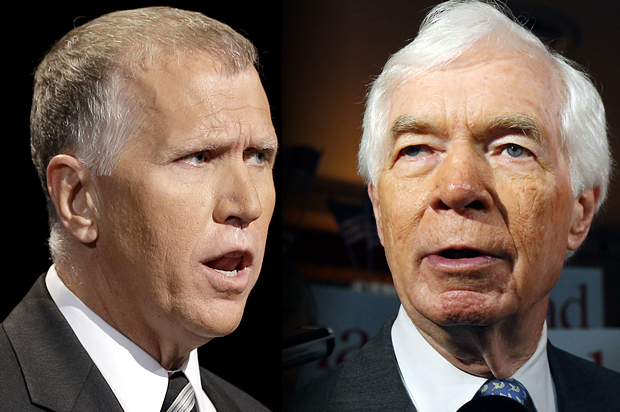

Last month in Mississippi, in an attempt to stave off a Tea Party challenger, Republican Sen. Thad Cochran appealed to African-American voters in his state and won his runoff primary. If Cochran’s successful outreach to African-American voters were replicated by the rest of his party, the political consequences could be significant. But no one should hold their breath.

To get a sense of why Cochran’s effort will not be the norm for the Republican Party any time soon, look at North Carolina’s GOP Senate nominee, Thom Tillis. The state representative recently said African-American and Latino populations were growing faster than “traditional populations” — a comment that not only reeks of racial dog-whistles but also demonstrates a misunderstanding of history.

Tillis’ campaign responded to the ensuing backlash by saying “traditional” refers to groups that have been in North Carolina for a few generations. What his campaign ignores is that its definition aptly describes African-Americans, who have been in the Tar Heel State for more than a few generations, albeit not by their own accord. North Carolina did not have as large a slave trade as neighboring Southern colonies, but by 1767, there were more than 40,000 slaves in the colony with 90 percent of them doing agricultural work. Tillis’ whitewashing of slaves from history has a long tradition. Even the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, the nation’s first public university and called the University of the People, had slaves almost since its inception.

In 1715 slave codes in the early colony prevented slaves from meeting in groups, even for religious ceremonies, and from leaving their master’s properties, and required slaves to carry a ticket whenever they left the plantation. In the 1800s, laws were so restrictive that runaways were forced to wear iron collars when hired out and even free black men were forbidden to preach and slaves were forbidden to learn how to read and write by other slaves. Because they were not considered part of the white power structure, African-Americans could be disregarded as pure property and not as humans.

Of course, the end of slavery was not the end of the injustices faced by African-American North Carolinians. Under Jim Crow laws, blacks and whites were forbidden from exchanging textbooks. After the decision of Brown v. Board of Education, North Carolina’s Legislature tried to work around integration through a plan that recommended the state consider applications to pay private school tuition grants to parents of children assigned to integrated schools.

Perhaps most disturbing, though, was the amount of forced sterilizations African-Americans went through in the state. According to the Charlotte Observer, between 1955 and 1966, 80 percent of the people sterilized in Mecklenburg County, where Charlotte is located, were African-American under the auspices that living conditions were so poor in low-income neighborhoods.

It is in this context that Tillis’ remarks must be understood. He is excluding African-Americans from the narrative because they aren’t part of who he generally thinks of as belonging in the state.

The political advantages of appealing to all races is not lost on Republicans, however. The same week these comments came out the Republican National Committee announced the launch of the North Carolina Black Advisory Board to reach out to African-Americans in the state. The problem is that merely “reaching out” isn’t sufficient; there needs to also be a substantive record or appreciation of policy needs. Unlike Cochran, who could point to his support for Historically Black Colleges and Universities and more moderate stance on food stamps, Tillis’ policies are actively trying to disengage those he sees as “nontraditional.” From slashing unemployment benefits in the state with the fourth-highest black unemployment rate, to repealing the state’s Racial Justice Act, which allowed inmates to challenge death sentences on grounds they were discriminated against based on race, Tillis has shown he doesn’t regard African-Americans’ needs as “traditional” needs for North Carolina.

As speaker of the House in the N.C. General Assembly, he oversaw passage of a law that not only requires voters show a photo ID but also cut the amount of early voting days by a week while expanding use of absentee voting, typically used by Republican voters. A study by Democracy N.C., a nonpartisan good government group, showed 70 percent of African-Americans who voted used early voting. By carrying out these measures, Tillis shows he is not sincerely interested in engaging with African-American or Latino voters, who are increasingly becoming an important part of his state’s fabric, but wants to create a new “tradition” of disenfranchisement.

Sadly, it is Tillis, not Cochran, who is in the mainstream of his party. And for that reason, the success of the latter is not likely to be replicated in significant numbers any time soon.