A few days ago I wrote about the Hack Gap – the imbalance of conservative and liberal pundits who will unquestioningly fall in behind partisan crusades in order to achieve a common political goal – and how it had found renewed expression in the D.C. Circuit Court’s ruling in Halbig v. Burwell. Two judges on a three-judge panel ruled that one imprecisely worded line in the Affordable Care Act invalidated subsidies for customers purchasing health insurance through federal health exchanges. Since 36 states defaulted into federally run exchanges, the judges had essentially ruled that the ACA was to be blown up from within.

Conservatives fell immediately in line behind the ruling and praised both its strong reasoning and strict adherence to the law. Where gaps in reasoning or historical conflicts popped up, they simply rewrote the history or ignored it altogether. Obamacare was always doomed to fail like this, they insisted, even if no one knew it until now.

It’s simple enough to observe this phenomenon as it happened, but explaining why it happened is a bit trickier. New York Times legal writer Linda Greenhouse offered a glimpse into the conservative anti-Obamacare pathology yesterday in her column tracing the roots of the legal challenges to the Affordable Care Act.

Greenhouse revisits a December 2010 conference held at the American Enterprise Institute, in which AEI scholar Michael Greve offered this assessment of the ACA:

“This bastard has to be killed as a matter of political hygiene. I do not care how this is done, whether it’s dismembered, whether we drive a stake through its heart, whether we tar and feather it and drive it out of town, whether we strangle it. I don’t care who does it, whether it’s some court some place, or the United States Congress. Any which way, any dollar spent on that goal is worth spending, any brief filed toward that end is worth filing, any speech or panel contribution toward that end is of service to the United States.”

“Hygiene” was, as Jonathan Chait writes, an interesting choice of words in that it treats the Affordable Care Act – a law designed to promote access to healthcare – as a contagion or disease. It’s a viewpoint that is fairly common among conservatives, from radio hosts to cable news to Tea Party rallies. Thom Tillis, the Republican candidate for Senate in North Carolina, says on his issues page that “ObamaCare is a cancer on our national economy.” Viewed through that lens, expunging it is the only responsible thing to do. It also prevents one from acknowledging that the law is actually doing something to benefit the life of the average American. No one reacts to a cancer diagnosis with a resigned shrug and the hope that some good might come of it.

I think there’s also a widespread understanding on the right of the massive political threat they face. Ceding healthcare reform to the Democrats is huge. There are few political issues that carry more moral weight than healthcare, and if the Democrats successfully legislated their way toward making it more accessible and less of a financial burden, that would spell big trouble for conservatives and the GOP down the road. When Obama came to office and made his healthcare plan (borrowed from Republicans) a priority, the GOP had a choice: get on board with reform, propose some policy tweaks and share the political windfall; or fight reform to the death and trust the whole thing would fail, leaving them no worse than when they started.

The mentality voiced by Greve meant they had no choice but to bet big on the latter. And they came close to derailing the whole enterprise a couple of times (Sen. Scott Brown, the 5-4 ruling in NFIB v. Sebelius). Once Obamacare was implemented, though, the game was largely over.

But again, when you view the law as a disease, a cancer, there is no giving up. And so when two judges gave the right a thin ray of hope by straining legal reasoning to the breaking point, conservatives jumped on it and put all their faith into Halbig. That’s why you see them doing silly things like argue that the case is not important enough to warrant a hearing before the full D.C. Circuit Court (which the Obama administration has requested), even though the impact of the ruling would be to literally put people’s lives at risk by denying them access to health coverage. The “political hygiene” of the matter is thus placed above the moral considerations. “For this politically driven crowd to claim the moral high ground in preemptively accusing others of playing politics borders on fantasy,” writes Greenhouse.

The refusal to see any good in the Obamacare disease also helps explain why it is that the party of “repeal and replace” can’t seem to figure out the “replace” part of the mantra. For all the caterwauling about the Affordable Care Act’s big-government socialist takeover of the health industry, it’s actually a pretty conservative plan. And Republican policymakers who’ve been trying to craft Obamacare alternatives find themselves stymied by the fact that pretty much everything they churn out ends up looking like Obamacare.

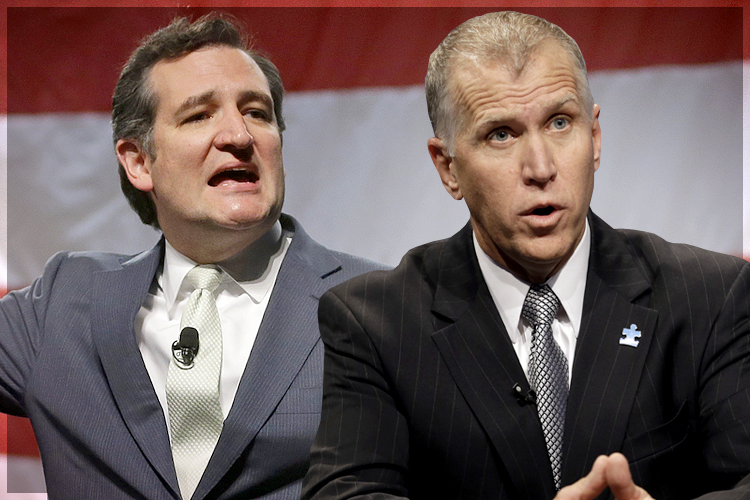

Some conservative health policy wonks, like Avik Roy, are trying to convince conservatives that they can “replace” Obamacare while still keeping large chunks of it, like the federal tax subsidies that Halbig says are invalid. That argument isn’t going to fly with Tea Party lawmakers like Ted Cruz, who celebrated the D.C. Circuit Court panel for shielding “citizens from Obamacare’s insidious penalties, mandates, and subsidies.” Meanwhile, pro-repeal Republican candidates on the campaign trail are struggling to balance visceral conservative hatred of the ACA with the practical realties of what repeal would actually mean for people currently benefiting from the law.

If the ACA survives this round of legal challenges – never a safe assumption, given the demonstrated willingness of conservative justices to subordinate legal reasoning to ideology – then conservatives may finally be forced to resign themselves to the fact Obamacare will never fully be gone. But there’s an excellent chance they’ll keep treating it like a disease and rallying around whatever long-shot “cure” they can dream up next.