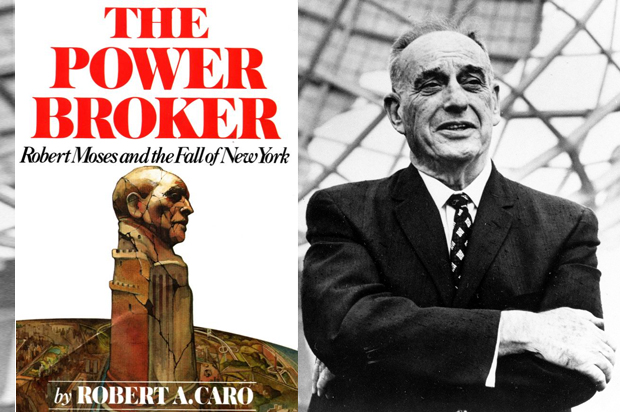

Take an interest in the history of New York City, and someone will soon ask if you’ve read “The Power Broker.”

This is, in part, a good-natured gauge of your interest and experience; the urban affairs buff slyly asking for your credentials. But it’s more often a natural question, since Robert Caro’s biography of mid-century planning czar Robert Moses is so much more than that: It’s a history of urban politics and planning, of bonds, of infrastructure, of bureaucracy and patronage, and, as Caro emphasizes, a study of the use of power.

Though never elected, Robert Moses served nearly half a century in the city and state governments of New York. He built 627 miles of highway in the city and its suburbs. He built enough public housing for 555,000 people. He built hundreds of playgrounds, ballfields and tennis courts in the city, and a handful of enormous state parks beyond its borders. He built the Triborough, Throgs Neck and Whitestone, Marine Parkway, Cross-Bay, Henry Hudson and Verrazano Bridges.

It’s no surprise that most conversations about New York eventually fall into the orbit of Moses — and of Caro’s vast biography. “The Power Broker” isn’t just the best book about this city; it is, according to the historian David Halberstam, the best book about the city.

“The Power Broker” is a classic of great-man history. Yet it’s the stories of the disempowered that resonate most: the potato farmers of Nassau County, the environmental advocates of Inwood Hill, the families of East Tremont, Robert’s own brother Paul. All of them suffered at the hands of the Master Builder, and Caro gives them a voice.

The three chapters on the construction of the Cross-Bronx Expressway, for example, are justly the book’s most famous. Caro so captures the frustration and sadness of the vanished East Tremont community, channels their sense of loss and betrayal at the hands of callous officials, that one forgets he was only 17 years old when the notices of eviction arrived. By the time the author was doing research, East Tremont was an emblematic inner-city ghetto. “I had never, in my sheltered middle-class life, descended so deeply into the realms of despair,” Caro wrote in the New Yorker in 1998.

“The Power Broker” was published at the nadir of New York’s history, give or take a few years. The population fell by more than 10 percent between 1970 and 1980. The year after Caro won the Pulitzer Prize, New York City nearly went bankrupt. (“FORD TO CITY: DROP DEAD,” read the famous headline.) Two years after that, the South Bronx burst into flames during a World Series game at Yankee Stadium. The book’s subtitle summed up its author’s take on the era of urban fear and flight: “Robert Moses and the Fall of New York.”

Was Caro right to link New York’s decline to Moses’ reign? The zeitgeist, from St. Louis to New Haven, was that urban renewal projects had done more harm than good in cities. And New York had seen, thanks to Moses’s tireless draftsmen and shrewd financial practices, more urban renewal than anywhere else. Slum clearance was a known scam; the unbuilt schemes became urban boogeymen, warnings to future generations.

There were some doubts at the time: in a blistering review in the New York Times (a paper that Caro had repeatedly singled out for its sycophancy to Moses), Christopher Lehmann-Haupt challenged the simple conclusion and its implications. “If Robert Moses really is the root cause of our problems that Mr. Caro has made him appear to be … what we need now to straighten us out is another Robert Moses.”

There are certainly doubts about Caro’s thesis now. In the course of New York’s remarkable and well-publicized turnaround, Moses’s reputation has undergone a revision, if not a rehabilitation. As early as 1987, the Municipal Art Society was running a “Robert Moses Reappraised” bus tour, led by “Moses man” Arnold Vollmer. The sociologist Nathan Glazer, in a powerful rebuttal, called Caro’s views “Manichean.”

A handful of influential critics now believe that New York City was able to recover not in spite of Moses’s grand projects but because of them.

Leading the way are Hilary Ballon and Kenneth T. Jackson, historians at Columbia University whose 2007 book is the most thorough document of this thesis. “Had the city not undertaken a massive program of public works between 1924 and 1970, had it not built an arterial highway system, and had it not relocated 200,000 people from old-law tenements to new public housing projects,” they wrote in “Robert Moses and the Modern City: The Transformation of New York,”

New York would not have been able to claim in the 1990s that it was the capital of the twentieth century, the capital of capitalism, and the capital of the world.

“Moses’s surgery, while radical, may just possibly have saved New York,” wrote the architecture critic Paul Goldberger in The New Yorker.

Is Caro’s book is a product of its time? The wrenching scenes of urban renewal in the Bronx, in this view, become indicative of the book’s flaws, its eye on Moses’s victims rather than his achievements. The pivotal Cross-Bronx chapter is called “One Mile,” and its tight focus comes with a powerful implication: that stories like these were buried beneath many of Moses’s 627 miles of urban and suburban highway, and vanished in the dust of the tenements of the Lower East Side and Harlem. But one mile was nothing: the big picture was 627 miles, a feat of construction almost beyond human comprehension.

“In an era when almost any project can be held up for years by public hearings and reviews by community boards, community groups, civic groups, and planning commissions, not to mention the courts, it is hard not to feel a certain nostalgic tug for Moses’s method of building by decree,” Goldberger continued. “It may not have been democratic, or even right. Still, somebody has to look at the big picture and make decisions for the greater good.”

But if Caro was wrong to think New York had died at Moses’ hands, critics are no less short-sighted in thinking he gave it new life. They have fallen into the same trap as the many journalists who lauded Moses in the first place: They are in awe of his power. They are stuck in the contemporary urban political landscape, where subway stations are named for banks and cities must sell condominiums to build parks and libraries. Perhaps it’s natural, in an era when a ban on 64-ounce sodas is what passes for municipal overreach, that we would come to idolize an urban planning superman. Their reflections, like Caro’s original diagnosis, are a product of the times.

Caro’s message, despite its overreach, remains essentially correct: Moses sacrificed New York City’s interests to those of the automobile. New York is back because he stopped short of destroying its assets entirely — plowing three expressways across Manhattan in the interest of regional connectivity, for example.

Moses’s true, toxic legacy is the state of our faltering mass transit system, impressive by American standards but stunted and disjointed in comparison to global capitals like London or Tokyo. The majority of New Yorkers still use this hundred-year-old network to get to work; not coincidentally, we have the longest commute times in the nation.

Caro could imagine, in 1974, what besides expressway construction might have been done with Triborough’s tremendous fundraising capacity. Can we?