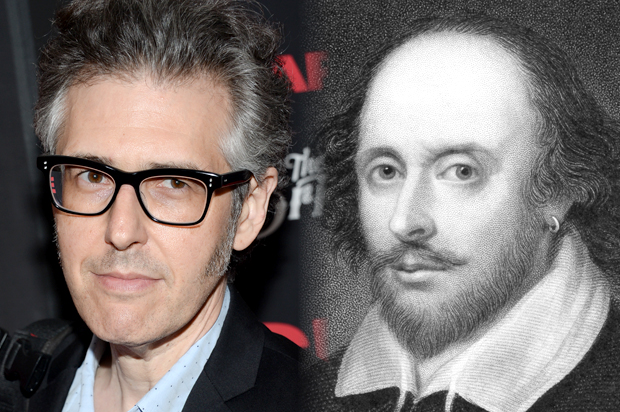

Maybe it’s a watershed moment when the smartest guy in public radio lets slip the dogs of his inner Cartman. Where were you when Ira Glass tweeted that “I think I’m realizing: Shakespeare sucks?”

Shakespeare is having a hell of a summer. More Americans probably know “The Fault in Our Stars” than know the fault is not in our stars but in ourselves. And now this.

The backlash was swift. The New Republic called Glass a philistine, and the New Yorker’s Rebecca Mead – although mostly concerned with Glass’ repeated use of “relatability” as a criterion Shakespeare failed to meet — wrote that “the Bard of Public Radio expressed himself like a resentful millennial filling out a teacher evaluation.” Glass walked his anti-Shakespeare tweets back. The first of them is gone from his feed. For the record it was: “@JohnLithgow as Lear tonight: amazing. Shakespeare: not good. No stakes, not relatable. I think I’m realizing: Shakespeare sucks.”

John Waters once told David Letterman he had a friend in prison. “How long will your friend be incarcerated?” asked Dave. “Oh, life,” said Waters. Letterman: “So more than a traffic violation?” “Everybody has a bad night,” said Waters.

On that basis, we can dismiss most of the charges against Glass. In the last quarter-century, nobody has provided a better answer to the question, “What else can radio do?” From the 20-minute (swallow hard) “relatable” human dramedy to the full-hour “deep dive” (a phrase to which we will return), “This American Life” has earned its spot in the public radio penthouse. When it’s good, it’s as good as radio gets.

Which is why you want Glass to have a different reaction to Lear. You want him to say, “Hey, I didn’t really get that. Maybe we should do a whole show about King Lear. We could ask Sam Waterston to go up to people in the street and do the ‘Come, let’s away to prison’ speech. And the relationship between a king and his fool, that’s a segment! Hey, we already call them Act I, Act II, etc.”

What is meant by “relatable”? “House of Cards” is basically “Richard III,” right down to the trope of the villain addressing the audience; but it’s relatable because it’s not period or linguistically complex or otherwise difficult. Relatable means easy to digest. I worry about our drift toward idiocracy. I worry about a dystopian and stupid future in which there is nobody willing to do the intellectual heavy lifting except four people hiding in the offices of the New York Review of Books.

In fact, you know what’s in decline? Depictions of our dystopian and stupid future! “Divergent” and “The Hunger Games” are not as good as “Fahrenheit 451,” Walter Tevis’ overlooked “Mockingbird” (the best book about a future in which nobody can read) or “Brave New World” (whose moral axis is a “savage” schooled exclusively on the Complete Works of Shakespeare. Just sayin’). Think about that. Our future is so hollow that we’re losing the capacity to imagine its hollowness.

In 2014, the mortal sin is being boring or difficult. Keep it light. The physical front page of last weekend’s New York Times Sunday Review section is almost entirely given over to a guy’s essay about his cat.

The National Geographic Channel is currently airing a three-part documentary about the ’90s narrated by Rob Lowe. Cue your snarky joke: “What do they have – James Van Der Beek talking about the Gulf War?” Yes. They really do. They have James Van Der Beek talking about the Gulf War.

That phrase “deep dive” is so overused we may have to retire it; but the reason it (and “long-form”) have become so necessary is because the default settings for our culture are shallow and short. Deep dives used to be just dives. Now they’re special because they’re deep. We mainly prize information that’s short, easily transportable and peppily conveyed. The perfect symbol of this is the TED talk, predicated on the notion that no idea is so complex that it can’t be presented in 18 minutes. Really? That’s so long! Can’t they all just be funny GIFs and Vines? (Note to self: Write “Richard III’s TED Talk” and send to Shouts & Murmurs.)

Public radio is supposed to be some kind of French Foreign Legion garrison against the drift toward idiocracy; but we’re – I work in public radio – struggling to overcome the chronic perception that we‘re boring. So we keep bleeding a little more laughing gas into the line, a little more content that’s putatively entertaining and faster-paced. “Here and Now,” the national afternoon show, is basically CNN with no pictures.

I do not exempt myself. I host a daily show. We do work that I never have to apologize for – recent shows on the evolution of Germany’s postwar psyche, on the modern viability of ancient notions of hell, and a hard-to-explain episode on people who can never communicate through any language at all – but sometimes I look at subjects being undertaken at my own instigation and I hear voices singing, “Tonight, let it be Middlebrau.”

The most alarming public radio content is the stuff pitched at millennials. A weekend show called “Ask Me Another” plays like a massive clandestine Rand Corp. study of how dumb a question has to be before a 2014 hipster, slouching toward Brooklyn, would absolutely be able to answer it. They’ve done such things as telling contestants the answer is embedded somewhere in the question: “Before starting his influential company, this technology pioneer, with this last name, held jobs designing Atari games and entertaining children while dressed as the Mad Hatter.” Last week, part of one segment involved bleating out animal noises. “How does a rooster go?” was not the lay-up it should have been.

So it’s not the Ira, it’s the era. In fact, I’d like to see more Glass, not less. He might be the guy to nudge us back in the other direction if the recent round of face-slaps calls him to his senses. Now I really do want to hear him do a Shakespeare show. Imagine that oddly comforting nasal voice saying, “Act I. Where the bard sucks, there suck I. Contributor Mike Birbiglia visits Harold Bloom.”