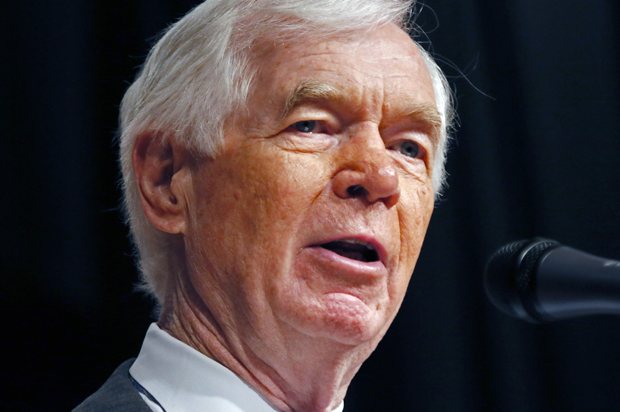

After his near-miss in the primary, Republican U.S. Sen. Thad Cochran’s campaign has tried an unusual strategy during the runoff election: He’s focused on persuading black Democrats to cross over and vote in the Republican primary. But if history is any indication, it’s a strategy that’s doomed to fail. Why? Because whoever said that politics is a game of addition, not subtraction, probably wasn’t talking about Mississippi — and its sordid racial history. Let me explain.

* * *

In his 1949 landmark book “Southern Politics,” the famed political scientist V.O. Key concluded that the politics of the South “revolves around the position of the Negro … Whatever phase of the Southern political process one seeks to understand, sooner or later the trail of inquiry leads to the Negro.”

For centuries, a small minority — the wealthy whites of the fertile Black Belt, named for its rich, alluvial lowland soil and housing a majority black population whose exploited labor fueled the region’s prosperity — convinced the rest of the South to suppress all attempts at black advancement. Poor and working-class whites across the region mostly accepted the Black Belt-propagated myth of Negro inferiority that helped unify the South in national political battles to preserve slavery, quash biracial Populist revolts around the turn of the 19th century, lock in iron-clad segregation, and bar black political participation. All of these efforts perpetuated severe racial inequality across the region: White planters were the original top 1 percent, the original designers of an incredibly successful Koch-like strategy to convince working-class white voters to elevate cultural interests over pocketbook concerns. Indeed, the dominant theories of Southern political and economic development hinge on black repression.

For most of the 20th century, the Mississippi Democratic Party – as with the Democratic Party in many Southern states – housed these two distinct factions. Mississippi politics was a battle between the delta planters and the poor white “peckerwoods,” as Key called them. The planters wanted low taxes and limited public services; the peckerwoods favored the New Deal and the electricity and jobs it brought to the rural South. And the overwhelmingly poor (and white) piney woods region did more than just accept the Black Belt’s racial worldview; it produced pols like Sen. Theodore Bilbo, whose fire-breathing racial rhetoric contrasted with that of more affluent Southern pols such as Georgia’s Richard Russell and Mississippi’s James Eastland, who typically guised their civil rights opposition in constitutional terms. (Bilbo argued on the Senate floor that the passage of anti-lynching legislation would increase “raping, mobbing, and lynching … a thousandfold” and said that its proponents would have “the blood of the raped and outraged daughters of Dixie” on their hands; he wrote a book titled “Take Your Choice: Separation or Mongrelization.”)

These divisions persist in Mississippi politics – except now they exist within the Republican Party instead. As the Mississippi Republican Party’s elder statesman, Cochran, true to his affluent Jackson upbringing, embodies the more measured tone of the planter class. Conversely, the fiery conservative McDaniel was born and raised in a rural county so poor and depopulated in the mid-19th century that it became a haven for non-slave-holding Confederate deserters who saw little reason to sacrifice for the cause. And McDaniel’s retrograde rhetoric on race and sex bears uncomfortable resemblances to the vile Bilbo orations of yesteryear.

But despite sharp cleavages, Mississippi Democrats remained united in order to perpetuate segregation, since splintering would have led to the possibility of Republican victories that could derail the South’s primary strength in national politics: the seniority of its congressional delegation. Like those from Georgia and Virginia, Mississippi’s delegation clung to key committee chairmanships that they leveraged to bottle up civil rights legislation for decades.

And so for a century after the Civil War, one thing remained constant throughout the South: Black people were to be prevented from voting by any means necessary. In accordance with Key’s “polarization hypothesis,” which posited that black repression would be worst in areas where black populations were highest, South Carolina and Mississippi led the way in this effort. As one of the South’s most fiery demagogues, South Carolina Sen. “Pitchfork” Ben Tillman said, “We have done our level best [to disenfranchise blacks] … we have scratched our heads to find out how we could eliminate the last one of them. We stuffed ballot boxes. We shot them. We are not ashamed of it.” Only a tiny number of black citizens were able to successfully navigate the electoral minefield of poll taxes, grandfather clauses, literacy requirements, and vicious brutality; in 1960, 95 years after the 15th Amendment allegedly guaranteed political equality throughout the land, just 6 percent of black Mississippians were registered to vote.

* * *

But after much strife and bloodshed, civil rights finally began to come to Mississippi, giving Mississippi politicians a new voting bloc with which to contend. And yet even after black residents began registering in droves, it was often considered taboo for politicians to actually court their votes. Instead of actually seeking votes with policy proposals that would begin to remediate the stark racial inequities that continued to plague the state, white elites tried the “walking-around money” model I’ve described elsewhere. Like their counterparts in urban areas, white political and economic elites identified those who they believed could gather black votes, often preachers, and paid them to pass out a couple bucks – or, in some cases, food or liquor – in exchange for votes. Defenders of such approaches have argued that these tactics at least provide a benefit to poor voters more tangible than the hollow promises of a television commercial. Unfortunately, such a strategy – treating black voters as a constituency of last resort – is unlikely to foster broader black political progress.

But campaigns aren’t only about fostering a demographic group’s integration into the political mainstream. They’re about winning. Regrettably, the Cochran campaign’s strategy may be misguided on that count as well.

As Carmines and Stimson, Earl and Merle Black, and others have demonstrated, the rise of Southern Republicanism in the 1950s did not begin because of race; indeed, it began among affluent voters in the South’s more cosmopolitan areas and appears to have centered on economic issues. But from the mid-1960s through the 1990s, Southern Republican success became increasingly linked to the Republican Party’s conservative positioning on civil rights and other issues associated with race. It was no coincidence that Barry Goldwater scored easily his highest margin anywhere – 87 percent! – in Mississippi after joining the Southern Senate filibuster and announcing his staunch opposition to the 1964 Civil Rights Act.

That Mississippi history – a history of white Democrats battling to see who could oppose civil rights more strenuously, and then of white Republicans rapidly transforming into a party bastion based on opposition to civil rights – provides an unlikely foundation for Sen. Cochran wooing black voters as a means of winning reelection. For 150 years, Mississippi politicians of both parties have succeeded by essentially persuading voters they will vehemently oppose policies that benefit black residents. And so Cochran’s very prominent African-American outreach – even as he courts a Republican primary electorate that has been bred on decades of Lee Atwater-esque appeals – seems practically schizophrenic: guaranteed to generate a conservative backlash. And inevitably, McDaniel supporters have already seized on the backlash strategy, in a way that has surely embarrassed the authors of last year’s Republican National Committee “autopsy.”

In addition to the likely backlash, the Cochran African-American outreach strategy faces serious logistical challenges. First, the strategy counts on crossover voting in a state whose racial voting divisions are some of the nation’s starkest, with 95 percent of black voters typically favoring Democratic candidates. Second, because Democratic primary voters cannot vote in the runoff, the strategy relies on a very small universe of voters savvy enough to switch parties and vote in a runoff, but not savvy enough to have voted in the recent Democratic primary. Voter mobilization in general is difficult enough without having to cross two separate bridges to make the sale: a partisan bridge and then a turnout bridge. Such challenges require serious turnout machinery – not simply last-minute street money payments to operatives with no track record of being able to pull off such electoral gymnastics.

Much has changed in the 50 years since LBJ signed the Civil Rights Act. But arguably more has stayed the same. It was only last year, for instance, that Mississippi finally ratified the 13th Amendment freeing slaves. As Faulkner once wrote, in the Deep South, the past is never dead – it isn’t even past. The likely reality is that Thad Cochran’s African-American outreach strategy simply requires a departure from too much of Mississippi’s troubled past to succeed.

Today, the planter elites reap what they have sown. Centuries of deploying racism to keep the masses from uniting in populist revolt has finally come due as the accumulation of working-class white racial resentment that elites fomented will prevent them from mobilizing black voters without alienating white conservatives. A bitter pill, indeed, but a twist Faulkner would certainly appreciate.