In mid-August, the Chicago Tribune published a poll showing that Karen Lewis, the outspoken president of the Chicago Teachers Union, was leading Rahm Emanuel, 43 percent to 39 percent, in a hypothetical 2015 mayoral race.

Lewis led a 2012 strike after Emanuel tried to impose longer school days with no pay increases (she got her teachers a raise), and vociferously opposed the closing of 50 schools, which were mostly in black neighborhoods. During a pre-strike rally, she called the mayor “a liar and a bully.” Emanuel returned her contempt, shouting “Fuck you, Lewis!” during a tense private meeting. Lewis recently filed papers to raise money for a possible run against the man she labeled “the murder mayor,” because of Chicago’s high crime rate, and she has a pledge of $1 million from the American Federation of Teachers.

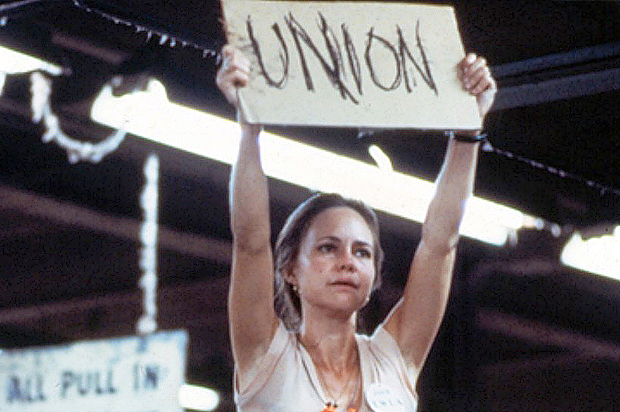

If Lewis wins, or even mounts a credible campaign, she will become the most prominent labor leader in America. In that role, she’ll be an appropriate successor to John L. Lewis, Jimmy Hoffa and Walter Reuther, those crusty avatars of mining, trucking and manufacturing. As an African-American, a woman and a professional (she has a sociology degree from Dartmouth), Lewis is the face of the 21st century unionism, which has been transformed from a movement devoted to protecting the safety and livelihoods of blue-collar workers to a stronghold of white-collar liberalism.

Over the past 30 years, labor has been feminized, professionalized, politicized and regionalized. In the 1970s, Archie Bunker, a loading dock foreman, was a staunch unionist. Today, his son-in-law, grad student Mike Stivic, would be the union member.

According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, the most unionized job category is “education, training and library occupations” at 35.4 percent. That’s a field dominated by women, many with master’s degrees. (In fact, the Center for Economic and Policy Research predicts that by 2020, a majority of union members will be women.) Meanwhile, in manufacturing, the macho vocation that gave birth to the modern labor movement, the unionization rate has plummeted from 30 percent in 1983, around the time the term “Rust Belt” entered the popular consciousness, to 9.4 percent today. Workers in manufacturing are now less likely to be unionized than the workforce as a whole. During those three decades of deindustrialization, the United Auto Workers’ membership dropped from 1.2 million to 390,000. That’s mainly due to robots replacing line workers, and the loss of market share to foreign manufacturers. Because when those foreign manufacturers build plants in the United States, they build in the South, a region hostile to unionism.

Earlier this year, the UAW tried to organize a Volkswagen plant in Chattanooga, Tennessee. Despite the tacit support of the company, which needed an independent union to form a European-style works council, the UAW lost the election, 712-626. Before the vote, the anti-union faction, which called itself Southern Momentum, invoked cultural, regional, racial and political resentments to persuade the conservative white men working in the plant that a union was a threat not only to their livelihoods, but to their way of life. Billboards labeled the Democratic-leaning union the United Obama Workers and presented ruin porn images of the derelict Packard Motors plant alongside the slogan, “Detroit: Brought to you by the UAW.” A pamphlet distributed to workers compared the Northern union’s campaign to a campaign by the Union Army in the Civil War: “One hundred and fifty years ago … the people of Tennessee routed such a force in the Battle of Chickamauga.”

(When I heard a Sheet Metal Workers business agent from Syracuse theorize that Southerners dislike unions because “the name reminds them of the Union Army,” I thought he was nuts. Since Chattanooga, I think he may have been on to something. The man’s own local lost most of its members when the Carrier Corp. moved its air-conditioner manufacturing plants to Georgia and Tennessee — and told union employees they weren’t welcome to follow their jobs. Bottom line: If you buy a BMW built in Alabama, or a Toyota built in Mississippi, you’re not helping the American labor movement.)

Contrast that with the UAW’s campaign to organize graduate employees at New York University — exactly the kind of job Mike Stivic would have held. The union won that vote 620-10. It was a gimme. The UAW was dealing with teachers in the most heavily unionized state in the nation. In New York, 23.2 percent of workers belong to a union. In Tennessee, 4.8 percent do. (Only Arkansas, Georgia, Mississippi, North Carolina, South Carolina are less unionized.)

In post-industrial, politically polarized America, it’s easier to organize Northern academics than Southern factory workers. Union membership used to be a matter of economic self-interest, divorced from political or cultural concerns. In the 1960s, union members — who were disproportionately Roman Catholic — could support the New Deal welfare state, while also backing the Vietnam War, racially restrictive housing covenants and bans on abortion and birth control. Richard Nixon — who used to call his ideal voter “a 47-year-old machinist’s wife outside Dayton” — won his 1972 landslide with a “blue-collar strategy” that attracted the support of white male unionists. Many were voting Republican for the first time, out of disgust for the counterculture represented by Nixon’s opponent, George McGovern. They were personified by Archie Bunker, with his strident admiration for “Richard E. Nixon.”

That election was the beginning of a realignment that found the labor movement on the opposite side of a political divide from the white men who once formed the backbone of its membership. Now, support for labor is just another blue state trait, like support for gun control or Obamacare. In states won by Barack Obama in 2012, 13.1 percent of workers belong to a union. In states won by Mitt Romney: 7.2. Collective bargaining is inimical to the conservative ideal of individualism. Unions are “socialist.” In 1983, over half of union members were white men. Now, a little over a third are. In New York City, site of the famous Hard Hat Riot, in which union construction workers attacked students protesting the Kent State shootings, less than a quarter of union members are white men.

It used to be that belonging to a labor union made you a Democrat. Now, being a Democrat is more likely to make you a union member. Blacks are more likely to be unionized than whites. College-educated whites are more likely to be unionized than non-college whites. Public sector employees are more likely to belong to unions than private sector employees. Teachers and librarians vote overwhelmingly Democratic, not because they’re union members, but because the combination of low pay and intellectual inquiry in those professions attracts liberals. And since most union members now work in the public sector, the war on unions has become a front in the larger conservative war on government. (The one exception: cops and firefighters, who have a 34 percent unionization rate. Wisconsin Gov. Scott Walker left them out of his ban on collective bargaining by public employees, because they tend to be white and conservative. Cops and firefighters can’t strike, though, and are more likely to belong to benevolent associations than full-fledged unions.)

Rahm Emanuel has never been a friend of the labor movement. Bill Clinton’s point man on shepherding the North American Free Trade Agreement through Congress, he was a key figure in the Democrats’ realignment from a party of working people to a party of Wall Street, encouraging the party to responded to labor’s weakness by shifting its donor base from unions to socially liberal financiers. Told as White House chief of staff, that tens of thousands of autoworkers could lose their jobs if General Motors and Chrysler didn’t receive a federal bailout, he responded: “Fuck the UAW.”

Emanuel helped vanquish Old Labor as a force in American politics. Now he’s facing the political fight of his life, against a representative of the New Labor that’s taking its place.