We need to talk some more about affirmative consent. Not just because New York governor Andrew Cuomo ordered the state’s universities to overhaul its sexual assault investigation guidelines in favor of a “yes means yes” standard last week — which he did, and which is a big deal, and which we will talk about — but also because a great many people might be confused about why two of the nation’s largest states, New York and California, are moving toward affirmative consent policies on college campuses.

I imagine people might be confused about this trend because, just this morning, I read a piece from a prominent national media outlet (New York Magazine) by one of its well-known writers (Jonathan Chait) with a headline (“California’s Radical College-Sex-Law Experiment”) that seemed to feed into a lot of the rape apologia-hysteria surrounding affirmative consent laws. So let’s clear some things up.

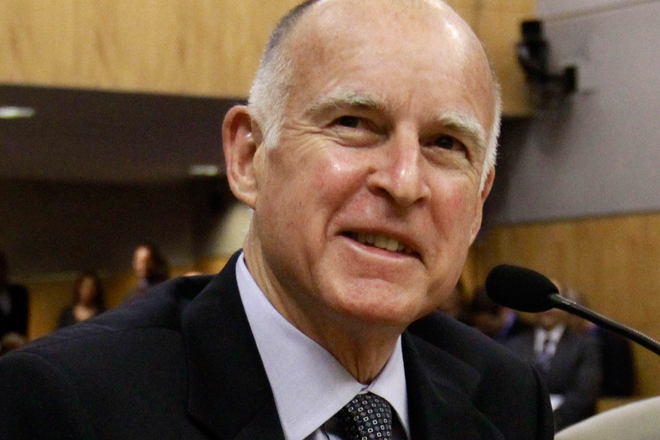

Chait’s piece refers specifically to California’s recent affirmative consent mandate, which Gov. Jerry Brown signed into law last week. The law requires all California colleges and universities that receive state funding to define sexual consent as an enthusiastic affirmation of a desire to have intercourse, and clarifies ambiguities in the “no means no” conceptualization of rape. Specifically, the law states that “lack of protest or resistance does not mean consent, nor does silence mean consent. Affirmative consent must be ongoing throughout a sexual activity and can be revoked at any time.”

Critics have decried the law as an overreach into students’ sex lives and an overly broad expansion of the definition of sexual assault, which they say could potentially have countless innocent men declared rapists. The latter concern seems to worry Chait, too, who asserts that “most, and possibly nearly all, sexual encounters will legally be rape” under the new law, and that “accusation will almost automatically result in conviction” in campus sexual assault investigations. He writes:

Indeed, this may be the point. Culp-Ressler dismisses concerns about convictions of innocent people. (“In reality, false rape allegations are very rare, comprising about two to eight percent of all reports.”) Two to 8 percent seems like a fairly high number of innocent people to convict as rapists, and of course that proportion could well rise quite a bit under a legal regime that expands the definition of rape in ways that are both extremely broad and extremely confusing.

Obviously, failing to convict a guilty rapist is bad, too. There is no downside-free resolution that would avoid unfairness one way or another.

It’s true that there is no downside-free resolution when it comes to addressing sexual assault, but that has nothing to do with unfairness to the men accused of sexual assault; innocent men are not routinely convicted as rapists, and they will not routinely be convicted as rapists under affirmative consent laws. First, Culp-Ressler’s point holds: False rape allegations are rare and, on top of that, punishment isn’t so easily doled out. A recent Huffington Post investigation found unconscionable statistics on the rates of expulsion for campus rapists, finding that fewer than a third were forced off campus after being found responsible for sexual assault. Second, as has been crudely illustrated by reports of sexual assault in the Alt Lit community, a lot of rapists don’t see themselves as rapists. Period. Society doesn’t see them as rapists, either. And that’s exactly why — as even Chait concedes — there is a desperate need to reconfigure how we think about sexual assault. Men are not innocent of rape simply because they “misunderstood the signals” or weren’t totally sure about consent; they are rapists who do not understand that they are rapists.

There is no downside-free resolution to dealing with sexual assault, because when we do deal with sexual assault — you know, if that even happens — it generally means a sexual assault has occurred. That’s a tragedy, and right now it’s a tragedy that occurs too many times a year on college campuses across the country, affecting too many victims who find themselves with virtually no recourse — victims whose chances at justice are trampled by their abusers walking freely around campus. And obviously that is a problem, because failing to convict guilty rapists is bad, bad, bad, according to Chait.

But failing to convict a guilty rapist is not just bad. It is routine. It is the standard. And that is exactly what the California law, and what the new SUNY policy ordered by Cuomo last week, aims to make less likely. Beyond that, affirmative consent standards have the power to catalyze a change in our conceptions of rape and consent — a change that Chait himself says is necessary:

Deprogramming and reorienting societal ideas about sex is an evolutionary process. California isn’t merely attempting to set out to nudge the culture in this direction. […]

If most college students today do not think that sex without continuous, affirmative consent is actually rape, and there is a law in place rendering it as such, soon enough, somebody is going to be prosecuted under these terms.

Yes, soon enough somebody will be prosecuted under these terms, and it will likely be because he or she had sex without consent and because someone reported it as sexual assault. This is what should happen. But here is what should also happen, and very likely could: There will be other somebodies out there who, keeping in mind the new law and their desire not to be prosecuted for rape, decide to ask their partners for clear consent. Instead of pushing ahead when a young woman says she “isn’t sure” she wants to have sex, there will be a young man who pursues a direct, enthusiastic “yes” before moving forward. There will be college students thinking twice about their actions, talking about sex and then, one hopes, having it consensually.

This is not radical. It is optimistic. The only thing that is radical about codifying “yes means yes” standards into law is that we are actually doing something to combat sexual assault. Finally, prominent media outlets might begin to recognize the need to call rape “rape,” or begin to question people who want to curb efforts to stop it. Finally, there might be a measure that can result in the cultural change education has failed to make, for which we cannot wait any longer. Finally — and this is the most radical idea yet — we might be able to afford survivors justice.