I bought a pair of Air Jordan sneakers recently. That’s not the whole truth. I bought two pairs of Jordans last month, which brought the total to five for the year. I’m going to buy (at least) one more pair this month, and a few more before 2014 ends. In other words, I have and will continue to spend entirely too much money on some fucking sneakers.

I’m not a collector. I’m more interested in my own vanity than impressing sneakerheads with a closet full of shoes. But I’m not out there buying just any shoes. I’m drawn to Jordans in a way that almost makes other shoes invisible to me. They are legend.

Take my most recent pair, the Wolf Grey Jordan 3’s. The colorway is new, but the Jordan 3 debuted in 1988, the year Michael Jordan’s legend was cemented. In his fourth year in the NBA, he led the league in scoring, averaging 32.5 points per game, as well as steals, won Most Valuable Player and Defensive Player of the Year, on top of winning the slam dunk competition. The design of the shoe is almost secondary; it’s cool to feel a connection to such greatness.

That’s what I’m really buying when I get a new pair of Jordans: cool. It’s not something I come by naturally. Ask all the people I went to high school with who didn’t even bother to invite me to our 10-year anniversary that took place a couple of months ago. Ask the kid from the after-school program I used to volunteer at whose first words to me were “you corny.” Ask anybody, really. The Mychal Denzel Smith brand is not synonymous with cool.

Not the case for Michael Jordan. During his playing career, Jordan epitomized cool. In particular, he became the standard bearer of black masculine cool. He gave us the shaved head, the wagging tongue, the baggy basketball shorts, the effortless fadeaway and, of course, the sneakers. Growing up, I, like millions of others, wanted to be like Mike, and found whatever way I could to emulate his swagger. I’m naturally awkward and I never quite got it right, but purchasing those kicks at least made me feel like I had a chance. You have the ability to possess the cool they exude and maybe isn’t innate to your own character. They’re a status symbol more than anything.

I shouldn’t be as concerned with “cool” at this point in my life, but we all have our flaws. And the type of cool associated with Jordans represents something complicated for me. There’s a connection to a certain variety of black masculinity, one inseparable from America’s troubled relationship with black men. It’s not that different from the obsession with hip-hop. Putting on a pair of Jordans is like being able to wear Jay Z lyrics. It’s the kind of cool that has kids who have never seen Jordan play standing in line for hours just to feel it.

Personally, I like the feeling of invincibility that provides. But then I remember that that cool has never protected us. As much as America steals from our culture, as much as they copy and commodify black male cool, we’re still expendable. I remember Michael Brown and my Jordans don’t feel all that cool anymore. They feel like an expensive placebo of progress.

Still, I’m going to buy another pair.

I’ve also thought about buying some LeBrons, but I haven’t made that commitment just yet.

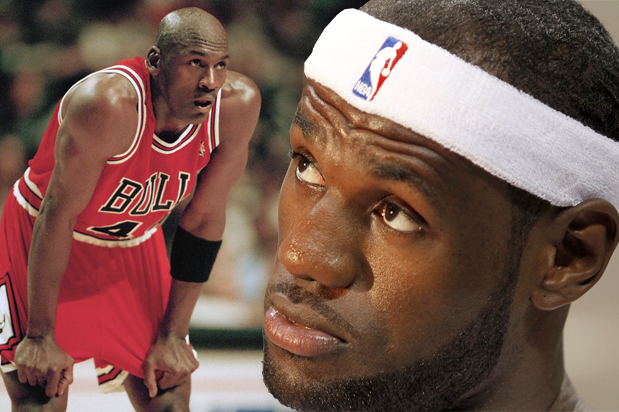

It’s not really fair to keep comparing LeBron James to Michael Jordan. He should be allowed to chart his own path absent any questions of “What Would Jordan Do?” And that’s exactly what he’s done. And that’s also why his sneakers aren’t as cool.

Don’t get me wrong, those LeBron 11’s are pretty hot. But it’s not the $200 (or $275 for the LeBron 11 Elite) that’s stopped me from buying them. LeBron, his brand, and his shoes just don’t have that “it” factor. Most popular athlete on the planet notwithstanding, something is missing. He hasn’t given us a wagging tongue. The King James crown doesn’t have the iconic feel of Jordan’s Jumpman. His post-game interview fashion show has been usurped by guys not much younger than him. His hairline is the thing of vicious (and hilarious) jokes, not emulation, and he can’t lay claim to headbands or arms full of tattoos (thanks, Allen Iverson). “Witness” my stick around, but it’ll never top “Air Jordan” or “I Wanna Be Like Mike” or “Is it the shoes?!” By traditional metrics, LeBron has no cool. He’s no Jordan.

Which is great. I’m glad LeBron isn’t Jordan. We don’t need another one. We need LeBron.

Jordan owns cool, but LeBron’s legacy will be much more important. It started with the infamous “Decision” in 2010. Putting aside the grandiose hour-long TV special and the hurt feelings of Cleveland Cavaliers fans, “The Decision” marked an understanding for a new generation of athletes of their power. It showed that LeBron doesn’t see himself as an employee beholden to the whims of ownership and management — he controlled his own future. He could decide where to play, whom to play with, and (within the structure of the NBA’s collective bargaining agreement) how much to play for. He assessed his own worth and only agreed to play on terms that honored that.

In the aftermath, when he caught backlash for it, he didn’t shy away from talking about the role race played in the reception of “The Decision.” He took heat for daring to be a 25-year-old black man who would not demur in the face of white male ownership, and he didn’t back down from saying so.

In 2012, in the wake of the killing of Trayvon Martin, he organized the entire Miami Heat team for a photo that still gives me chills. They collectively donned their hoodies, bowed their heads, and LeBron captioned the photo on Twitter with “#WeAreTrayvonMartin” and “#WeWantJustice.” Who ever heard of Jordan doing something like that?

Earlier this year, who was the first NBA player to speak up in the wake of the Donald Sterling tapes and call for his ouster from the league? None other than LeBron James. Rumors circulated that he would lead a player boycott for the 2014-15 season if Sterling wasn’t removed as an owner, and while they were just rumors, it wasn’t hard to believe LeBron might actually do it.

And most recently, with “The Decision Part II,” he decided to return to the Cleveland Cavaliers. Why? Why would he go back to play for Cavs owner Dan Gilbert after the paternalistic and insulting letter he wrote in response to LeBron leaving in 2010? In LeBron’s own words, published by Sports Illustrated:

I feel my calling here goes above basketball. I have a responsibility to lead, in more ways than one, and I take that very seriously….I want kids in Northeast Ohio, like the hundreds of Akron third-graders I sponsor through my foundation, to realize that there’s no better place to grow up. Maybe some of them will come home after college and start a family or open a business. That would make me smile. Our community, which has struggled so much, needs all the talent it can get.

It echoed his Finals MVP speech from 2013 when he said, “I’m LeBron James, from Akron, Ohio. From the inner city. I’m not even supposed to be here.” He thinks beyond basketball. He thinks beyond Gilbert. He takes his fame and the responsibility that comes with it seriously. He’s a black boy who got a chance and he wants to ensure that others like him get a few chances, too.

That’s not MJ cool. Jordan just wanted to play ball and sell sneakers. He couldn’t be bothered with caring about the world around him. LeBron wants to play ball and sell sneakers, as well, but he’s also an engaged citizen with a sense of purpose that extends beyond his stat line. As a result, he doesn’t represent the kind of black male cool that we’re used to.

This isn’t a screed meant to denigrate that kind of cool. I’m in an endless pursuit of it, hence the exorbitant amount of money spent on Jordans. It’s also not a coronation of LeBron James as the next great athlete-activist. He isn’t Jim Brown, or Muhammad Ali, or John Carlos, or Tommie Smith, or Kareem Abdul-Jabbar. He’s LeBron. He wants to be the first billionaire athlete. But that doesn’t mean he’s turning his back on the world.

Twenty years from now, I’ll probably still be buying new Jordans. They’re classic. I doubt LeBron will have any classic sneakers. I’ll gladly eat my words if that’s not the case. But 20 years from now, we’ll also be asking, “Who is the next LeBron?” and it’ll mean more than what this person can do on the court or his status as a global icon. He’ll have to produce a legacy that touches people’s real lives. That’s pretty cool.