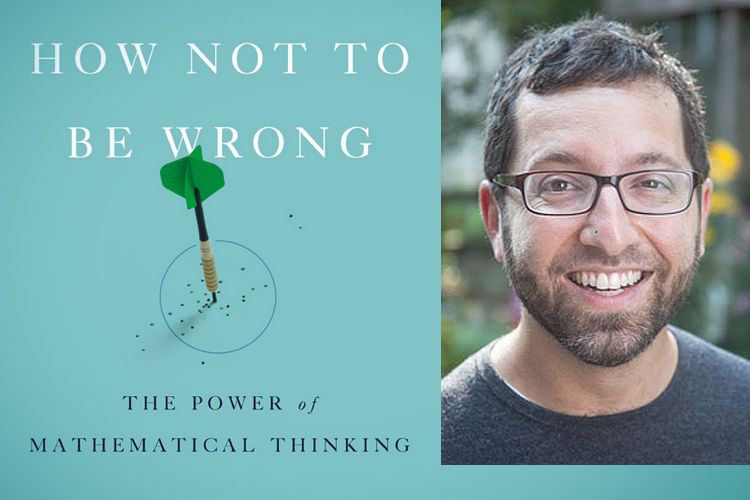

Math, as author and University of Wisconsin professor Jordan Ellenberg writes, may not be the most readily accessible subject in school. When faced with a complex equation a student may ask, “When am I ever going to use this?” In his book “How Not to Be Wrong,” Ellenberg surprises readers with the prevalence of math in everyday life, and through a series of examples and stories highlights the capabilities of mathematical thinking. Math reaches deep into everyday politics, culture and even the engagement of war.

To Ellenberg, math isn’t separate from the humanities, it is interwoven in the human experience. It is a category of thinking: one of the many tools humans use to take stock of our complex world. In “How Not to Be Wrong,” he presents his case in a way that is readily accessible both to readers with a math background, as well as those who have not laid eyes on the Pythagorean theorem since their school days.

Salon spoke to Ellenberg about his book, about Nate Silver and data journalism, and about “flip-flopping” politicians. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

What made you decide to write this book?

Well, it was something I had in mind for a long time – even down to the title for like, gosh, seven or eight years. Worn out. But you know the academic life doesn’t leave open a lot of time for doing other stuff, so it was something that I kind of – you know I’ve been doing a lot of journalism and kind of slowly increasing the scale in which I did things. Learning to write longer pieces and stuff like that, and I guess what I have found out is that there just seems to be an endless interest in reading about math, and especially the mathematical way of looking at general things in the world. I mean, your experience as a professor, you spend a lot of time talking about math to people who have been forced to be there, to the point that it’s sort of a surprise when you remember that, actually, in the real world, people are really interested and come to you of their own choice to learn about math.

So, I hate to admit it, but I will. Around precalculus — which at my school was a combination of precalculus and statistics — I discovered I wasn’t very good at math. That was really disheartening, because I wanted to be a doctor at that point in time. So I was a little nervous approaching the book, because I thought, “Oh gosh, it’s a book about math!” And yet the book was very approachable and actually got me interested because of the way that math was applied to the real world, and the way you told those stories. So how did you decide which stories to tell?

First of all, I want to say that somebody in your position is like absolutely the ideal reader of the book, because I do feel like people have a weird way of thinking about math where they decide whether they’re good at it or bad at it, in a way that I think people don’t do with reading books. People read different kinds of things, but nobody’s like, “Oh, I realized I was bad at reading. So I didn’t read anymore.” You know what I mean?

But I think math has this special feature, that people kind of categorize themselves as “math people” or “not math people.” And one of the messages of the book for me is that we are all “math people.” We’re all thinking about things in a mathematical way. It’s not like a thing that was invented and imposed on us, even though it can look like that because of the language we use and the formal symbols. It really is a codification of what we’re doing anyway. So I tried to write about it in a way that ties it very tightly to – I don’t know what to call it except thinking. It is a form of thinking. A particularly powerful form. And everybody thinks.

Is there a way that you would go about teaching math differently, or a way that you do go about teaching math differently, even to your college students?

Well, it’s a great question and I think writing the book has affected my teaching, as it forced me to think really carefully within myself and with the book people and see how people respond about how to present mathematical material and mathematical reasoning. But I will say this: I don’t think there’s a magic bullet in the sense that … You know, I’ve taught enough courses where you go in with the idea, “I’m gonna do everything completely differently, and it’s going to be awesome, and we’ll throw aside the old way that we do things.” And you always discover that there’s a reason people do things the way that they’ve been doing them. It may not be a good reason. But it’s better than for no reason.

I do think we can connect the curriculum to the real world more, and in some sense, that is already happening. You just said, you took the pre-calculus course, which was a combination of elementary functions and stats? That would not have been the case when I was in high school. I’m not that old. So the fact that statistics has penetrated into the high-school curriculum is exactly because people have looked around and said, “What are the parts of math that really hook up with the kinds of reasoning and the kinds of questions these kids are actually going to be asking themselves and grappling with as adults?” And I think there’s no question that problems about statistics and problems about uncertainty and problems and probability are a huge part of that, and that’s why they make up such a huge part of the book actually.

If in the end, what you’re going to be judged on is how well do the kids do on a test; you have no choice as a teacher but to make sure the kids do well on the test. And then a huge amount of responsibility falls on the test-writers to write tests that have this property that, the kids who do well on them are roughly the same kids who have learned the lessons that we want them to learn. That is not easy. I think the folks who write tests work very hard to get as close to that as they can, but it’s not easy.

The book was about thinking, and not so much presenting a set of data and saying this is how you should think. Was that a conscious decision you made? You also talk about Nate Silver — what do you think about data journalism?

I think that is how everyone who’s serious about the subject approaches it. And that’s how Nate Silver approaches it, by the way. I mean I don’t know him well, but I’ve read his book. I reviewed it; I’ve met him. And he’s kind of a hero of the book. Let me put it this way: You say, OK, there’s a question of are you going to use math thinking or are you really going to just use math data? Here’s the important lesson: If you use the math data without the math thinking you’re completely screwed. What’s important is the mathematical process of thought and the math reasoning. And Nate would certainly say that. I’m certain he would endorse that.

How do you make sure that the data journalism is responsible and doesn’t mislead readers?

I think the responsibility that people have who are going to write about things in a quantitative way is exactly to resist that. And again this is an area where I think Nate is very good. To not say, to sort of always say, “Numbers measure what they measure, they can be quite precise about what they measure. They don’t measure what they don’t measure, and we better not pretend that they’re measuring what they’re not.” They’re a very powerful thing. You have to use them responsibly, because I think there’s no question data and numbers and math and statistics enjoy an enormous amount of cultural prestige. If you throw them around people think you know what you’re talking about. I happen to think we do know what we’re talking about. But you have to be responsible about it. And by the way, I don’t think that’s new.

You’re absolutely right that we’re in the middle of the gold rush of data journalism but the fact that … the weight that’s assigned and the credence assigned to numbers is not a new thing. It’s always been that way. And I think, how to put it, I think, I mean this is kind of meta I guess, I can’t speak for Nate Silver who obviously is a very big name in his area, but I do think people do start to panic and they looked at him and we’re like, oh, he says there’s nothing but numbers and there’s no thinking and no room for the human or whatever. That’s certainly not Nate’s stance, that’s certainly not my stance, as I hope the book shows. The book is not about math supremacy. This is like one tool that has been a central part of the way humans think about things when we think carefully for like 3,000 years, and so why put it aside? Why put it down when it’s one of the crucial tools we have. But of course it’s only one of those tools. And in the book there’s lots of philosophers, there’s poets. We put things together when we try to think about that.

Something else seems to be popular right now: people pitting STEM education versus arts education and the humanities. Do you think that there’s a way that they interplay?

Yeah. In essence math is in the humanities, in the sense that it is a fundamental part of the human condition, it’s a fundamental part of what makes us human, always has been. Imagining people not thinking mathematically is like thinking about people not making music. We’ve been doing it since there was civilization and we always will be doing it. It’s like one of the central activities that we undertake. And obviously there are people who do it more and people who do it less. And there are people who call themselves unmusical but they’re probably not completely unmusical right? So I would obviously, I would hope that those things would not be in opposition and I don’t think they have to be.

So just as there is a gold rush of digital journalism, you probably know there’s a gold rush of digital humanities, of people who are saying, “How can we use those tools as one of the tools we use when we think about books? When we think about music?”

In music that’s pretty old actually, it’s not a new thing in music, but it is new in literary study. And the thing is, you have to not have it be based on math supremacy, because math supremacy is always wrong. It’s actually only pretty recently that the practice of biology was really very mathematical. I mean it’s been partly mathematical for a long time, but in general mathematical biology is much bigger now than it ever has been. And when that’s done right, the way it’s done is not math statisticians walking into the room saying, “Now let me tell you about biology.” It’s done absolutely hand-in-hand with the biologists who actually are thinking about what’s going on and need a new tool. And a tool that we’ve been forging in math over many, many years.

The title of the book is “How Not to Be Wrong,” and at the end of the book it turns out that how not to be wrong, or how to be right, is to accept that there is room for error. When dealing with error, and when accepting that there is uncertainty in data and statistics, how do you root out irresponsible math?

I think that’s part of my educational mission and the educational mission of anybody who does math. We have a belief that the more you know about where it comes from, the less intimidating it is. We want to believe – I seriously tell this story, because it’s so essential to what the book is and in some sense what my life is – which is the story about the rectangle and how you know that 6 times 8 is the same as 8 times 6. We as teachers, we want to create a world in which people agree about the facts of mathematics because they can perceive directly that they’re true, not because we said they’re true. If people believe those things on our authority then we fail. Because what’s special about math is it’s the only subject where the reason to believe things is because you can just – with words, not instantly – but you can perceive it as true that 6 times 8 has to be 8 times 6, then you can be like, “I’m afraid you’re wrong.”

It’s not true in history. It’s not true, on some level, if a teacher tells you what happened in the Civil War, you’re not going to be able to check. You’re comparing somebody else’s authority to their authority. Math is where we train people to create knowledge by themselves, that’s what it’s doing. And that’s why it’s so important. So I mean, when you ask, “How do people deal with these things responsibly?” I think it is an educational question. I think the more people understand how those numbers are produced, the more they understand what to take it for. I mean, numbers are great, but they should be – not just because they’re numbers – but because we understand how they work and how they were produced. That’s the ideal. We climb towards it with slow progress.

In politics if you do end up saying like, “Oh well, something has changed, I’m going to change my view,” you’re called a “flip-flopper,” which is a negative term for a candidate. Do you have any suggestions or thoughts about how we can change the cultural perception to allow it to be OK to be uncertain — to not know how many people are going to have tuberculosis in 2050?

What separates a politician from a professor like me is that the politician’s job is to be able to say things that by all rights ought to be unpalatable and ought to make them unpopular, and you have to sort of assuage other people’s fear. That’s why I didn’t become a politician. So I believe a sufficiently skilled politician could do this. I think it has to come back to Silver again. I would not have thought that he could have done what he did. I would not have thought he could have taken doubt — and that mess of uncertainty — and have such a massive popular buy-in. He did it because he’s a great writer, in the end.

In the same way, a politician could do it if he’s a great politician and a great communicator. I think in some sense, that’s what it takes. And it’s not a mathematical skill, it’s not going to be the person who’s the greatest statistician of their age. It’s going to be the person who is the greatest communicator of their age. So I believe a sufficiently good politician could do it. And I think it’s a complicated problem because, it’s a question of what a voter is looking for from their elected representative. Do they want someone who is maximally likely to do the correct thing, or do they want someone who they know what they’re getting? You elect somebody and they’re in their for four years. The benefit of electing someone who never changes their mind is you know what you’re getting. It’s not unreasonable to want that.

At the same time, in real life if you knew somebody who never, ever changed their minds, no matter what or how circumstances change, you wouldn’t say that they had principles, you would say they were an idiot. I mean, that sort of note, the Bayesian stuff I talk about, I don’t need to hit it so hard again, you could write a whole book, in fact people have written whole books about Bayesianism and Bayesian philosophy, I sort of touch on it in the book when I talk about the readings of psychics. I mean, Bayesianism is all about, how do we formalize the process by which our beliefs change when we encounter new evidence. And like I said, there are super-hardcore people who feel like that process can and should be fully formalized. I don’t go that far. But the point is, nowadays, nobody is totally non-Bayesian, everybody gets that it’s a good way to think about our mental processes when they’re functioning incorrectly, is that you kind of have these beliefs in certain things and as evidence comes in they change. They should change. It’s weird if they don’t change.