What makes a novel, or any other piece of writing, “literature”? There are at least two ways to answer that question. If you’re Ruth Graham, author of a recent essay in Slate titled “Against YA: Adults Should Be Embarrassed to Read Children’s Books,” you might assert that real literature (for adults, at least) consists of “stories that confound and discomfit,” featuring an “emotional and moral ambiguity” that’s “nowhere in evidence in YA [Young Adult] fiction.” Or you might decide to define the essence of “literature” as residing in everything a written text can do that other forms of storytelling cannot.

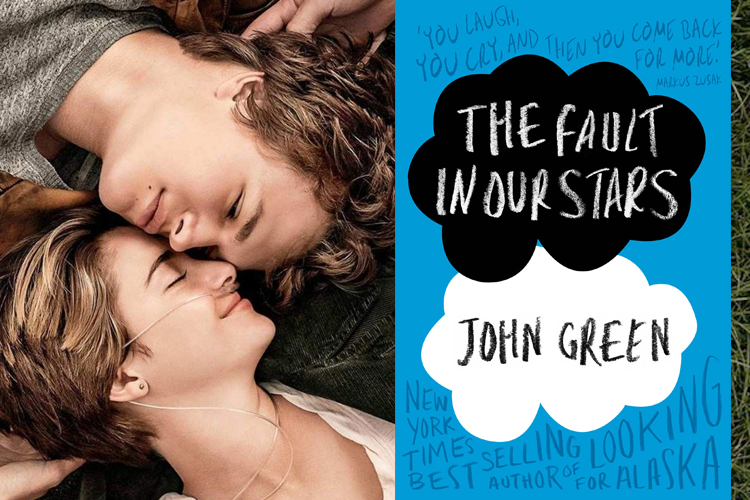

It just so happens that this week both of these notions of literature have converged on a single object: “The Fault in Our Stars,” a bestselling YA novel by John Green. A film version of the book, directed by Josh Boone and starring Shailene Woodley and Ansel Elgort, has just opened. Having read, loved and reviewed the novel when it was first published, I remember feeling some trepidation when the news of the movie deal first leaked out. I didn’t then and I don’t now believe that the finest aspects of Green’s novel — the voice of its first-person narrator, Hazel Grace Lancaster, and the intimate perspective it offers of her psyche — could ever adequately be captured on film. Salon’s film critic, Andrew O’Hehir, who has not read the book, hated the movie, but even he concedes that its best bits were Hazel’s voice-overs, all taken directly from the novel.

I liked the movie better than Andrew did, but there’s a lot I winced at as well, surely for some of the same reasons that led New York Times film critic A.O. Scott to file his own mixed review. He calls the film, a “depiction — really a celebration — of adolescent narcissism” that “short-circuits any potential criticism through a combination of winsome modesty and brazen manipulation.”

For the uninitiated, 16-year-old Hazel is in the midst of an uncertain recovery from a form of cancer that almost killed her. An experimental drug has halted the disease for the time being (no one knows how long it will go on doing so), but she’s not strong and she needs to wear a cannula attached to an oxygen tank at all times in order to breathe. Her mother nags her into attending a support group, where she meets Augustus Waters, 17, a former jock who lost a leg to osteosarcoma and is currently in remission. A halting romance kindles. As for the ending, let’s just say it makes most readers and (to judge by the audience I saw it with) most moviegoers cry.

What’s striking about Green’s novel is the careful way it reproduces what Hazel calls “the Republic of Cancervania.” It’s a subculture of teenagers who are burdened not only with a deadly and debilitating illness, but also with the weight of their parents’ fear and grief, the puzzle of how to get through one of life’s thorniest transitions when you may not make to the other side, and a cultural and social superstructure — from the Make-a-Wish Foundation to support groups to formulaic stories of adversity and enlightenment — imposed on them by an adult world desperately trying to spin their shitty luck into some kind of inspirational gold. Or at least an easier way to get to sleep at night.

Adolescent skepticism in the face of adult injustice, hypocrisy and denial is one of YA’s perennial themes, but Hazel, Augustus and their similarly ill friends are also alienated from their peers, kids who have no idea how to integrate oxygen tanks and prosthetic legs into hanging out at the mall or playing basketball. Not that the typical teenage pursuits hold that much appeal anymore. Augustus, formerly “the prototypical white Hoosier kid … Resurrecting the lost art of the midrange jumper,” tells Hazel about making dozens of consecutive, “existentially fraught free throws” the day before his leg was amputated. “All at once, I couldn’t figure out why I was methodically tossing a spherical object through a toroidal object. It seems like the stupidest thing I could possibly do.”

So life — however much they have left of it — for Hazel and Augustus is the navigation of many nested ironies. One reason why the novel version of “The Fault in Our Stars” feels much deeper than the movie is the access it offers to the counter-narratives constantly running through Hazel’s mind, all the things she can never express, from her fond exasperation at having to tell Augustus she thinks “V for Vendetta” is a “pretty great” movie (“It wasn’t, really. It was kind of a boy movie. I don’t know why boys expect us to like boy movies. We don’t expect them to like girl movies”) to thinking, as she smiles at a framed inspirational motto a friend’s parent has hung on the wall, “its stupidity and lack of sophistication could be plumbed for centuries.”

The problem of how to feel strongly or deeply in a world of multiple incompatible cultures, of doubled or even tripled meanings and in what must inevitably be a state of acute self-consciousness — all of this was a core theme for the late novelist David Foster Wallace. “The Fault in Our Stars” is in many respects a conversation with Wallace. Hazel’s favorite novel, “An Imperial Affliction,” is a riff on “Infinite Jest” (the title of which, like Green’s, was taken from Shakespeare). It ends in mid-sentence, like Wallace’s first novel, “The Broom of the System.” The mathematical and philosophical concept of infinity, which interested Wallace so much that he wrote a nonfiction account of it, is the metaphor Hazel chooses when asked to write about her relationship with Augustus.

Not much of this comes across in Boone’s film, suspended as it is between the desire to be true to Green’s book (the screenplay is not by any means dumb) and the imperative to deliver a sufficiently commercial weeper. The sharper edges of the novel have been filed down, like the dying Hazel’s resentment of her parents or her response to her friend Isaac when he reviles his (healthy) ex-girlfriend for saying she “can’t handle” an upcoming surgery that will leave him blind: “To be fair,” says Hazel, “she probably can’t handle it. Neither can you, but she doesn’t have to handle it. And you do.” There’s a lot of hugging and a whole lot of sappy pop music, rife with tremulous and reedy vocals, welling up behind travelogue shots of Amsterdam, where Hazel and Augustus venture on a pilgrimage to meet the reclusive author of “An Imperial Affliction” (a fantastically scabrous Willem Dafoe). Even when the young actors are supposed to be ravaged by cancer, they look preposterously healthy. Little of the hideous physical damage wrought by the disease appears on the screen.

Although Laura-Linney lookalike Woodley acquits herself well as Hazel, Elgort is out of his depth in the tricky role of Augustus, delivering a performance that’s 84 percent smirking. In the novel, we can view Augustus only retrospectively, through Hazel’s reluctantly starry eyes and as Augustus chose to present himself to her, the Augustus both of them need to believe in. This is a factor that Graham, in her Slate essay, doesn’t seem to have taken into account when she derides the novel for its idealized depiction of him. Graham professes to be the only reader to have finished Green’s book without shedding a tear, and the perfection of Augustus seems to be the primary reason why. It’s perplexing to read a complaint about the lack of literary sophistication in Young Adult fiction from a critic who seems insensible to how literary effects are achieved. The impression left by Graham’s description of “The Fault in Our Stars” is that when she read Green’s book, all she could see in it were those elements that would become Boone’s movie.

As for Graham’s complaints about the genre as a whole, it’s certainly true that there is a lot of crappy, formulaic, simple-minded and above all sentimental YA out there, but of course there’s also an awful lot of adult fiction with the very same qualities. What Graham asserts, however, is that even the best YA fiction (the only example she offers besides “The Fault in Our Stars” is Rainbow Rowell’s “Eleanor and Park,” a book I haven’t read) falls short of the standards of the better adult fiction because it caters to a myopic view of the adolescent perspective. Adults who read it “abandon the mature insights into that perspective that they (supposedly) have acquired as adults.” Furthermore YA novels “consistently indulge in the kind of endings that teenagers want to see, but which adult readers ought to reject as far too simple. YA endings are uniformly satisfying, whether that satisfaction comes through weeping or cheering.”

But, again, here Graham makes the naive mistake of confusing a narrator’s thoughts and values with the author’s. Hazel wants to meet Peter van Houten, the author of “An Imperial Affliction,” so she can ask him to resolve the unresolved ending of his novel. Graham quotes Hazel telling Augustus that she craves more narrative closure: “I know it’s a very literary decision and everything and probably part of the reason I love the book so much, but there is something to recommend a story that ends.” Hazel is halfway to understanding that van Houten’s refusal to wrap things up tidily might be integral to what she finds meaningful in his work, yet — as even Graham seems willing to admit — her desire to know is still understandable.

But, and here is the important part: van Houten, even when the two lovers travel across an ocean to meet him, refuses to answer. Hazel never gets to know what happens to the characters in “An Imperial Affliction” after the novel ends. Just as she’ll never get to know why she and Augustus got sick, why she was one of the few patients to respond to that experimental drug, why some of her friends will die young and others won’t, what will happen to the people she loves after she dies. Like the rest of us, all she will ever know is that some people have to handle it and some people don’t. And just to put a cherry on top, she gets a reminder that even when you do know what causes a wonderful person to die young, the reason doesn’t usually help much. Her Amsterdam trip includes a visit to the Anne Frank House.

Why kind and innocent people suffer and perish may be one of the oldest and most difficult questions humanity asks itself. If you want to believe in a benevolent providence or a loving God or that people are basically good, as Anne Frank did and as (I think) Hazel and Augustus do, then this problem is called theodicy. But even if you can get by without some form of faith, the questions proliferate. Do life’s cruelties, does its very brevity, invalidate its joys? Is there a possibility — let alone a reason — for going on in spite of all this? I’m going to go out on a limb here and call these momentous concerns, not the stuff of what Graham dismisses as “maudlin teen dramas.”

Graham’s counterexample to “The Fault in Our Stars” is J.M Ledgard’s adult novel “Submergence.” She praises it for containing “weird facts, astonishing sentences, deeply unfamiliar (to me) characters, and big ideas about time and space and science and love.” I’m sure it does. But so does Green’s novel. I can’t, of course, compel Graham to recognize the merits I perceive in the book, but I will say that before I read it I did not know about Cancervania. I did not know any teenagers whose maturation was kicked into hyperdrive by an untimely confrontation with mortality or about their ambivalence upon receiving “cancer perks” or that they might be living in a state of emotional limbo and what that feels like. Now I do, to the extent that any of us come to know anything from fiction.

I haven’t read “Submergence,” but the “big ideas” confronted by “The Fault in Our Stars” don’t strike me as so very different from those faced by, say, the young characters in Kazuo Ishiguro’s great novel “Never Let Me Go.” Green may offer a more accessible treatment of the same themes, but it’s not a less honest one. A work of art is only sentimental to the extent that it lies to its audience, and I just don’t see lies in Green’s novel. What I see in Graham’s essay is a critic who just doesn’t know how to read it.