Not too long ago, President Obama was excoriated in the press for what was arguably the single greatest gaffe in human history: “We don’t have a strategy yet.” It was one of those “classic gaffes” in the sense that it supposedly summed up everything wrong with his presidency. It was also one of those “classic gaffes” in that it was taken out of a context that would have rendered it a fairly mundane statement. He was saying that his administration was reviewing military options about how to address ISIS in Syria and would need a little bit more time before settling on the proper plan and taking it to the public. As we wrote, the Worst Gaffe in History was just Obama noting that he needed another week or two to flesh out the deets for a prolonged military campaign. This guy! Taking an extra few days to polish off a strategy instead of just bombing ISIS for a while and seeing what happens? What a clown.

Hopefully everyone had a good time spitting fury over nothing. Because now the hecklers are in the position of getting the prolonged military intervention for which they asked. And even that won’t be enough for some.

The New York Times today fleshes out the details of the ISIS-crushin’ strategy that President Obama first discussed in his “Meet the Press” interview yesterday. Obama will address the country on Wednesday night about the option he’s settled on, one that, according to the Times, “may take three years to complete, requiring a sustained effort that could last until after President Obama has left office.” And simple heuristics suggest that if the administration itself is saying it may take three years to complete, it will most likely end up taking seven to 154 years. Is everyone happy now?

The Times outlines the three phases of the strategy:

The first phase, an air campaign with nearly 145 airstrikes in the past month, is already underway to protect ethnic and religious minorities and American diplomatic, intelligence and military personnel, and their facilities, as well as to begin rolling back ISIS gains in northern and western Iraq.

The next phase, which would begin sometime after Iraq forms a more inclusive government, scheduled this week, is expected to involve an intensified effort to train, advise or equip the Iraqi military, Kurdish fighters and possibly members of Sunni tribes.

The final, toughest and most politically controversial phase of the operation — destroying the terrorist army in its sanctuary inside Syria — might not be completed until the next administration. Indeed, some Pentagon planners envision a military campaign lasting at least 36 months.

Already this sounds quite ambitious, to put it politely, and concerning to those who worry about the U.S. getting bogged down in a multi-year military intervention spread across multiple countries — because that’s specifically what’s being proposed.

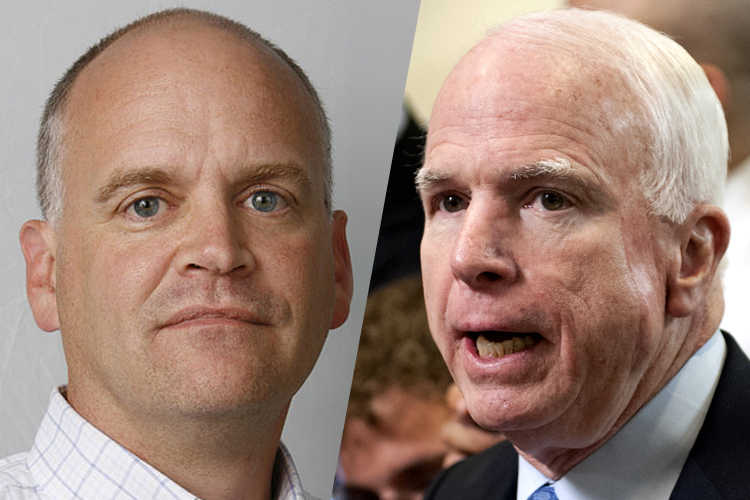

But the critics aren’t satisfied, because Obama has taken the deployment of ground troops off the table. It’s no surprise that this upsets the neoconservative Weekly Standard, who whine incredulously this morning, “A Long War Against ISIS — With No Ground Troops?” Maximalist hawks gonna be maximalist hawks, we suppose, and that means pouting with clenched fists in the corner about how the latest war in the Middle East won’t be war-y enough for their liking.

And then we have National Journal’s Ron Fournier, who somehow Fournierizes the news over a prolonged Middle East military intervention into a concern about President Obama’s lack of leadership and prioritization of politics above all else. Fournier argues that Obama’s pledge not to deploy ground troops offers an advantage to The Enemy, who now have a concrete view of the limit of American resolve and can plan accordingly. It would be wiser for Obama, Fournier writes, to not signal any such limit — to play a bit of the madman strategy and keep the option of ground troops on the table, just to keep ISIS guessing. Since Obama is going against the book on this one, as Fournier sees it, his decision against deploying ground troops must be a political one ahead of midterms. And last but not least, “doves” are the ones who should be most concerned about Obama making a decision based on politics, because a shift in public opinion toward deploying ground troops might lead to the deployment of ground troops.

On the latter point, we’re going to suggest that the public is not going to be in favor of deploying occupying forces to Syria and Iraq any time soon, barring some sort of ISIS-sponsored nuclear attack on America’s cities. Despite Fournier’s clever contortions, people who don’t want ground troops deployed to Syria and Iraq should be happy that President Obama has ruled out deploying ground troops to Syria and Iraq. It’s not that complicated.

As for whether Obama’s decision to take ground troops off the table is “political.” Well, as the administration’s sad decision this weekend to delay executive action on immigration indicated, this president is certainly politically pliable. But if Obama has been consistent on one issue from the time he emerged on the scene in 2004 through the present, it’s that he’s wary of military occupations of foreign countries. Such occupations cost incalculable amounts of blood and treasure, they engender backlash against Americans across the region, and they’re difficult to ever end because the fledgling government comes to rely on the occupying army for security without picking up the slack itself. It doesn’t strike us as some batty political calculation when Obama says he doesn’t want to get into that situation.

What “doves” should be concerned about, instead of Obama’s decision to take ground troops off the table, is the more obvious thing that “doves” should be concerned about: that this proposed intervention is already too much intervention. Even if you’re “just” providing air support, that could also create a dependency situation from which any exit becomes difficult.