When you’ve published a book about Watergate, your phone rings off the hook in the days leading up to Aug. 9, 2014, the 40th anniversary of Richard Nixon’s resignation. But my phone’s been quiet this week — even though the event that took place almost exactly one month later, on Sept. 8, 1974, is the one that really changed the world. It’s still changing the world 40 years later.

Gerald Ford had announced upon acceding to the highest office in the land, “Our Constitution works; our great republic is a government of laws and not men. Here the people rule.” For the sentiment, he reaped a harvest of gratitude. The very existence of this new presidency, everyone said, proved that “the system worked.”

Then, four Sundays later, 11:05 a.m., when many Americans would have, like Ford, just returned from church — in the mood, he hoped, for mercy — Ford proceeded to read, then sign, a proclamation announcing that pursuant to Article II, Section 2 of the Constitution, he was granting “a full, free, and absolute pardon unto Richard Nixon for all offenses against the United States which he, Richard Nixon, committed or may have committed or taken part in during the period from January 20 through August 9, 1974.”

It was an enormously unpopular act. Ford’s approval rating declined from 71 to 49 percent, the most precipitous in history. This pardon was proof, the people said, that the system didn’t work — America was still crooked. Suspicions were widespread that it was the fruit of a dirty deal between Nixon and Ford: the presidency in exchange for the pardon. “The son of a bitch pardoned the son of a bitch,” was how Carl Bernstein broke the news Bob Woodward on the phone.

Since then, judgment on the pardon has reversed 180 degrees. First Woodward, then Bernstein, came to conclude there had been no deal, and that this was instead an extraordinarily noble act: Ford “realized intuitively that the country had to get beyond Nixon.” After Ford died in 2006, Peggy Noonan went even further. She said Ford “threw himself on a grenade to protect the country from shame.”

They’re wrong. For political elites took away a dangerous lesson from the Ford pardon — our true shame: All it takes is the incantation of magic words like “stability” and “confidence” and “consensus” in order to inure yourself from accountability for just about any malfeasance.

In 1975 the Senate and House empaneled committees to investigate the CIA, FBI and, later, the NSA after it was discovered these agencies had operated unethically and illegally. The House committee, under Rep. Otis Pike, who died last year in obscurity, discovered not merely that the CIA was out of control, but that it was incompetent — for instance, predicting Mideast peace the week before the Yom Kippur War broke out. Frank Church’s Senate committee, meanwhile, proved the NSA was illegally gathering the telegraph traffic of American citizens, without even top executives of the telegraph companies being aware of it.

But, in the spirit of the Nixon pardon, the idea of holding elite institutions to reckoning had fallen out of favor. At the height of the intelligence investigations Washington Post’s publisher Katharine Graham complained of the media’s tendency to “see a conspiracy and cover-up in everything.” Sen. J. William Fulbright said “these are not the kind of truths we need most right now,” that the nation demanded “restored stability and confidence” instead. The CIA had no trouble promptly drumming up a disingenuous propaganda campaign that all but neutered reform. And, 39 years later, these institutions are still largely broken, and still almost entirely unaccountable.

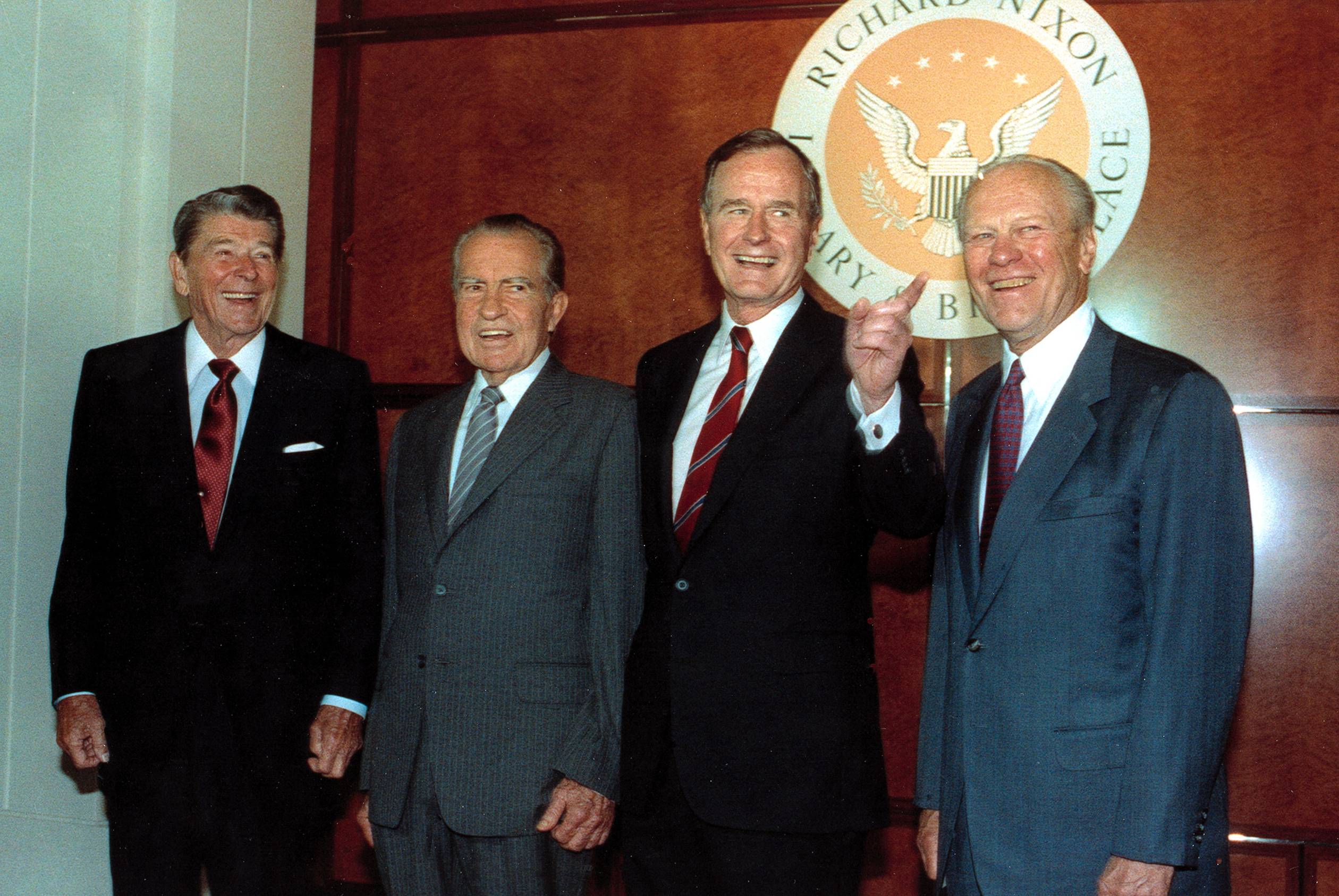

Follow the thread a little more than a decade later. Ronald Reagan’s administration contravened law and its own solemn pledges by selling hundreds of thousands of missiles to Iran in an attempt to free hostages held in Lebanon. The president’s own diaries revealed that he approved the action; he lied about that in a press conference. The deal didn’t even work; Hezbollah just took more hostages. Then profits were diverted to the Nicaraguan Contras in direct violation of congressional statute. But instead of a Watergate-style Senate investigation (the one in 1973 heard witnesses live on TV for over five months and produced 26 volumes of reports), Iran-Contra was investigated by a panel convened by Reagan himself and led by a political ally, Sen. John Tower; at subsequent congressional hearings, deliberately limited in scope, the star witness, Oliver North, testifying under immunity, bragged of destroying thousands of pages of evidence.

Six administration officials, including former Defense Secretary Caspar Weinberger, were indicted by a special prosecutor. But one month before leaving office, President George H.W. Bush — who did not testify in congressional hearings about his own involvement in the affair as vice president, because the Democratic chairman, Sen. Daniel Inouye, wished to spare him embarrassment — pardoned them all.

Just like 40 years ago today, a longing for consensus over messy conflict, for elite comity instead of accountability, “stability and confidence” instead of justice, trumped all.

Meanwhile, the congressional minority report on Iran-Contra, drafted by then-Rep. Richard Cheney, all but rejected the very notion of congressional oversight over the executive branch — and Cheney, as George W. Bush’s vice president, literally took Iran-Contra as the subject for a “lessons learned” workshop on how to put such a foreign policy into practice.

Note, of course, that Cheney had once been top deputy in Gerald Ford’s White House. The Nixon pardon had to have been a lesson learned for him, too — future administrations would let the Bush administration get away with things like illegally spying on Americans, and starting a war on false pretenses, scot-free. And he was right: Following his 2008 election, President Obama announced “that we need to look forward as opposed to looking backward.”

Comity over accountability. Denialism instead of risking national “shame.” In 2001, the John F. Kennedy Library awarded Ford its Profile in Courage award for the pardon decision. But the idea that “too big to fail” institutions are too fragile to handle honest reckoning with the truth is not courage. It is civic cowardice. Better, much better, that we keep the faith: that our Constitution can work, that our great republic is a government of laws and not men, and that here, the people rule.