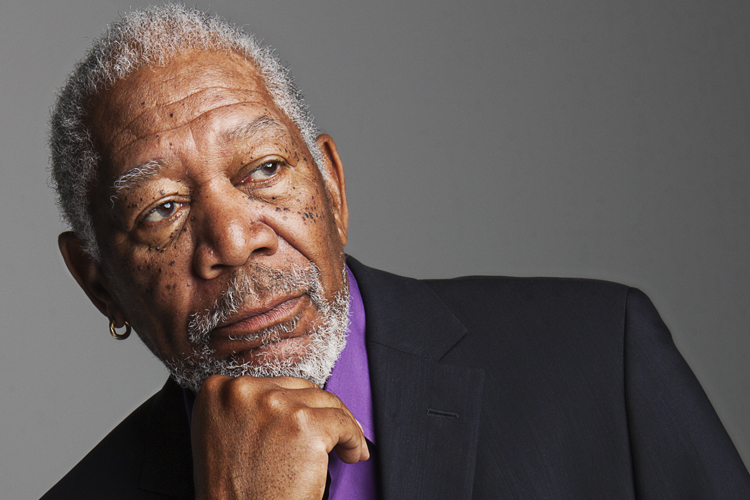

His movie career is more active than ever — but Morgan Freeman is devoting his intellectual energy to the small screen.

The prolific Oscar-winner, who began his career on educational TV with “The Electric Company,” has come full circle: The fifth season of his “Through the Wormhole” premieres Wednesday night at 10 p.m. EDT on the Science Channel. The show, which relies both on Freeman’s gravitas and on up-to-the-minute research, is intended to look at provocative questions — the season premiere, for instance, asks whether there is a genetic basis for poverty.

At a time when science on the tube is, with “Cosmos” on Fox, experiencing a small resurgence, anti-science sentiment, too, has rarely been more robust. And yet Freeman and producer James Younger told Salon that they’re aiming to draw in even those who consider themselves skeptics — “Really, we try not to ever preach to people on any side of a subject,” said Younger. For his part, Freeman insouciantly joked: “I think the people who are resisting the idea of climate change are stupid.”

The season premiere about whether there’s a biological basis for poverty, and there’s a lot of discussion of the divide between the most wealthy in the world and the most poor in the world. Morgan, as narrator, you mention, briefly, your upbringing. I wonder if this topic felt political to you at all?

Freeman: We don’t see that as a political potato at all. There’s been a lot of talk about the 1 percent as opposed to the 99 percent, but I don’t think that really figures into the idea of a world of economics, as it were. Do you know what I mean? The question itself — it’s just sort of under the realm, the idea of genetics. There’s also environmental input, nurturing input and two or three others.

Younger: There are a lot of factors. Genetic is the smallest of factors in how well you do in life, and clearly your environment is the most important thing. We do touch on some interesting new research, which is quite controversial, which touches on different periods in countries’ histories, where different mixes of people create a more or less economically productive society.

Do you know in advance when an episode is going to be particularly controversial, or have some of the episodes that have really taken people aback surprised you?

Freeman: You never really know if a subject is going to be controversial, but sometimes you sit back and say, well, we might get some feedback from this.

Younger: We’re trying to make it fair and evenly balanced so we’re not going to go out there and say it’s completely genetic. We’re not going to show the most fringe research out there and say yes, it is all genetic, look at this research. We try and find thinkers who are basically in the mainstream, but just on one side of an issue or the other. The show is not meant to be very divisive. We’re trying to say, look, here is the range of research out there and there are some interesting effects, much more complicated than asking this simple question like, is poverty genetic? And you realize that most of the film is not about that. It’s a starting point about what are the real reasons for the distribution of wealth in society.

How do you keep people interested and engaged in a time when it seems like people are not that interested in general in more scientific thinking?

Freeman: I don’t know. We are pretty in-house. We just deal with us for the most part, in terms of, What do we want to talk about? And if one of us comes up and says, Why don’t we look into, yada, yada, yada? And if we all think that’s a good idea, then there we go, and we do it.

Younger: We have the people who have come here with a dedication to do that. So we’ve been making these shows, we’ve made 50 of them so far, and what we’ve found is that as we delve deeper into subjects and give people more to chew on, it’s almost like you’re giving respect to the audience. Saying, I’m sure you do want to engage in this, and it turns out they do. They do want to engage in more meaningful things and they keep coming back to us. So not everyone in America wants this kind of show, but there’s really an audience for us out there.

Freeman: And they just want us to keep doing it. And a lot of people say what this show does is make these deep thoughts and subject matter accessible. So, somehow, we are able to talk about things in such a way, that people sit up and say, yeah, I’ve thought about that too.

If you look at a lot of environmental or sociological problems that would seem to have scientific solutions — for instance, climate change — people sometimes are resistant to looking into scientific answers. Do you think the scientific method has fallen out of favor and are you trying to bring it back with the series?

Freeman: My answer to that is too simple, I have to let James talk about it. I think the people who are resisting the idea of climate change are stupid. [laughs]

Younger: I think the show, it’s difficult to make a show about climate change when, what you’re going to do is say, Yes, it’s real, get used to it. I think that’s true but it’s not necessarily good entertainment, because the people who believe it are going to be bummed out and the people who don’t believe are not going to change their minds. So we’re taking a different tack: We’re not trying to change people’s minds, we’re trying to open people’s minds, engage their sense of philosophy and wonder about how the world works. So, really, we try not to ever preach to people on any side of a subject. But we also aren’t afraid to say anything about anything. Is poverty genetic? Well, we aren’t afraid to ask the question. A couple seasons ago we asked, Is there a superior race? We’re not afraid to ask the question. So we go anywhere with the scientific method and we’ll allow people to make their own minds up.

Morgan, some of your other work, from “Deep Impact” to, this year alone, “Transcendence” and “Lucy,” has been science fiction. I wonder if it’s been difficult as someone who’s clearly interested in real science to do a sci-fi film that diverges from scientific reality.

Freeman: When I was about 9 years old, I think, or maybe a little later than that, I read a book called “25,000 Leagues Under the Sea.” All science fiction. Do I have to go on? The point is that when that was written when Jules Verne wrote it in 1800-something, they were in a submarine called the Nautilus. Well, the Nautilus is a reality. Science fiction is sometimes just science prophecy. So I don’t have any compunctions about that … particularly if it’s well-written.

To what degree do you introduce ideas and where do those ideas come from? Do you read journals, do you read the newspaper, when you’re thinking about topics for the show?

Freeman: I don’t read journals, but I do read the newspaper and I do watch a lot of television. And life itself, to me, presents a lot of questions, a lot of things we might want to entertain as subject matter.

Younger: In Season 5, we’re going to do an episode of one of Morgan’s questions, why does life even come into being? So Morgan will introduce a few ideas and then we talk with him about the ideas we have. And sometimes he’ll say, I don’t like that one, let’s not do that. Most of the time you’ll add a few other questions in there with your perspective.

Why does life even exist, that’s the really heavy stuff.

Freeman: I’ve been learning a lot about enzymes, and an enzyme is a catalyst — so life from its earliest conception, from its earliest days, we’ve figured out how to replicate it. That’s a lot of chemistry. They’ve figured out how life figured out how to be life. And that’s a deep thought.

How do you drill down to that in an hour?

Freeman: We don’t have to drill down to it in an hour; we can have continued shows.

Younger: We call a lot of guys, we ask about it, and probably speak to 20 or 30 people and figure out six or seven that are going to be in one episode, and figure out a way to weave the story through them. It’s a long process of development.

If you had to compare it to a show like “Cosmos,” how do the shows’ methods differ?

Freeman: Compare our shows to other shows of this nature?

What sets this show apart?

Younger: Well Mr. Freeman is Mr. Freeman.

Freeman: We don’t … “Cosmos” is a good show, and in a similar vein. We have better writing. I think our writers are cleverer, our graphics are more immediate, they are better at introducing the subject or clarifying the subject.

Younger: We try to be really thought-provoking and we try to also have a little bit of fun. We have like a cartoon in there where a proton is played by a funny, colorful character doing things. We make people laugh sometimes.

I found it to be so familiar, from the movies, to have Mr. Freeman act as an authoritative voice, someone I immediately trusted before I even knew what the subject was. I wonder if you, Mr. Freeman, have any theory for why you’ve played God, the president, or an authority figure so many times?

Freeman: Do I have an answer to that, a reason a why?

Yes. Why do people trust you to explain things?

Freeman: I have no idea at all. I don’t know why. Well, I do have one idea. I’m not a good liar.