A few weeks back, Yahoo!’s Michael Isikoff broke a story that inspired feelings of bitter vindication among U.S. foreign policy critics, but went mostly unnoticed by the population at large. In a statement to Isikoff, the White House acknowledged for the first time that the civilian-protecting restrictions on drone strikes President Obama announced to great fanfare last year were not being applied to its new anti-ISIS campaign in Iraq and Syria. Translated from the purposefully anodyne language of a statement to the press, the White House’s message to civilians near ISIS targets was simple and clear: You’re on your own.

To critics of U.S. policy in the greater Middle East, Yahoo!’s report was an unwelcome confirmation of a nagging suspicion and fear. Namely, that Obama’s 2013 drone speech — during which the president outlined a long list of reforms his administration would implement to the drone program — was little more than presidential lip service, and that the U.S. was still running its counterterrorism like a game of Calvinball, the imaginary sport from “Calvin and Hobbes” whose only real law is that player/creator Calvin gets to do whatever he wants, whenever he wants to do it.

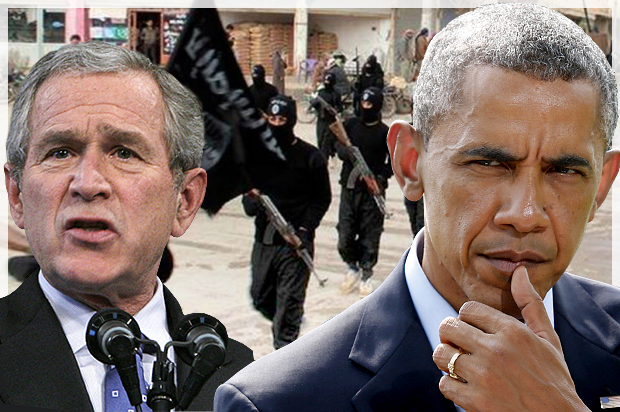

It’s no longer a surprise, of course, to find Obama upholding Bush’s legacy on national security policies. What’s troubling, though — and what the new war on ISIS has made even more clear — is that despite being nearly six years through the Obama era, our famously cautious, rational and legalistic president has done little to clean up and clarify the legal and political counterterrorism framework left to him by his predecessor. The war on terror is bigger and more entrenched than ever, and it’s still being waged according to secret rules.

For experts in the field of human rights, the Yahoo! report was both disappointing and unsurprising, with some seeing it as just the latest manifestation of a dynamic that’s been present throughout Obama’s years in the White House. In conversations with Salon, members of Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch shared concerns over the White House’s statement to Yahoo!, but emphasized that they were unable to weigh in more authoritatively due to the administration’s insistence on keeping secret much of the law supporting targeted killings and other uses of force against terrorist organizations.

“The fact that we’re even having this conversation stems from the decision by the administration to not be clear about what law governs,” said Human Rights Watch Deputy Washington Director Andrea Prasow after noting Obama’s 2013 drone speech “was clearly policy, not law” and therefore non-binding. “The Obama administration has used targeted killing in circumstances that may not be an armed conflict,” Prasow said, “and in those cases, human rights law is the law that governs. If the [ISIS] decision was to apply … to those situations,” she continued, “the policy is illegal.”

If all that sounds quite hypothetical, it’s because it is. “We don’t know if particular strikes are part of the armed conflict which Iraq requested the U.S. join, or if they’re strikes against al Qaeda as part of the administration’s claim that it’s in an armed conflict with al Qaeda and its ‘associated forces’ around the world,” Prasow said. “It’s difficult to know how to analyze [drone strikes] and how to figure out which law governs. We don’t know what’s actually happening.” The president’s 2013 address was supposed to answer many of these questions and provide greater. It hasn’t.

Amnesty International Senior Policy Adviser Avner Gidron’s read on the situation is much the same. “We’re a bit skeptical about these really rigorous standards that they [supposedly] apply to drone attacks in the first place,” Gidron said. And because the administration never followed-through on its 2013 promises, Gidron noted,” it’s impossible for us to even assess” whether their actions against ISIS are a clear deviation from what they were doing before. “Because of the complete lack of transparency,” Gidron said, “it’s impossible … to assess whether this policy about drone strikes is actually being applied to those situations where they said it would apply.”

A belief that the promises made in 2013 have not been fulfilled is not a sentiment exclusive to human rights activists and attorneys, either. “There were a series of announced policy revisions after an extensive inter-agency review in May 2013,” Council on Foreign Relations’ expert Micah Zenko told Salon, “but most of those were never implemented. If you go through the list of things they said they were going to do,” he continued, “they just never did them.” And the items of the list weren’t minor or secondary: “Transferring [the drone program] from CIA to DOD, uniform standards for all [strikes], transparency, capture over kill … the repeal of AUMF … everything they said they were going to do they didn’t do.”

Yet while Zenko agrees that the 2013 speech has seemingly been all but ignored, he doesn’t think it’s right to describe it as lawless. The administration was “worried that they could have externally imposed constraints on how to conduct drone strikes, just like the Bush admin did with warrantless wiretapping, torture and rendition,” Zenko said. “So they wanted to avoid that and they knew they needed to become more transparent.” Yet for all the promises of openness and restraint, Zenko said, the gap between what the administration says its policies are and what it actually does remains significant. “That gap is by definition hypocrisy,” Zenko said. By refusing to provide real clarity, Zenko said, the administration “allowed people to project the worst myths and misperceptions into the strikes — that’s certainly what happens in places like Pakistan.”

Adding a whole new layer of confusion is the fact that the strikes against ISIS, despite being undertaken in part with drones and being described by the administration as in-line with strikes against targets in Yemen and Somalia, are in truth much akin to old-fashioned warfare, with its indiscriminate destruction and slaughter, than the administration seems inclined to admit. For the human beings in Iraq and Syria who are at risk of becoming “collateral damage,” that’s a distinction without a difference. But for those trying to follow U.S. military actions and, if necessary, hold Washington to account, the vague overlap between the U.S.’s many conflicts — the difference between a strike that falls under the AUMF and one justified by the Iraqi government’s request for help — makes all the legal difference in the world.

Yet despite all this, the deflating reality, one well familiar to Obama supporters, is that as disappointing as the president’s record may be, it’s still the case that in terms of placing targeted killing and the war on terror on solid legal footing, his predecessor’s legacy is even worse. “The Bush administration conducted 50 non-battlefield targeted killings and never said a word about them,” Zenko reminded. “And when the UN special rapporteurs asked [about the strikes], they refused to give an answer.” The current administration, on the other hand, “made an attempt to put some phrases and terms around what they were doing.” In the bizarro world of the U.S. war on terror, broken promises and “phrases and terms” represent a real change.