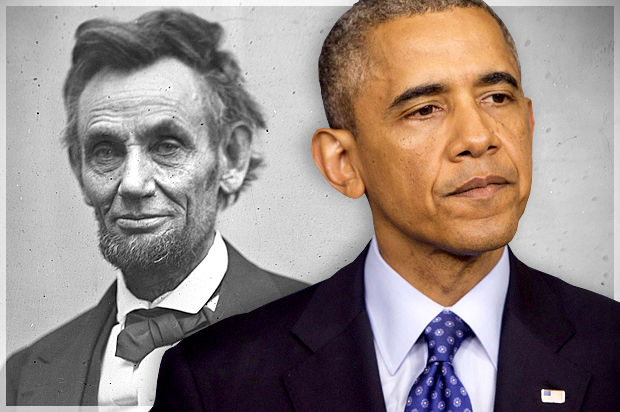

When Barack Obama recited the oath of office to become the 44th president of the United States, he placed his hand on the very same King James Bible upon which Abraham Lincoln had sworn his allegiance to the Constitution. The image was, of course, a powerful one. Here was the nation’s first African-American president connecting with the aura of the president who, nearly 150 years before, had freed the slaves. But Obama clearly intended the symbolism to go beyond this. Lincoln was not only the American president who made his election possible, he was also the president whom Obama most wished to emulate: a man of compassion, who stood for justice, and who occupied a transformative presence on the national stage.

Well, Obama succeeded, just not the way that he hoped he might have. The Lincoln Americans carry in their breast pockets is a mythic figure: a gifted orator – author of some of the nation’s most stirring phrases – who was known as the “Great Emancipator” and who had successfully presided over our nation’s bloodiest war, saving the country from ruin.

All that may be true. But there is another, less affirmative Lincoln that history, so protective of its heroes, has obscured: As president, Abraham Lincoln claimed broad executive powers, was a master of indecision, and, in a nation with deep-seated regional differences, was almost certainly too enamored of the federal solution. In other words, he was a lot like the man in the White House today.

“I’ve got a pen and I’ve got a telegraph”

For someone who was so steeped in the law and the Constitution, Lincoln was surprisingly dismissive of the separation of powers. He claimed that the emergency conditions of the war – which, of course, were considerable – required him to suspend habeas corpus, this despite the fact that the Constitution addresses the authority to do this in Article I, which outlines the powers of Congress, not the executive. Chief Justice Roger Taney noted the breach and called him on it, but Lincoln went ahead anyway.

When he signed the Confiscation Act of 1862 – which Congress had authored to allow the seizure of property, including slaves, from those offering direct support to the Confederate cause – Lincoln, worried that this act might alienate the Border States, penned a draft veto message and, like a modern-day signing statement, sent that to Congress along with his signature enacting the law – “a veto that was not a veto” for an act he signed yet never intended to enforce. And the document for which he is perhaps best known – the Emancipation Proclamation – was, despite its clear moral foundations, a “taking” – that is, a seizure of property without compensation as prohibited by the Constitution. Recognizing that a legislative solution was politically impossible, Lincoln opted instead to “proclaim” the end of slavery in the rebel states – the proclamation serving here as modern-day presidents use the executive order – and to do so under his powers as commander-in-chief.

Equality, the “defining issue of our time”

Lincoln, like so many before and after him, including this president, also had a willful view of the law. Since the Constitution did not yet defend “equality” per se (that would come with the 14th Amendment), he asserted that the Declaration of Independence, a revolutionary manifesto that recognized “all men” as “created equal,” to be superior to the slavery-protective Constitution even though as a manifesto the Declaration carried no legal weight. After arguing that secession itself was unconstitutional – states could not withdraw from the Union simply by declaring themselves dissatisfied, for that, he insisted, was “the essence of anarchy” – he endorsed the 1862 secession of the western counties of Virginia from the rebel government in Richmond when he recognized their application to the Union as a separate state. Even his own attorney general – Edward Bates – had counseled him to reject the West Virginia argument as inconsistent with the sanctity of the Union (“it is a very grave and important thing to cut up and dismember one of the original States of this nation”) but Lincoln acted differently, distinguishing between “secession against the Constitution, and secession in favor of the Constitution” – my secession versus yours.

“The Great Obfuscator”

Perhaps the greatest charge against Lincoln and the one that is certain to provoke the most debate revolves around the ambiguous nature of his rhetoric. No American president had a greater flare for the language than Lincoln, but when he was unsure of his path (which he often was) he used this talent for words to muddle the message. In one of his most famous passages – his open letter of response to the journalist Horace Greeley who had accused him of being “strangely and disastrously remiss” on the issue of emancipation, Lincoln asserted that if he could save the Union “without freeing any slave I would do it, and if I could save it by freeing all slaves I would do it; and if I could save it by freeing some and leaving others alone I would also do that.” The statement was disingenuous at best – he had clear plans to free at least some of the slaves; indeed, the draft of the Proclamation was already in his desk drawer at the War Department telegraph office – and deliberately misleading at worst, for it held out hope to all parties without committing to any.

Then, in a truly revealing moment, Lincoln followed with a gratuitous line of self-declaration: “I have here stated my purpose according to my view of Official duty: and I intend no modification of my oft-expressed personal wish that all men every where could be free.” In other words, if I weren’t president, I would be on the side of the abolitionists. Yet there was such passivity in that word – could – as if he had no authority to do anything.

“God wills this contest …”

As it turns out, Lincoln, despite his exercise of broad executive powers, did indeed feel powerless and his rhetoric may have been less manipulative than sincere: He was often of two minds – even three or four – on any issue he faced and spoke compellingly of each as if he were still working out where he stood. He had been surprised by the turn of events that accompanied his own rise to power: that the Southern states immediately seceded, that the war was not quick and decisive, that not even the Border States, much less the rebellious states of the South, responded to his appeal to institute a gradual, compensated end to slavery. His confusion and disappointment had led to a kind of personal paralysis, one in which he increasingly felt that the power of reason had failed him, making it impossible to act. He had been so certain that he was on the side of right and yet, if so, why did the war and all the suffering continue? “I am almost ready to say that this is probably true –“ he wrote to himself, “that God wills this contest, and wills that it shall not end yet.”

How ironic: The man who asserted such far-reaching authority for himself and his office had discovered a core impotency at the heart of power. The presidency, as so many, including Obama, have found, is a lonely place.