A week before my childhood best friend and I got busted by school authorities for stalking and threatening several students and a teacher. I wrote in my diary, “Soon, everything will be running on the right road.”

The prose would be absurd, if it weren’t for the context. I met Amy (not her real name) at summer camp when we were 8. She was fat and wore thick glasses, while I was sickly skinny with teeth so crooked you could still see them when I closed my mouth. We were instant friends, who communicated not on the actualities of our lives, but through story. We wrote them together, about everything, constantly. We were each other’s first audiences, not for the world as it was, but for the world as we wished we could summon it into being.

By high school, our tales had become less fanciful, and we were more interested in melodrama. Our characters were no longer fantastic and were, instead, fictionalized versions of our classmates and teachers. What if those two friends were really sleeping together? What if that teacher were Amy’s real father? And one day, What if we threatened to kill him? What would he do?

When we got caught slipping a note to that effect into a teacher’s school mailbox, Amy took the brunt of the blame, in part because I was the better liar and more timid child. We were forbidden from speaking to each other again, and she had to go to therapy three times a week. Meanwhile, I got off with a brutal lecture and years of suspicion.

While she had always been the dominant personality in our pairing and had started the darker escalation of our stories, the fact remains I had been her friend through months of this, engaged in these endless what-if scenarios, and suggested increasingly ghoulish ones to win her approval and keep her interested.

While I remember often being afraid that we would go too far, I don’t ever remember being clear on what too far was. I was never scared enough to tell her to stop, to walk away, or to tell an adult. The story, you see, was always the most important thing.

* * *

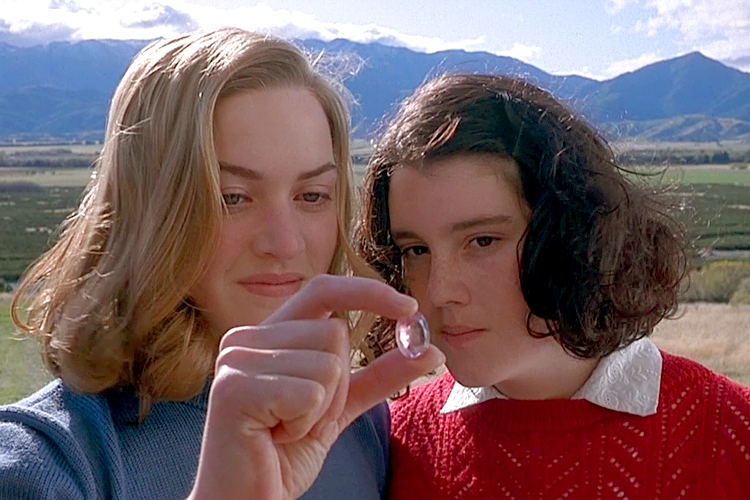

Many years later, I watched Peter Jackson’s “Heavenly Creatures” with a group of creative women like myself. The film tells the story of New Zealand’s infamous Parker-Hulme murder case in which two girls with an obsessive, story-based friendship ultimately kill one of the girls’ mothers. One of the pair, the former Juliet Hulme, is today the best-selling mystery novelist Anne Perry.

As the credits rolled, the women around me, to a one, said they felt like the story could have been – with less luck or divine intervention – their own. Each and every one of them had had an Amy. Some were still in touch with theirs. One pair were even still best friends, after, they insisted, a sojourn of separation during which they both got their heads on a little straighter.

In the 20 years since the release of “Heavenly Creatures,” I have had cause to think of it often. While I have seen Amy just a handful of times since leaving home for college, the creation of story has remained my primary relationship tool. When I meet you, I will tell you a story. And if you tell one back to me, frantic to find the connection between our two tales, we will become friends.

One of those friends is someone with whom I’ve written more than a million words. Another is my romantic partner of over seven years. A third is my co-author, with whom my first novel comes out in September. Thankfully, none of them are my Amy, and I have not been an Amy to any of them.

But in the wake of the Slenderman stabbing in Wisconsin, I am preoccupied by the existence of these obsessive, narratively focused dyads in my life. From that night at the movies in 1994 – and many stories and confessions I have heard since — I know they are not unusual. Yet the media seems mystified by them and by the love of story that comes with them. Could the Wisconsin girls not tell fantasy from reality? Were they mentally disturbed? Did the story lead them astray?

As a difficult child in a difficult world, I learned young that in writing stories there is great power. As a creator, I was both listener and conjurer. It was not that I did not know the difference between fantasy and reality, but rather, that I had been given one gift in my loneliness – an ability to bridge the two.

Stories were not what led Amy and me astray. Rather, they were the flotsam we grabbed onto in desperate hope of tethering ourselves to a world we did not understand and felt powerless to navigate. When we were caught, the people around us only saw us drowning in our private worlds, but those worlds were the rope with which we were trying to save ourselves. We were just brutal, foolish and, at least in my case, cowardly, in the ways we tried to climb out of the churning sea of our fears and insecurities.

I don’t know what happened in Wisconsin, and I am reluctant to join the speculating hordes. Despite this, I keep asking not what would drive two girls to do such a thing, but whether it was just timing and good luck that Amy and I never did?

Despite our societal love of blaming video games, violence on TV, and the mystifying cultural moments of generations not our own, blaming Slenderman or a child’s preoccupation with fantasy for the stabbing seems, at best, misdirected. After all, it’s easier to ban content and lecture about the dangers of an overactive imagination than it is to confront whatever set of circumstances made these girls – and many girls like them – need the secret world of shared story so badly.

The creation of story is intimacy. Yet, we keep our experiences of such intimacy largely secret, preventing others from learning from them. After all, stories aren’t real; we’re not supposed to take them so seriously; it’s embarrassing when they mean so much to us.

That’s what I was taught, both before and after Amy. I doubt I am alone in the hesitancy to say I’ve made a new friend because of a shared love of a TV show or the reluctance to admit I’ve fallen in love because late at night, half-asleep I was asked to tell her a story in the dark.

Certainly, the women I saw “Heavenly Creatures” with would agree with me that this peculiar shaming of fiction-based connection exists and is pernicious. And I cannot imagine that we were the only group of women whispering in the fading glow of that film, it could have been me.