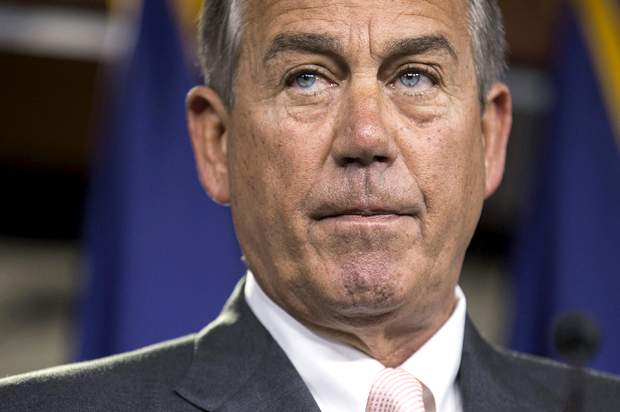

It’s getting more and more difficult with each passing day to view John Boehner’s long-shot lawsuit against Barack Obama as anything but a ridiculous political stunt. Boehner’s own arguments for suing the president are illogical and it’s impossible to escape the fact that he’s trying to force implementation of a law he wants repealed, but there was always a chance that backers of the suit would try and put together a coherent case for why it should be taken seriously. That apparently was too much to ask as well.

Boehner’s suit began its slow march through the legal system today as the House Rules Committee convened a hearing to deliberate the matter and hear testimony from a panel of constitutional lawyers. In practice, the panel testifying before the Rules Committee was equally divided: two legal minds in support of the lawsuit, two against. On paper, however, the split wasn’t quite so equal.

Jonathan Wiesman of the New York Times reported earlier today that one of the witnesses testifying in support of the House’s ability to sue the president, law professor Elizabeth Price Foley, wrote an Op-Ed for the Daily Caller just few months ago arguing that Congress cannot sue the president because it does not have standing. She was unambiguous about it, and specifically cited Obama’s move to delay enforcement of the employer mandate – the exact issue she’s now arguing the House has standing to sue over:

When a president delays or exempts people from a law — so-called benevolent suspensions — who has standing to sue him? Generally, no one. Benevolent suspensions of law don’t, by definition, create a sufficiently concrete injury for standing. That’s why, when President Obama delayed various provisions of Obamacare — the employer mandate, the annual out-of-pocket caps, the prohibition on the sale of “substandard” policies — his actions cannot be challenged in court.

So the pro-lawsuit side weren’t just arguing against precedent and established legal principles, they were arguing against themselves.

And they’re also apparently basing their argument on a legal fiction. Ian Millhiser, the senior constitutional analyst at the Center for American Progress, dove into a Politico piece written by Foley and attorney David Rivkin justifying the suit, and he found that “a major prong of Rivkin and Foley’s legal argument rests on an egregious misreading of a famous Supreme Court case.”

If these were the only embarrassments for the pro-lawsuit faction, then their day would have been bad enough. But they’re also catching rebukes from key Republicans. After Boehner said last week that immigration reform was officially dead for the year, Rep. Mario Diaz-Balart took a swipe at his own leadership by arguing that the best way to curb the threat of Obama’s executive action on the matter was to actually pass legislation – an implicit rejection of the rationale behind Boehner’s lawsuit.

And yesterday, during a speech at Hillsdale College, Rep. Paul Ryan offered his own thoughts on asking judges to intervene in political fights:

Finally, there is the temptation to ask courts to intervene and solve our problems for us. Some conservatives think of judges the way Progressives think of bureaucrats: technical experts with the solutions to our constitutional conflicts. But judges, like bureaucrats, are often the problem. We must be mindful of this temptation. It is true that the Supreme Court can be an ally in conflicts surrounding the Constitution. But it can also be an adversary. Under our Constitution of self-government, the court that really counts is the court of public opinion. We can’t simply rely on the Supreme Court alone to defend our rights. We have to remember that at the end of the day the court of public opinion, where the American people hand down their verdict on Election Day is the final arbiter. In popular government, the people are the final judge and jury.

None of this, of course, will stop Republicans from voting to approve the suit. It’s clear that victory in court is not the endgame and never was. It’s always been about riling up conservatives ahead of the election by sticking it to Obama.