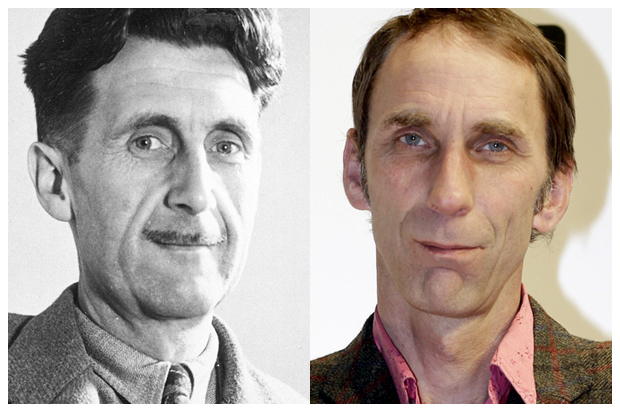

Although he was a writer who strove all his life to express himself clearly, George Orwell has suffered a rash of misreadings of late. The most recent comes from the British novelist Will Self, who in a commentary written for the BBC, accused the author of “1984” of being a “talented mediocrity” whose call for plain speaking in English prose revealed him to be a “small ‘c’ conservative.” Orwell, Self protests, is invoked by present-day “language police” who seek to impose “good old-fashioned prejudices” on a “living, changing” tongue.

This is a wild — and one can only assume willful — misinterpretation of the Orwell essay in question, a famous piece written in 1945, “Politics and the English Language.” The essay, which is always worth revisiting, specifically addresses political writing and attacks such bad habits as “stale or mixed images,” “prefabricated phrases,” “needless repetitions” and “humbug and vagueness generally.” Orwell calls instead for prose that reaches for fresh metaphors and that is precise and concrete. He also argues that getting rid of the “bad habits” of abstraction, pretension and verbal obfuscation will help everyone to “think more clearly, and to think clearly is a necessary first step towards political regeneration.”

The essay also winds up with a list of “rules” designed to guide those “in doubt about the effect of a word or phrase.” This, presumably, is where it ran afoul of Self, because Orwell recommends that a writer “never use a long word where a short one will do” and advises cutting unnecessary words, particularly foreign, scientific or jargon terms, when there is “an everyday English equivalent.” Self has been dunned by critics who complain of his intellectually florid sentences and his penchant for deploying such dust bunnies of the thesaurus as “fulguration” and “lucubration” — two words he included in his BBC piece.

This prose style is Self’s shtick, along with issuing provocations in the newspapers, such as his pronouncement in the Guardian, earlier this year, that the novel is well and truly dead. (Someone has to do this sort of thing now that Martin Amis has moved to Brooklyn.) He is not so much an obscure writer as an exhausting one, and not always able to convince readers that the rewards his work offers will be worth the effort it takes to get them. Still, many Britons are fond of him, for if the English, as Self claims, like their mediocrities, they absolutely adore their eccentrics.

In a dodgy attempt to align himself with the forces of popular vitality and cultural dynamism, Self — truly a Self-styled populist — presents Orwell as someone who wanted to paralyze English in the form used by “a certain kind of clear-thinking, public-school-educated but widely experienced middle-class Englishman.” He lumps Orwell with “authoritarian elitists” who would, he assumes, disdain “African American Vernacular English” in favor of peering “at meaning by the guttering candlelight of a Standard English frozen in time.” This is a ludicrous smear. Orwell’s essay explicitly states that rescuing English from bad writing “has nothing to do with archaism … or with the setting-up of a ‘standard English’ which must never be departed from.” Furthermore, Orwell’s idea of good writing is flexible enough that it “has nothing to do with correct grammar and syntax, which are of no importance so long as one makes one’s meaning clear.”

As flagrantly as he misrepresents Orwell, Self does speak to a real divide among contemporary writers, particularly writers of fiction. There is an approach that seeks to write elegantly and even beautifully but not in a fashion that calls much attention to the writing as writing. These are authors who (to use Orwell’s own metaphor) aim to make their prose a pane of clear glass through which the reader can see the world they describe. The other school, which owes much of its approach to poetry, are makers of stained-glass windows. They place language in the foreground and believe that what an author has to say matters less than how he says it. Of course, many of the most interesting writers use some admixture of these two approaches, but more often than not, one aesthetic predominates.

This is one reason why it’s so difficult to agree on what constitutes “good” writing, particularly when it comes to fiction; the people making such judgments are often applying very different standards. But Orwell wasn’t talking about fiction in “Politics and the English Language,” as he explicitly states: “I have not been considering the literary use of language,” he writes, “but merely language as an instrument for expressing and not for concealing or preventing thought.”

And when it comes to political writing, Orwell’s position remains unassailable. “In our time, political speech and writing are largely the defense of the indefensible,” he writes, a sentence any writer has cause to envy. “Politics and the English Language” is directed not at, say, suppressing the vernacular English of disenfranchised black Americans, as Self preposterously alleges, but at dispersing the fog of “euphemism, question-begging and sheer cloudy vagueness” generated by the powerful and their mouthpieces to obscure the truth.

When Orwell complains of the “decay” and “decadence” of English, this is what he’s talking about, not the natural evolution of everyday speech as Self claims. There is nothing in “Politics and the English Language” that objects to change per se. To the contrary: Change is just what Orwell wanted. “If you simplify your English,” Orwell explains, “you are freed from the worst follies of orthodoxy. You cannot speak any of the necessary dialects, and when you make a stupid remark its stupidity will be obvious, even to yourself.” Will Self might want to try it some time.

Further reading

George Orwell’s “Politics and the English Language”

Will Self for the BBC on “Why George Orwell was a literary mediocrity”

Wills Self proclaims the novel dead in the Guardian