After a half-decade in which all things Roberto Bolaño were ravenously consumed, Anglophone readers seem to have finally hit Peak Bolaño. Did the hammer come down in late 2012, when Sam Carter complained of a “Bolaño Bubble” in The New Republic? Maybe it was the July 2013 publication in English of “The Unknown University,” an omnibus of Bolaño’s poetry that weighs in at a whopping 766 pages, in whose pages an eager reader can gorge on the late Chilean’s idiosyncratic verse, charting its transition from avant-garde to nearly essayistic, until their vision fails. Or perhaps the fatigue can be traced to the simple fact that many of the biographical lacunae that made reading and writing about Bolaño so exciting have been filled in, rectified, leaving a man standing in a temple built to an idea.

Whatever the cause, the last year has seen a marked reduction in sweeping, melancholic investigations into Roberto Bolaño’s interior life. For years, the legend of Bolaño—born in Chile, raised in Mexico, imprisoned by Pinochet’s regime, released into a new life in Spain, dead at 50 from liver failure—has been a reliably engaging narrative, drawing in new readers from corners normally unreached by literary fiction. The majority of his English-speaking readers discovered Bolaño after his death in 2003, creating an insatiable hunger for details about his mystery-shrouded personal life. As often happens, this vacuum birthed a plethora of romantic myths: Bolaño as addict, as profligate Latin lover, as pauper, as liar. Substantial articles appeared in nearly every magazine and website with even a passing interest in arts and culture, generating a canon written by fans trying desperately to understand the few certain facts about their favorite writer (full disclosure: I have also contributed to this body of work).

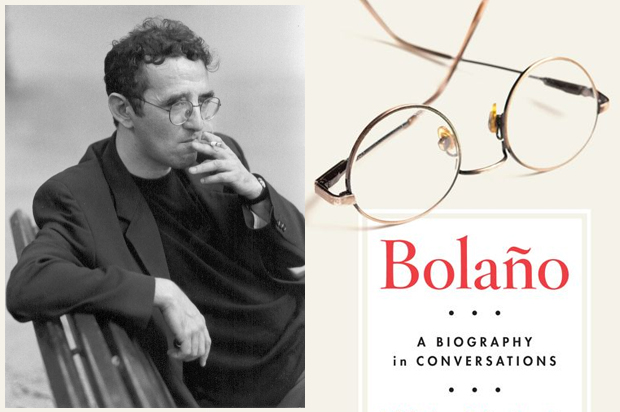

Often, when parsing some supposition-based treatise on Bolaño’s lived experiences, or one of the many articles written about the seeming impossibility of determining who he really was, I have wondered if our hunger for information about the author’s private life is fundamentally American, a reiteration of the gauche hunger for illicit secrets engendered by our tabloid culture. Monica Maristain’s “Bolaño: A Biography in Conversations,” out Sept. 30 from Melville House, exposes the innocence of that assumption; the often-mawkish, possessive curiosity of Bolaño fans, it turns out, is global. Maristain, an Argentine journalist who lives and works in Mexico, has built a career on an interview she did with Bolaño that incidentally turned out to be the final such conversation he completed before his death. This text is now marketed as “The Last Interview,” an unfortunate designation; Maristain’s desperately quirky questions (“Have you seen the most beautiful woman in the world?”) read like rejects from Vanity Fair’s musty Proust Questionnaire and offer little about Bolaño, other than a reiteration of his generally game and genial personality. The interview’s accidental historic import catapulted Maristain into the position of Bolaño expert, earning her a seat on a panel discussion held at the Los Angeles Public Library last year and, presumably, paving the way for “Bolaño: A Biography in Conversations” (first published in Spanish in 2012 as “El Hijo de Mister Playa”).

“Bolaño” is an odd book, not exactly what I would call a biography; driven not by researched fact but the author’s outsized preoccupation with its subject, its closest cousin is film critic David Thomson’s 2006 “Nicole Kidman,” a fever dream at the height of which Thomson shares his fantasy of encountering Kidman in a Paris cathouse, clad in “a very revealing white brassiere, a size or two too small.” Would that Maristain were as deliciously unhinged.

Instead, she writes defensively, constantly attempting to define her authority and justify her book’s existence. In the first pages, she presents a hopelessly skewed and saccharine account of the email correspondence she shared with Bolaño as they arranged the interview, an exchange she elevates to romantic encounter: “He wasn’t shy in our correspondence: Please keep writing, he asked. […] He always ended conversations with an irresistibly sweet phrase.” This brief contact, Maristain explains, inspired her to “make some attempt to bring him back, to let those who knew him best have their say.” Indeed, Melville’s publicity materials for the book promise “rich interviews with the people who knew Bolaño best,” and “new light on aspects of Bolaño’s life [including] the details of Bolaño’s fatal illness and the drama of his final days.”

Here is who is not interviewed in Maristain’s book: Carolina López, the author’s widow, to whom he was married for nearly 30 years, or Lautaro and Alexandra Bolaño, his children (although, in a sleight-of-hand she pulls often, Maristain includes some brief remarks from Lautaro that her endnotes reveal are actually lifted from his brief appearance in a documentary). It’s evident that Bolaño’s most intimate circle did not wish to be involved in the book; quotations from his mother, Victoria Ávalos, and sister, María Salomé, are also sourced from elsewhere. Who, then, does Maristain contend “knew him best”? A cadre of friends, colleagues and admirers, largely from Bolaño’s early days, as well as Bolaño’s father León, from whom he spent a significant portion of his life estranged.

Several of the Spanish literati interviewed in the book’s latter half hint at a falling-out with López that all involved are of course too civilized to describe, but miniature character assassinations on López are offered throughout, with Maristain’s eager prodding. Although the reasons for the divide between López and prominent figures such as Jorge Herralde and Ignacio Echevarría are murky, the book’s obvious slant—and Maristain’s clear partisanship—makes “Bolaño” almost useless as a resource about the author’s life.

“Bolaño” is peppered with randomized, often-contradictory anecdotes about the author’s life, alternating between Maristain’s own reductive summations of the thoughts of others and long, Q&A-format interview excerpts, which seem to be in service to an agenda that never becomes clear. Any new details or personal nuances on offer in “Bolaño” are buried under a leaden and frankly puzzling prose style that I don’t think can be blamed on translation. Maristain seems to have envisioned the book as a kind of cento of disparate remembrances whose meaning would emerge through the act of juxtaposition alone. The technique, if you can call it that, does not work. Sentences proceed from one another willy-nilly, connected tenuously or not at all. In the sections devoted to Bolaño’s early life, Maristain dutifully presents endless images of the author as a young man, making no effort to square them or ascertain their veracity: on one page Bolaño is a hapless agoraphobe, terrified of the world; on the next a charming, precocious conversant; on the third an egotistical spendthrift terror. She never makes up her mind whether he was a lothario or a true romantic. She speculates wildly about what might be revealed when “we” finally have access to Bolaño’s correspondence, and then treats these speculations as fact.

León Bolaño’s presence is intriguing, but the interviews with Bolaño pere only provoke more questions about what, exactly, all of this is supposed to add up to, as highlighted in one unintentionally hilarious example of Maristain’s scatterbrained style:

The old man grows emotional and his eyes well up when he remembers what he felt when he read the story “Last Evenings on Earth” for the first time. The story is about a trip he took with his son to Acapulco in the eighties. “That’s how it was, exactly how he tells it in the book,” León says.

“Last Evenings on Earth” chronicles a road trip from Mexico City to Acapulco taken by Bolaño’s stand-in character B. and his father, a journey riddled with visits to brothels, strange sporting events and gambling, fueled by B.’s slow realization that his father is a self-involved creep and possible rapist. It ends when B. is drawn into a bar fight provoked by his father, in which they are dramatically outmatched. Anyone familiar with the story, one of Bolaño’s most famous, might reasonably assume that this passage will be followed with some poignant detail of the elder Bolaño’s late-in-life realization of his flaws as a father, or at least some paternal recognition of the author’s talent. Instead, we get Maristain’s immediate, unasked-for sentimental forgiveness:

Much has been said about the estrangement between father and son that led to a silence between them that lasted for almost two decades. However, there is evidence to show that the bond between Roberto and León was much closer than the hasty obituary written in the heat—or cold—of the death of the writer tended to allow.

The above passage encapsulates the book’s most infuriating quality: Maristain’s habit of presenting the reader with prepackaged opinions and then bumbling onward, never providing the “evidence” she promises. Her own florid feelings about Bolaño are never far from view, and her value judgments about her interview subjects are awkwardly obvious. Carmen Perez de Vega, a woman who Maristain contends was Bolaño’s “partner” and “companion” in the last years of his life, is always flatly described as “beautiful”; she is “a woman of undeniable beauty,” and “a fascinating woman of remarkable intelligence and sensitivity” (the last two descriptions appear on the same page); Carolina López, on the other hand, is “obsessively discreet.” Gee, I wonder why—guess which one of them granted Maristain access and an interview.

Elsewhere, Bolaño’s publisher, who fell out with López after his death, casts aspersions on the authenticity of the author’s posthumously published work, saying “It’s a little strange […] it’s beginning to be a little like Pessoa’s trunk, a bottomless trunk… I don’t know.” It’s difficult to parse Maristain’s game; why present statements like this one straight, without criticism or investigation? With the deck so stacked against the Bolaño intimates who did not wish to be a part of her project, “Bolaño” begins to seem like something more sinister: a revenge project. Before launching with glee into a bleak account of the author’s last days, the private details of which serve no obvious purpose other than to satisfy ghoulish curiosity, Maristain writes of the controversy surrounding López and Perez de Vega: “The entire story has become somewhat tedious and has nothing to do with appreciating Bolaño’s work, which is essentially all that matters.” The author surely did not intend to describe her own book with this phrase, but the shoe fits.

If you are interested in understanding more about the work of Roberto Bolaño, you may be interested in the elegantly written literary analysis “Roberto Bolaño’s Fiction: An Expanding Universe” by his first English translator Chris Andrews, which was published earlier this year by Columbia University Press. Or you can go back to the first and best source, the one that established the craze in the first place: Bolaño’s fiction. “Bolaño” itself—what a shame that Maristain claimed that definitive title!—offers at best a handful of suspect stories and idiosyncratic insights from people who, like all of us, held strong opinions about the man himself.