In June 1965, the British playwright Noël Coward attended a Beatles concert in Rome. He left disappointed, not necessarily in the music, which he couldn’t hear amid the thunderous crowd noise, but in his fellow audience members. In a diary entry written a week later, he was still confounded by the behavior he’d witnessed among the masses:

“I was truly horrified and shocked by the audience. It was like a mass masturbation orgy….To realise that the majority of the modern adolescent world goes ritualistically mad over those four innocuous, rather silly-looking young men is a silly thought….Personally I should have liked to take some of those squealing young maniacs and cracked their heads together. I am all for audiences going mad with enthusiasm after a performance, but not incessantly during the performance so that there ceases to be a performance.”

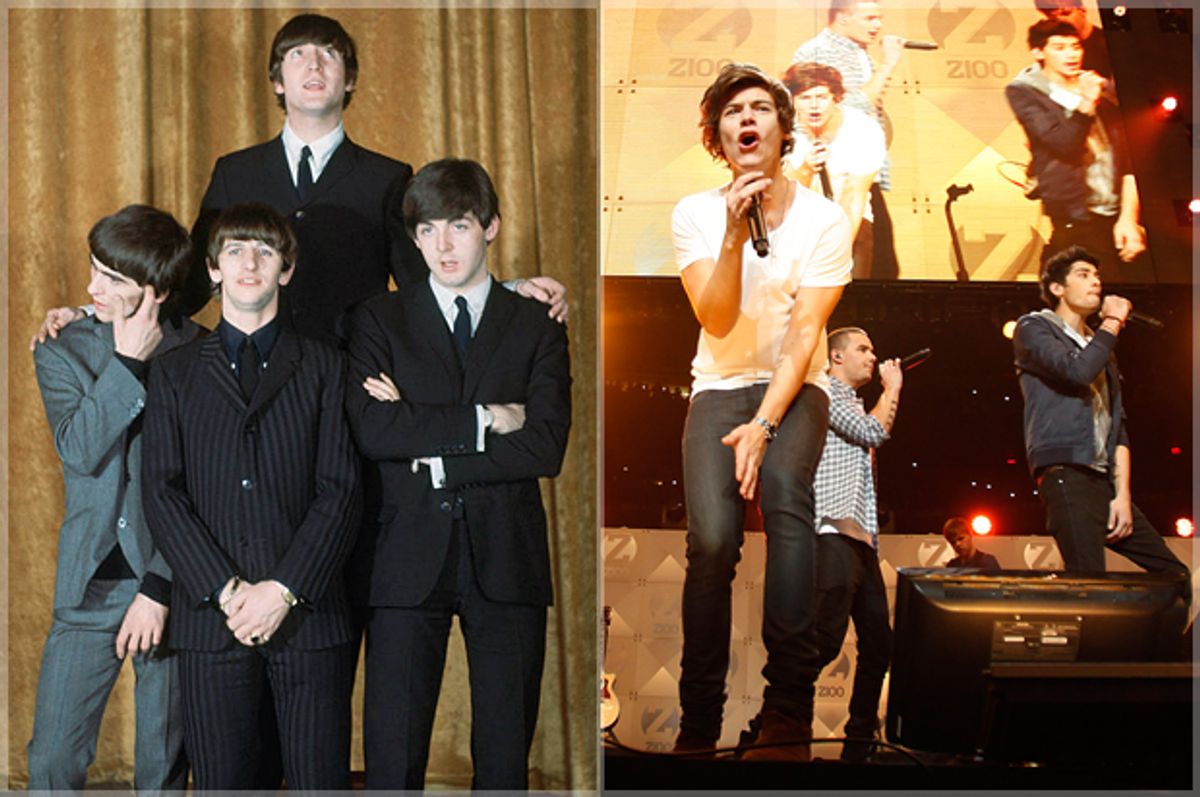

What Coward harrumphed at was the phenomenon known as Beatlemania — that potent alchemy of adoration, hormones and fandom that whipped adolescents into a shrieking frenzy each time one of the Fab Four came within eyesight. Teenagers had swooned over Frank Sinatra’s velvety vocals and Elvis Presley’s swiveling hips, but the hysteria that hounded the Beatles was different — more fervent, almost atavistic, and even dangerous at times.

Beatlemania arguably reached its crescendo during the band’s blockbuster first appearance on "The Ed Sullivan Show" in February 1964, when roughly 73 million Americans tuned in for their five-song repertoire. But to truly appreciate the scope and ardor of Beatlemania you have to turn to their first motion picture, "A Hard Day’s Night," which celebrates its 50th anniversary this month. Shot in seven weeks following the Beatles’ triumphant tour of the United States, "A Hard Day’s Night" is not so much about the Beatles, who play caricaturized versions of themselves (John Lennon remarked that the film is a “comic-strip version of what was going on” with the band), but about Beatlemania itself: the ways it shaped, constricted and occasionally imperiled their day-to-day existence. And it’s this filmic representation of unbridled fandom that continues to exert enormous influence on how emerging pop stars measure and depict their success.

"A Hard Day’s Night" was not intended to be a great film. Shortly after the term “Beatlemania” was coined by the Daily Mirror in late 1963, United Artists approached the Beatles about making an inexpensive feature film to showcase their new songs. By that time, so-called jukebox musicals already had gained a deservedly poor reputation, exemplified by Elvis Presley’s cringe-worthy acting forays. The Beatles were wary of the hackneyed plotlines that these musicals trafficked in. Richard Lester and Alun Owen, the director and screenwriter of "A Hard Day’s Night," came up with a fitting solution: They disregarded plot almost entirely in favor of a pseudo-documentary style that drew out the Beatles’ distinct personalities and witty interactions.

During his first meeting with the group, Richard Lester asked John Lennon if he liked Sweden, where the Beatles had just played a string of concerts. “Yes, very much,” Lennon replied. “It was a room and a car and a car and a room and a concert and we had cheese sandwiches sent up to our hotel room.” This answer greatly informed Lester’s representation of the Beatles. The subtext of "A Hard Day’s Night" is that the Beatles have become entrapped by their success, confined to a series of interchangeable interior spaces broken up only by live performances, mad dashes into chauffeured vehicles, and inane interviews with the befuddled press corps. It’s a glimpse of Beatlemania from the inside — more tedious than exhilarating. The film exposed a central irony of the Beatles: They were always on the move, but their movements were increasingly restricted. They traveled from one exotic locale to another, but each new place looked just like the last.

Lester didn’t need to worry about re-creating Beatlemania on the big screen. The crowds came to him. The film opens with Lennon, George Harrison and Ringo Starr fleeing from actual hordes of fans at a train station. Later, Lester covertly filmed the Beatles gawking from the backseat of a car at the shrieking fans who encircled them. Overall, the movie feels like it takes place in the unstable eye of a perpetually powerful storm. If the Beatles ventured too far from their sheltered spaces, they risked being engulfed by the very forces they helped create.

Lester’s hand-held camera style reinforced the overall sense of claustrophobia. In the opening scenes in the train and hotel room, Lester often holds the camera tight to the Beatles’ faces. In contrast, in the film’s most iconic scene, the Beatles burst out the backdoor of the television studio where they’re rehearsing and discover that the crowds are nowhere to be seen. “We’re out!” Ringo yells in relief. As they rush onto an empty field, Lester switches to a panoramic helicopter shot, underscoring their sudden freedom. The Beatles frolic through the field with childlike joy, almost as if they haven’t been outdoors like this in months. They seem to be burning off all the energy pent up from their programmatic, fishbowl-like existence.

The other significant outdoor sequence occurs when Ringo, egged on by Paul’s meddlesome grandfather, leaves the television studio to reassess his life. As soon as Ringo strolls by two teenage girls, they instantly begin chasing him, the mere sight of a Beatle causing them to depart temporarily from their senses. Ringo ducks into a secondhand store, disguises himself in a trench coat and hat, and then is relieved when a young woman rebuffs his advances. Since seemingly every British teenager was afflicted with Beatlemania, the fact that one had ignored him was proof enough that Ringo had masked his Beatle-ness.

Ringo discovers, however, that he’s rusty at everyday activities. His camera falls into a pond, he nearly stabs a caged bird while throwing darts, and his blundering acts eventually get him arrested. It’s as if he’s become so insulated by the Beatles’ bubble of fame that he’s forgotten how to function outside it. What’s more, he’s lonely without his band mates. Even though he can wander about like anyone else, what he finds is that he’s no longer a normal person. He’s a Beatle, his entire life is structured around being a Beatle, and only his fellow band mates can understand what that entails. In a film otherwise lacking a romantic subplot, the true love story is among the Beatles themselves. When the band reunites at the end for a televised concert in front of a rapturous audience, the Beatles appear overjoyed not merely because they’re performing but because they’re whole again.

Five decades later, jukebox musicals have been replaced by brand-building documentaries and 3-D concert flicks. Nevertheless, the depiction of pop stardom established by the Beatles haunts these productions. In "A Hard Day’s Night," swarming fans and precisely timed operations to shuttle the Beatles to safety are portrayed as vexing parts of their daily lives, hardly commented on by the band. But they’ve since become achievements in themselves, visual markers of superstardom. For ascendant pop artists, it has become requisite to offer filmic proof that they are capable of generating their own mania, matching the bar that the Beatles set. Entrapment, in other words, has become aspirational.

The 2011 documentary "Justin Bieber: Never Say Never," for example, repeatedly cuts to giddy, well-behaved girls waiting for their idol outside Madison Square Garden. They practice their screams and express their devotion to Bieber with earnest lines like: “One day I tweeted him, like, a hundred times.” Later, a nightly news crew reports on the emergence of “Biebermania.” The documentary then flashes to Bieber sprinting through a crowd of shrieking fans, some crying, others expressing concern for his safety.

"One Direction: This Is Us" is more explicit in referencing the Beatles. This 2013 documentary opens with shots of screaming fans converging on the popular British boy-band. “Security was needed to control hundreds of fans,” a newscaster intones. “They call it ‘One Direction mania,’” another says. The documentary then attempts to convey the global scope of the band’s fandom, showcasing crowds of enthusiastic fans across the world. “Even the Beatles never achieved such transatlantic success so early in their careers,” a commentator states. It’s an audacious opening sequence, all but positioning the band as successors to the Fab Four. The parallels continue as the band members are alternately portrayed as ordinary, slightly mischievous post-adolescents and megawatt celebrities whose routine shopping excursions attract massive crowds.

It is not necessarily far-fetched for groups like One Direction to align their image with the Beatles'. After all, perhaps the primary reason that Beatlemania remains embedded in the musical psyche has to do with the overall arc of the Beatles’ career. When "A Hard Day’s Night" debuted, many critics continued to doubt the group’s staying power. United Artists rushed the film into production because they were uncertain if the Beatles would even be relevant the following year. Shortly thereafter, the Beatles transformed from, in the words of Noël Coward, “four innocuous, rather silly-looking young men” into innovative studio musicians. And it’s this last iteration that ultimately gives hope to emerging pop bands. It validates the popular success they built on fizzy songs and provides a blueprint for pivoting to more artistic pursuits afterward. The problem is that the list of groups over the past 50 years that created manias is long (the Monkees, New Kids on the Block, Backstreet Boys); very few could sustain that passion over time or redefine themselves in their musical second act.

As the Beatles learned, whipping crowds into a frenzy sometimes requires nothing more than some killer hooks and a few head shakes. Creating enduring music after the mania subsides is much harder.

Shares