another day, a week, a month, a year, would they have changed their minds and kept me?" An equally pertinent question might be: Why is it that some of those who have been well-loved nevertheless experience a gnawing, abiding hunger for more? Ari's quest for a father leads her to, of all places, Alaska, allowing Ma to offer up a vivid little portrait of Juneau in the winter, all parkas, dive bars and burly men hunkered down for the duration.

The fluctuations in the narrative power of "The Year She Left Us," a sort of alternating current, at first seem like a flaw in the novel, but by the time I closed the book I felt differently. Charlie and Les may be the more grounded actors in this family drama, but Ari, for all her unreason and adolescent surliness, is the live wire who makes it go. The contrast, between the cluttered, functional, mildly harried third-person circumstances of adulthood and the raw first-person ache of youth is partly what Ma's novel is about. Gran's serene, streamlined and steely concentration on a handful of things that really matter (her Mercedes, women's colleges and one good friend -- "When the two of us got going, we defined the word cackle") rounds out the picture, as full and vexing and self-contradictory and transcendent as any human life.

Shares