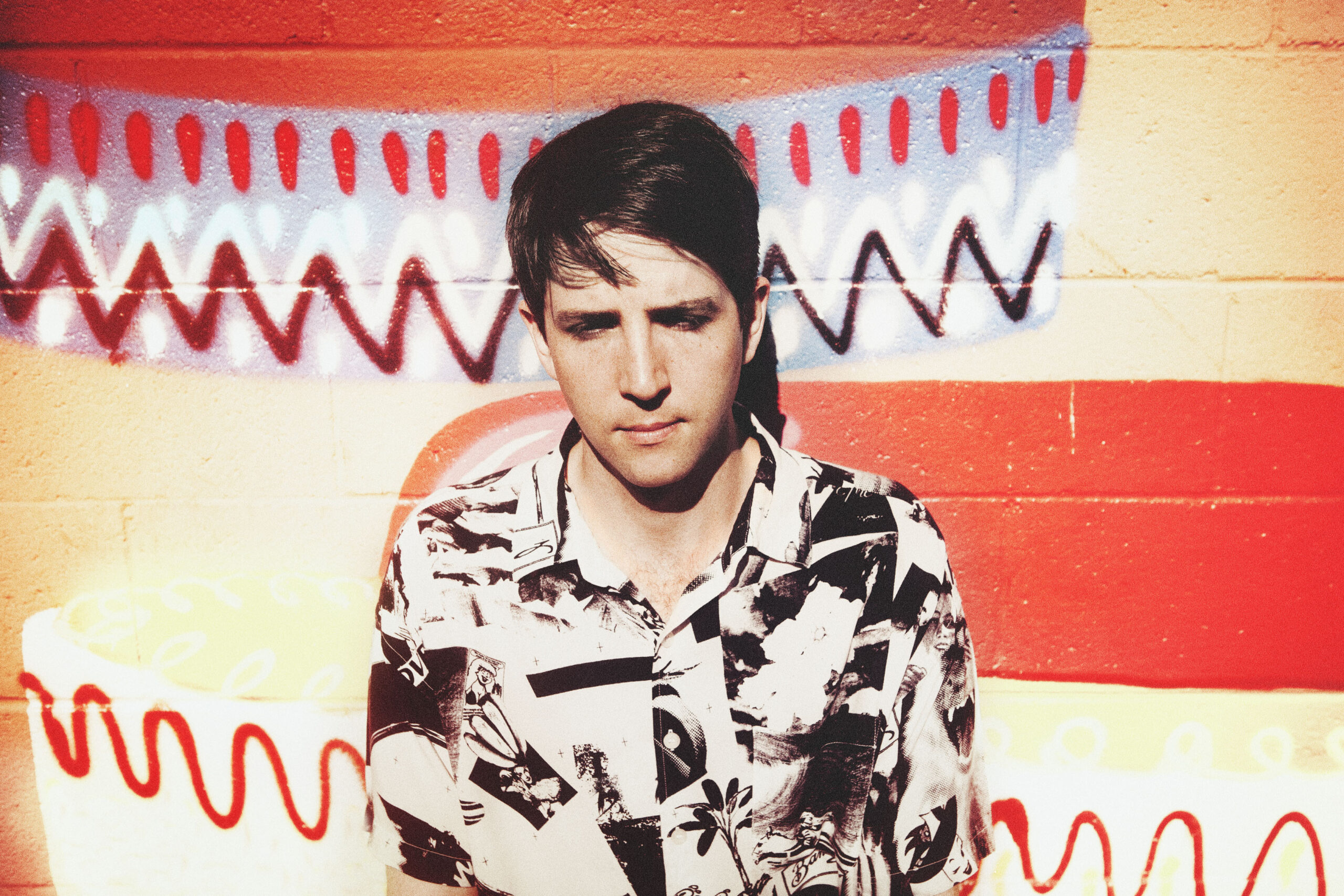

Owen Pallett, wearing a shirt with a brightly colored floral pattern, stood onstage at New York’s Bowery Ballroom on May 14, surrounded by a menagerie of musical instruments — a violin, keyboard and microphone, plus an arrangement of looping pedals by his feet. The show began 13 minutes late, but that wasn’t the only reason for the anxious energy in the air. The audience came in search of something great, something they knew they could expect from a musician and performer of Pallett’s caliber.

Pallett’s music takes shape by playing and looping a series of musical phrases. A live performance is something like watching a tapestry being woven. Each sound — the plucking of a violin, the rapid keyboard, the frantic strings — is individually created, layered and combined with Pallett’s melodious voice.

You may not have heard of the Canadian musician, but you probably have heard his music. It is the string arrangement in Taylor Swift’s “Red”; it is the frantic violin at the beginning of Arcade Fire’s “Empty Room”; it is woven into the soundtrack for “Her” — for which he was nominated for an Academy Award. However, Pallett is not just a behind-the-scenes man; he is an incredibly talented artist and performer in his own right.

Pallett’s latest album, “In Conflict” — his fourth, including two efforts released under the moniker “Final Fantasy” — was released this week to critical acclaim. Salon caught up with Pallett after his performance to discuss the album, his frequent collaborations with Arcade Fire and why Canada produces such great musicians. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

In this album, “In Conflict,” the lyrics seem to be a bit more direct than the storytelling of the previous albums. Are we seeing more Owen Pallett in this? Is this more personal? How did you go about writing this album?

Well, ah! What an impossible question to answer! The thing is, even though my previous records were ostensibly fictional, obviously everything that happened in them happened to me at some point in my life. You know? Or they were drawn from things that had happened to me or happened to my friends. It’s just kind of like a fictionalized version of my experience. You know what I’m saying?

Totally.

“This Lamb Sells Condos,” for example, is kind of the best example of a conversation I overheard as spoken by a developer to either his lover or his wife or somebody. You know? Doesn’t really matter who. And in the song, I kind of gave him some superpowers, and turned her into a dark elf or whatever. And that whole “Dungeons and Dragons” experience was, you know …

With this record, I began by writing these songs that were very, very personal and very specifically descriptive of events that had happened in my life. And I ditched all those songs, because none of them were any good whatsoever. But what came out of writing those songs was that I started to notice that consistently, from song to song, I was very unreliable as a narrator, and the way that I described these events were, themselves, kind of rooted in some sort of fiction. Some sort of strangeness of being that the person I was describing them happening to was no longer the person that I was. And not only that, but the person that had been writing that song a month or two ago was not the person that I was.

I experienced this symptom. Maybe you do too, as a writer. As somebody who documents your thoughts and experiences. That you’ll look back on something you’ve written and be like, “I wrote that?” You know what I’m saying?

Yeah.

It happens to me all the time, when I’m posting, for example, on message boards. And I’ll start to read somebody’s post, and I’ll think, “Oh, that’s so intelligent and interesting,” and then I’ll realize that I posted it. [Laughs]

You know, when I get to the end, I’m like, “Oh, that was me!” And the reverse is true too, when you’re like, “Who is this crazy person?” And then you’re like, “I said that?”

That sort of liminality of experience became the basis for much of all of these songs, and different versions of duality that I’ve experienced or my friends have experienced.

That’s very interesting, and I was actually going to ask you about “This Lamb Sells Condos,” because that was for an entire summer one of my sister’s and my favorite songs. And we would sit, and we would discuss, “What is this about?” And then it made me wonder: Do you ever think about the relationship between your songs and what the audience or the listener is going to take out of it?

I am constantly thinking about how my songs are going to be interpreted, and I’m always surprised whenever I’m working with clients who don’t care about the audience. For example, just off the top of my head, when I’m playing with Arcade Fire, and they’re like, “We’re not going to play ‘No Cars Go‘ tonight.”

And I’m like, “You’re really going to play a show where you don’t play ‘No Cars Go’?” And they’ll be like, “Yeah, we don’t feel like playing it.” I’ll be like, “Aren’t you actually supposed to be thinking about whether or not the audience wants to hear it?” You know what I mean? And they’re like, “No, we don’t care what the audience has to say about this.” And I’m like, “Really! That’s so interesting!” Because every night I’m always, “I want to really kill the audience.” But I guess that’s the difference between being an A-list band and a D-list band, or whatever.

With “This Lamb Sells Condos” especially, much of what “He Poos Clouds” was, and the reason why I had this approach of writing these songs with this fantastical bent, was that I wanted them to function as social commentary. I found it much easier to be critical of certain mechanisms or tendencies in myself and other people if I cloaked these stories in this kind of fantasy world. And when it came to “This Lamb Sells Condos,” I felt so upset and frustrated by the behavior of developers that I kind of said, “Fuck it.” [Laughs]

I remember pointing fingers on this song. I started calling out developers, if not by name then at least by referencing Brad J. Lamb; at the time the advertising slogan was, ‘This Lamb Sells Condos.’

You’re a great storyteller and musician. How does the writing process work for you? How does the storytelling process work? Is it music first?

It’s kind of a bit of a shit-show really. Because my songs are born basically in two different ways — or three ways, actually. Some of them are born on the looping rig. And there are songs that entirely are rooted around that technology — ideas that I want to convey that are tied to my growth and advancement of myself as a looping musician. For example, I’m trying to get away and avoid the sort of compositional things that I’ve done on previous records and try and do new things with looping. And so there’s a whole raft of songs that come out of that.

Then there’s another third of the songs which are entirely generated by work on the piano, and ideas that I have for orchestral music — harmonic sort of ideas.

And then the other third is just stuff that comes from the lyrics. But the way I write lyrics is really kind of specific and strange. I will basically just spend months at a time having three-hour sessions every morning just writing pages and pages and pages of stuff that I think would be fun to sing. And I take all the funniest jokes, and the nicest turns of phrases, and kind of factor them into songs that are essentially already completed and just waiting for the lyrics to carry that melody.

That’s very interesting, because they go together quite seamlessly and I was wondering what came first, the lyrics or the music.

For me, getting the lyrics into a song is pretty much the longest part of the process for me. And oftentimes, when I first start tracking the record, only half of the songs have it figured out. And with both “Heartland” and “In Conflict,” there was a four-month period where the tracks were basically sitting there waiting for the lyrics to be done.

You’ve worked with Arcade Fire quite a bit, including on the score for the movie “Her.” What’s that like?

Yeah, it’s the best. My relation to them is kind of very difficult to pin down, just because the band is an artistically democratic one, beyond Win [Butler] and Régine [Chassagne, Arcade Fire’s lead vocalists], writing the lyrics and melodies to the songs. Everything is sort of generated via think tank. And I’ve always been very transparent with people when credited as being the string arranger on their records. But actually, it’s a collaborative process that, although I sometimes get sole credit, that’s only just because I’m the one using the scoring software. You know? More often than not, the arrangements are born out of dialogue between at least five of us — Win, Régine, me, Richie [Reed Parry] and Sarah [Neufeld], and oftentimes, even more.

And that’s kind of what it was, working with them was, it just got to a point where they needed scoring, they needed piano playing, and they also, I think at the time, they kind of needed me to be an opinionated asshole, to really affect closure on a bunch of cues, and come in and say, “No, this cue is done.” Or, “No, this cue should be redone.” Because I kind of have trouble censoring myself. And hopefully, that’s valuable? They keep asking me back, so …

It’s really incredible to watch you work when you’re live, because when you’re listening to the record, you have this concept that, yes, Owen’s pretty much doing all of this himself, but to actually watch it happen is fascinating. What was the impetus behind making this kind of music?

Well, initially, the Final Fantasy [project] was born out of just me experimenting in the basement with a looping pedal. At the time, there were a lot of bands in Toronto that were using live looping but for more psychedelic sort of jammed-out purposes, and I had this idea that with the looping pedal, I could create very compact pop songs. I had never really written pop songs before. All the songs that I had written, even for bands, were kind of rooted in more, you know, stranger emotions of artistic expression. Though the songs that I initially wrote for those early performances were geared toward consumption, toward other people listening to them. And almost immediately, I had a response in my friends, including my boyfriend, which was really, really positive, like — ‘This is what you should be doing. Please continue working on this.” In the intervening years, I’ve reconciled this desire to create consumable, digestible pieces of music with my own artistic impulse to the point that I felt that by the second record, “He Poos Clouds,” I was feeling like I could and would stand behind the material on that record both as an artist and as a sort of culture producer or whatever. As a line cook. [Laughs].

And I have really just tried to hone my craft and treat people umm, but at the same time, I recognize that one of the appealing features of those early shows was the sort of tangible performance. The fact that every aspect was generated on the fly and so, it’s kind of made me — especially now that bands playing with backing tracks have become much more common, and bands that are performing instruments with no backing tracks have become rarer — even as looping has fallen out of fashion, it actually makes me feel more committed to my practice and want to, you know, just continue to refine and then also never, never cheat. You know what I’m saying?

Yeah, I can even tell when you’re playing, because even if it wasn’t completely discernible to the audience, you would stop if something wasn’t quite right and say, “OK, let’s start this one again, and let’s get the timing.”

Yeah, well, increasingly, too, with every song that we’re writing, we’re kind of trying to challenge ourselves more and more. Because on most of the early songs, I’m not even singing. I’m not singing and playing violin at the same time, I’m just singing over loops I’ve already created. And they’re reliant upon certain compositional tropes, like, “And now, this song gets really layered and complex.” You know?

And now, with the new songs, I’m actually trying to write simpler and make each part very blocky and important and also do the whole thing well, singing so that it’s almost like, when I stop singing, it’s like, “Oh my God!” And while you were singing that verse, there’s this thing that you made, you know?’

What I was noticing is that these new songs, they really build an energy that seemed a bit different than — not any better or worse — but different than some of the previous albums. Was there any sort of different sound that you wanted to try to create on “In Conflict”?

One of the things that I value so much about the music that I make is the sort of limping-ness of it: The fact that it’s the opposite of square, you know? That my rhythms are not performed precisely. Each of them has a problem, you know? And incorporating the bassist and the loud drummer, we were listening a lot to Silver Apples, because it kind of has that same sort of feel of a drummer trying to play along to these unstable oscillators. And you can hear everything kind of speeding up and slowing down; you can hear the drummer falling off the beat a little bit, and it feels very alive and wonderful. So, that was our goal in terms of integrating a rhythm section into the loops. I also wanted to make sure that the performative aspect of what I was doing would not be lost, so that people would still have this exciting sensation of the songs being built before them, but with the added musculature of a rhythm section.

Canada has, at least from my knowledge, a pretty cool support system for independent music, more than in the U.S. Government grants and the like. There are a lot of really talented musicians that come out of Canada. Do you think that the Canadian government has helped that, in a way?

Universal healthcare and no guns, basically. I mean, I’m sorry to your American readers, but yeah, basically, those two things.

That’s a great answer.

It’s the only way you can really have a creative class if the poor people and the not-white people are not being threatened by possible destitution for sickness and/or being shot by rich, white gun owners. I mean, that’s how you make a creative class, you know? It’s very simple. You take care of each other.

I’m sorry to have to say this, and be that asshole Canadian who says the same thing that Canadians always say, but you asked the question, and that’s a Canadian answer. In fact, it constantly surprises me and kind of frustrates me just to continuously read the Gawker version of post-colonial politics transpiring every week on Twitter, etc. Even though I’m completely on that side, I’m like, yeah, things aren’t going to get any better unless you take the guns away. But that’s just the frost-back Canuck, you know, fuckwad speaking.

Are there any topics that you find yourself almost unconsciously coming back to in your lyrics or that continuously need to be explored?

I feel as if pretty much all of my songs are rooted in a few primary and unshakable beliefs — in things that I think are true. I basically am some degree of Theist in that I believe in human kindness, which is actually kind of a radical thing to try and believe in. When all is said and done, it means I kind of can’t really watch a Woody Allen movie — and not for any biographical reasons — but because his characters and the way that things transpire in his movies seem to be not rooted in either kindness or any of that sort of stuff. They seem to be very, very nihilistic. And I’m kind of the opposite of nihilistic. So I can’t really say that there’s any recurring themes. I do think that, essentially, basically fundamental humanism — that human kindness — will triumph over capitalism and its terrors, or gender oppression or any of these sort of things. It is kind of the one unshakable thing that is always recurring in every one of my songs.