In April of 2014, the National Museum of Natural History in Washington closed the doors of its paleontology hall. Gone were the placoderm fish, the Ice Age mammals, the hollow-boned pterodactyls. Gone especially were the dinosaurs – the Apatosaurus, Tyrannosaurus and other kings of the primordial earth.

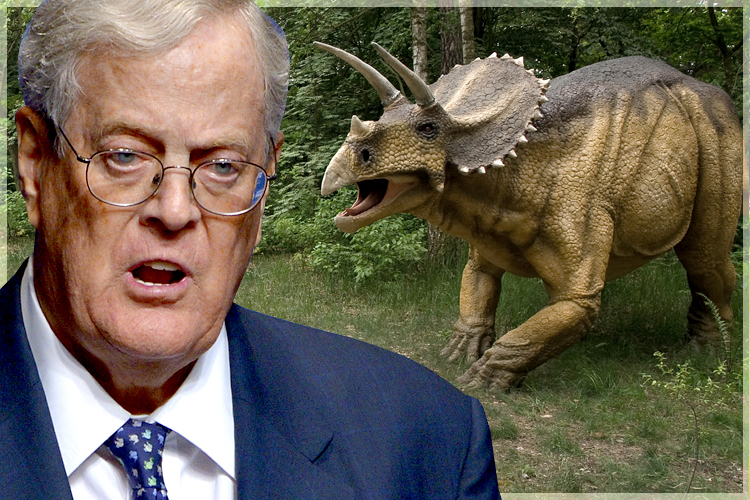

But this was no second extinction. It was evolution, a $45 million renovation project that would expand the paleontology halls to 25,000 square feet and give an outdated series of displays a desperately needed update. $35 million of that cost – the largest single gift in the museum’s history — was pledged by one David H. Koch.

Nobody inspires more liberal anger than Charles and David Koch. As owners of the massive Koch Industries, a multinational energy and manufacturing conglomerate, the Koch brothers have spent a fortune bankrolling a profusion of right-wing causes. They have gained a well-deserved reputation as climate change deniers, polluters, union busters and all-round rapacious capitalists. Trace most conservative campaigns back far enough, and you’ll find them at the other end, pumping their libertarian vision into the body politic.

That’s business, however. Everybody needs hobbies, and one of David Koch’s biggest hobbies, beyond his more general philanthropic pursuits, is paleontology. He has toured museums all over the world, visited dig sites in Central Africa, and funded the excavations of Don Johansen, the discoverer of the famous prehuman fossil Lucy. In an interview with the magazine Archeology, Koch excitedly recalled pulling hominid bones from the ground at Johansen’s dig site in Olduvai Gorge. He keeps a frame replica of Lucy’s hand as a trophy on his office wall, and in 2009 he funded the somewhat controversial Hall of Human Origins at the Smithsonian to the tune of $15 million.

But judging by his public statements and the size of his bequests, dinosaurs are the things that interest him most. Koch caught the dinosaur bug at the age of 14, when his father took him and his twin brother, Bill, to visit the American Museum of Natural History. “I was just dazzled by the dinosaurs,” he told the AP. He went further in an official statement to the New York Times where he said that he was “blown away and just fascinated by their enormity.” After funding a complete redesign of the AMNH dinosaur halls, he began looking at the increasingly outdated Smithsonian exhibits with a speculative eye. The opportunity to fund the renovations to the paleontology hall, he said, “was in my sweet spot. It [was] such a thrill that it’s almost a gift for me.” Appropriately enough, the announcement was made on his 72nd birthday.

This interest in paleontology may seem surprising, considering the Koch brothers’ funding of climate change denialists and Tea Party groups. But while the socially conservative leanings of the Tea Party have led to several attempts to undercut the teaching of evolution, oil companies like Koch Industries have never had much patience for the idea of creationism. They make their money from the daily business of rock strata and fossil fuels, the kind of practical geological work that leaves no doubt about the age of the Earth. In the Archeology interview, Koch spoke about young earth creationists with a kind of bewildered disdain. He had nothing but kind words for Darwin.

Koch is not the first tycoon to take an interest in dinosaurs. Throughout American history, paleontology has drawn much of its funding from private sponsorship instead of government support. George Peabody, the father of modern philanthropy, spent $150,000 establishing the Peabody Museum of Natural History at Yale in 1866. He also bankrolled his nephew, Othniel Marsh, during his fierce public struggle with rival paleontologist Edward Cope. For both men, the object of the contest – what would be later called the Bone Wars — was to show up the other by discovering the most dinosaurs. As with all wars, the side with the deepest pockets won, and nobody in paleontology had deeper pockets than Marsh.

That changed when Andrew Carnegie arrived on the scene. The great steel baron had an eye toward establishing a museum of his own in Pittsburgh, and for that, he needed dinosaurs. For a while he publicly prodded the now-aged Marsh about donating some of his dinosaurs, but Marsh sidestepped the request by dying. Frustrated, Carnegie turned to the direct method. He funded a series of expeditions to the American West, instructing the scientist to bring him back the biggest dinosaur they could find. They eventually returned with the 85-foot skeleton of the sauropod Diplodocus (a genus that Marsh himself had described), which was rapidly declared a new species and named in honor of Carnegie. Various heads of state from Europe came calling, hoping for a dinosaur of their own, and Carnegie obliged them by selling them plaster casts of his Diplodocus.

Carnegie once boasted to Marsh that he could devote $50,000 a year on paleontology, an amount that translates into nearly $6 million today. For several decades after World War II, though, spending that kind of money on dinosaurs went out of style. Grand expeditions captained by dashing paleontologists were a thing of the past. Dinosaurs came to embody failure in both the public and scientific spheres, suitable only for children. That lull persisted until the 1980s, when the Dinosaur Renaissance radically changed the public understanding of prehistoric animals. Gone were the tail dragging, swamp-bound failures. In their place sprang the fast, active, ferocious dinosaurs of “Jurassic Park,” and with that revival of interest came a flood of funds.

Today, the kind of giving Carnegie pioneered has been easily matched, and not just by David Koch. The Duncan family, a trio of oil billionaires, beat Koch at his own game by partially funding a 30,000-square-foot, $85 million paleontology installation at the Houston Museum of Natural Science. The exhibit came complete with more than 60 huge skeletons and curation by the famed paleontologist Robert T. Bakker. Not to be outdone, an Australian mining magnate named Clive Palmer threw the media into a tizzy last year by investigating the possibility of cloned dinosaurs for his resort in Queensland. Upon being informed that this was not just unwise but impossible, Palmer settled for building the world’s largest robotic dinosaur park instead.

There are a few different facets to this wave of billionaire support for paleontology exhibits. Dinosaurs make for cool toys, an impulse that holds whether the toys are made of crudely painted plastic or elaborate resin casts. There’s nothing like a toothy skeleton — or a hall full of them — to sweeten the already tempting social benefits of philanthropy.

But there’s one other important aspect to dinosaurs: They’re layered with symbolic weight. Dinosaurs are potent metaphors for many things, some of them contradictory: age, obsolescence, the childhood love of monsters. But more than anything, dinosaurs symbolize something invulnerable and earth-shaking. In the aftermath of the Dinosaur Renaissance, they have burnished that invulnerability with an aura of speed and power. To look up at a Tyrannosaurus rex now is to be struck with a visceral sense of evolution at its most irresistibly murderous: “survival of the fittest” writ very, very large.

That ethos — that size, ferocity and dominance justify themselves — is one that free market ideology has embraced with an alarming zeal. It colors the love of dinosaurs that Koch and his fellow billionaires share. And if it seems reminiscent of another evolutionary philosophy — social Darwinism — that’s not an accident.

Perhaps the classic example of this lies in the writing of Andrew Carnegie. The manufacturing magnate considered himself a disciple of a contemporary scientist and philosopher named Herbert Spencer, who at the time was one of the foremost writers about evolution. It was Spencer, not Darwin, who coined the phrase “survival of the fittest,” and he was a vocal proponent of the idea that natural selection was all-encompassing. Just as there were different species of animals, he wrote, so there was a natural, class-based division of labor among humans. In his 1851 text “Social Statistics,” he argued against devoting resources to the weak, the unskilled or the poor. It was better for society and the species as a whole to let them die.

Spencerian evolution was a philosophy tailor-made for the Gilded Age, and Carnegie championed it with vigor. He embraced the laissez-faire elements of Spencer’s work, viewing them as both a justification and a blessing of his own monopolistic practices. Carnegie fiercely fought against any kind of government regulation of commerce, and used evolutionary theory to excuse his ferocious treatment of unions. He could not quite bring himself to agree wholeheartedly with Spencer, however; he himself had come from a poor background, and he had a jaundiced view of inherited wealth in business. The great businessmen should arise from the ranks of the poor, he wrote, and natural selection would weed out those who could not make it. But at the same time, he pushed for the idea that it was the responsibility of the wealthy to fund things they deemed to be worthy causes. For Carnegie that meant giving the majority of his income to libraries, parks, museums and dinosaurs.

Those positions would all be familiar to David Koch. Spencer’s conception of evolution justifies and encourages free market capitalism and economically conservative thought, with its scorn for the poor and any government programs that might try to help them. In the world of the right, a magnate’s wealth is a sure sign of his well-deserved evolutionary success. Perhaps that is why dinosaurs are so enticing to the wealthy: If you believe that only the strong should survive, well, what’s stronger than a dinosaur? The roaring theropod, the adaptable raptor and the mighty sauropod are all perfect symbols for the kind of dynamic, powerful and successful entities that businessmen believe themselves to be. Most people look at a dinosaur skeleton and see a strange, magnificent animal. When Koch, or Carnegie, or any other magnate looks at a dinosaur, perhaps they also see a capitalistic totem of overwhelming success. And success, more than anything, deserves money.

The ironies here are hard to overstate. The first is that healthy ecosystems do not, by and large, have monopolies, something dinosaur paleontology bears out. In his landmark “The Dinosaur Heresies,” Bakker (curator of the Houston exhibit) noted a curious phenomenon: At the end of the Cretaceous, there was only a handful of big dinosaurs appearing in the fossil record, as opposed to the wild profusion that had prevailed for much of the Mesozoic. He described it as the sign of an ecosystem under real stress. Tyrannosaurus and its hyper-specialized relatives appeared successful, but success in a specialized field is only a short-term benefit. When conditions change rapidly, those best adapted to the former world tend to fall the hardest.

It is also worth noting that, while an asteroid strike sparked the great extinction event at the end of the Cretaceous, what really drove it to its murderous conclusion was the environmental chaos of the resulting sudden shift in climate. It was a shift that most lineages of dinosaurs could not withstand. And it was a shift not dissimilar to the one bearing down on us now, helped along by Koch businesses, pipelines and lobbying efforts.

The last thing that dinosaurs embody, perhaps more even than success, is extinction. For all their size, for all their strangeness and power, the world changed too quickly and substantially for them to survive. When David Koch strolls through the new Smithsonian exhibit in 2017, he should probably keep that in mind.