For almost a decade, I rejected the idea of moving to Brooklyn. First, because Brooklyn seemed too far from the center of things and, I thought, offered primarily the sort of amenity that you might as well go to the suburbs for: more space for less money. If I was going to move to New York, I wanted to, you know, live in New York. Later I resisted it for a different reason. Brooklyn, far from seeming like the outskirts of town, had become too trendy. I liked to think of myself as independent-minded. I disdained “hipsters” (and was more intimidated than I wanted to admit by women who seemed impossibly cool, in a vintage clothes–wearing, bespectacled way that I admired without being able to emulate).

And so I spent ten years doing New York all wrong, ten years in which I was very often lonely and constantly on the verge of leaving.

Sure, there was an early period of infatuation when I first moved to the East Village in my early twenties. It was the late 1990s, and I felt a great sense of romance about the city and especially the neighborhood. I was happy to have found a cramped fifth-floor walk-up on East Eleventh Street—and proud I hadn’t been persuaded by real estate agents to take one of those spacious one-bedrooms in some distant Brooklyn neighborhood called Park Slope. I did love Alphabet City back then—the used bookstores, the dive bars, the dog run at Tompkins Square Park. I especially loved the cafés and coffee shops—the grungy ones you could still smoke in, full of bike messengers reading Nietzsche or grad school dropouts turned bartenders, i.e., people wholly different from the types I knew from college, whose concerns revolved around grades and GPAs and law school. It didn’t matter that I barely knew anyone in the city. The streets themselves felt like a party, the kind of party I most wanted to be invited to, full of passionate, interesting nonconformists.

Although I didn’t know enough to appreciate this quality back then—I recognized it only years later, long after it was gone—I was open to new experiences in a way I think is characteristic of youth, a way that is both admirable for its adventurousness but also a bit tainted by the narcissistic desire to live life as if it were for a story you were telling someone later. Back then, if I was bored, I might sit at a coffee shop and read and people-watch, and end up in a long conversation about the neighborhood’s history with a silver-haired man whose grandchildren were around my age. I might walk to Washington Square Park to play chess for a few bucks a game. I had long conversations with strangers—and not merely potential dates, in my “demographic.” I remember a set designer in his early fifties and clearly gay. He approached me when he saw I was reading George Eliot in Tompkins Square Park. I never saw him again, and yet I’ve never forgotten him. He said his favorite Eliot novel was Romola, an unusual choice. Years later, when I used a line from Romola as my novel’s epigraph, I thought of him. I also became friendly with the guys who worked at the parking lot next door to my apartment building and who hung out on the sidewalk when there were no cars to park. When I baked, I brought them brownies and cookies. After I dropped a bottle of wine so that it shattered outside my building’s front door—I was coming home with supplies for a dinner party—one of my parking lot friends gave me a present of a box of wine, which, he noted drily, I was unlikely to break.

I loved New York that first year. I wasn’t lonely. But something happened. Nothing and everything. The banalities of adult life overtook the city’s romance. I left the East Village for Queens to move in with a boyfriend. It didn’t work out. I moved back to Manhattan, to a worse apartment than the one I’d left. I went from waitressing to a professional job, working as a reporter for a financial trade publication. The company was called Institutional Investor. I got a subscription to the Wall Street Journal and often worked late. I didn’t bake as much, and I didn’t spend time chatting with guys who hung out on the sidewalk. I became very concerned with paying back the credit card debt I’d racked up in that first irresponsible year and a half of waitressing and frequent relocations. I entered into a new relationship, which, unlike the one that had taken me to Queens, would last for a number of years and which felt very grown-up in ways that were both good and bad. By my midtwenties, New York no longer felt like a constant party. It was just the place where I lived. As time went on, that meant it would be the backdrop for a lot of unhappiness.

*

One of the biggest sources of unhappiness was my dissatisfaction as a writer. I worked as a financial reporter, but I wanted to be a novelist. However, I had yet to write a word of decent fiction, which caused me some anxiety but did nothing to improve the quality of my writing. When I was twenty-six, I went to journalism school, believing that journalism was a good day job for an aspiring novelist and that journalism school would lead to a more interesting reporting job than the one at Institutional Investor or the one I’d had after that, at a small newspaper in Connecticut. I thought—correctly—that grad school would help me to get a job at a better newspaper. I went to Columbia, which brought me to Morningside Heights, a neighborhood that didn’t have the same romance for me as the East Village. It was also far from most of my friends, who increasingly lived in Brooklyn. But I had a good deal on a rent-stabilized apartment.

After journalism school, I got an internship at the Plain Dealer, a newspaper in Cleveland, and because it was just an internship, I held on to the rent-stabilized apartment, subletting it to two friends from school. When my internship was extended, my subletters stayed on. When, after about eight months, the Plain Dealer offered me a full-time job, I didn’t know what to do. By then the long-term boyfriend and I had broken up, our pseudo grown-up relationship having devolved into a rather strained and joyless version of adult life. Even though my life in Manhattan hadn’t thrilled me in years, being newly single in Cleveland wasn’t great either. In the end, I declined the job. I decided to return to New York to make a go at being a freelance writer. After all, I had an affordable apartment waiting for me. How many people could say that?

Things didn’t go quite as I hoped. Freelancing was harder than I expected, both financially and, more surprisingly, emotionally. I considered myself an independent, readerly type of person. I liked solitude, or so I believed. Then I discovered that being alone for the whole workday made feel a little sad and a little crazy—a realization that poked a little hole in my proud self-conception. My previous jobs, from Institutional Investor through the Plain Dealer, had provided with me more, psychologically, than I had realized, had been more than paychecks and experience for the résumé. At home by myself, I became the kind of person who constantly emailed friends about nothing. “How is your morning?” I’d write to Alexis at eleven a.m. “What did you do last night?” I’d write half an hour later, forgetting that Alexis didn’t need to spend her day shooting the shit with me. She had real live coworkers to do that with.

I began dating a reporter for a New York paper and felt an acute power imbalance unlike anything I’d have anticipated. My boyfriend’s days were spent with coworkers or in packs of photographers and reporters from competing papers as they waited for hours at a time outside a subject’s home or office. At the end of the day, he simply wasn’t as hungry for companionship as I was. Plus he was often drawn into spontaneous happy-hour drinks after work, the way I had once been—back when I had coworkers. Because of his job, he was regularly invited to all sorts of fancy parties. It didn’t matter that most of the parties weren’t especially appealing—they were PR events for new products or companies—it was the principle. No one invited me to their PR events, not now that I was just a freelancer.

Most important, I didn’t much like the work I was doing. I mostly wrote business stories for newspapers and trade publications, but I hoped to do more arts and culture writing and to break into magazines. For the first year or so that I worked freelance, I imagined happiness was just one promising assignment away—all I needed was for some magazine editor to give me a shot—but I found myself losing heart as time went on and no one did (somehow I had thought good things would just happen if I lived in New York and was freelance— i.e., threw myself in fate’s path). Besides, I was so focused on trying to get enough work to pay the rent that I didn’t have that much energy left to strategize about orchestrating my big break. Soon I lost any belief that I was moving forward, toward something better.

Why, you might be wondering, if I was so unhappy, didn’t I pack it up and get a regular job? All I can say is I think something happens to people who’ve freelanced for a while. At least it happened to me. Even if you begin by choice, after a time you start to feel unemployable— somehow inferior, marked out for a strange and marginal existence, distinct from that of those well-socialized full-timers whose company-sponsored email addresses and holiday parties are, like engagement rings, proofs that they are loved—or at least claimed. That’s how I felt, anyway. I assume it’s different for people who freelance at a higher level than I did, who win National Magazine Awards and get flown across the world to conduct interviews with world leaders.

By my late twenties, I was—I won’t say unhappy in my career, because “career” seems too lofty and grandiose a term for what I was doing then: writing tedious columns about personal finance for low pay and no benefits. Let’s just say I was unhappy professionally. My personal life was also a bust. The newspaper reporter and I had long since gone our separate ways, and I wondered how likely I was to meet anyone new when my work life was conducted from home and consisted mostly of telephone calls to middle-aged financial advisers who lived with their families in the suburbs. Plus, I lived so far from most of my friends—an hour subway’s ride to Brooklyn—that I saw them relatively rarely, when we made plans to meet up for a meal in downtown Manhattan, often at some too-loud restaurant.

The unhappier I got, the more isolated I became. I had less and less desire to get together with a certain type of casual friend, the kind for whom you feel compelled to put on at least a moderately good face, to present your life in terms that are not entirely depressing. Some friends energize and others enervate, a good friend of mine (an energizer) once noted—and when you feel the way I did, a much higher percentage enervate.

My unhappiness made me ashamed. I had become a lonely, professionally stalled single woman in a city that is said to be full of such women, and a culture that is often contemptuous of us, that makes jokes about cat ladies, that both pities and blames us. (I’m not sure which is worse.) That my unhappiness was so commonplace, so clichéd made it all the worse. I had once, with the arrogance of youth, thought I’d never be that kind of woman; I was too ambitious, too passionate in my intellectual interests, too willing to work hard to ever become someone who would be categorized this way, whether or not I was romantically attached. My belief that I was different from other women was the kind of personal exceptionalism that ought to get shucked off as one grows older, and yet the process of ridding oneself of comforting illusions is, of course, painful.

The most important thing I did—perhaps the only important thing—during those years was read. I read not just obsessively but in a disciplined, programmatic way, going through the entire body of one author after another. Since my early twenties, I’d been drawn to eighteenth- and nineteenth-century writers. This taste for older books was invaluable for me as a writer, but it had drawbacks for me as a social human being. I wasn’t getting excited about new fiction and going to readings where it’s possible I might have met actual flesh-andblood people whom I could become friends with. I worked alone, and at night I read alone, often with a bottle of red wine in lieu of company. I assumed—rather myopically, it turns out—that this was pretty much what everybody did. I thought New York was a sad city, a place full of trapped, isolated people hungering for connection.

*

I was so desperate that, at twenty-nine, I returned to my old bedroom in my parents’ house in suburban Baltimore. It was just going to be for six months; my plan was to write a novel in that time and then return to New York. Now or never, I told myself. I quit the personal finance column and sublet my apartment. Still, no one was more surprised than I was when I actually pulled it off. I produced a 550- page document that could only be called a novel, with a large cast of characters and a plot consisting of a beginning, a middle, and an end.

I returned to New York with the taste of triumph in my mouth. I thought I’d send the novel to literary agents and soon have a publishing deal. I wasn’t eager to return to my lackluster freelance lifestyle, so instead I found work as an SAT tutor. I figured I’d only be doing it for a few months, until my book sold and I was too busy being interviewed by the likes of Terry Gross. I was an SAT tutor for seven years.

The year I turned thirty felt like a very long one. Over the course of many months, I came to realize that no one wanted to publish that novel. Rejection is always hard. This one seemed like not only a reflection on my writing; in practical terms, it felt like my last hope had been extinguished.

But one important piece of luck had befallen me that year. An old friend from high school had come to New York to do a postdoc at Columbia. He moved into my spare room. If he hadn’t been there that year—cheering me up, distracting me with talk of his life and his problems, or initiating long conversations about life and art and politics—I’m not really sure how I would have gotten through. What a different place New York was when you interacted regularly with other humans. When Matt moved out in the spring, I decided to give up the Morningside Heights apartment, no matter how good a deal I had. I didn’t want to be lonely again. I had to make a change. I wanted to be around people I related to; I had to move to Brooklyn. The desire to see myself as different—as not the kind of writer who would live in Brooklyn like all the others—was a luxury I could no longer afford.

*

Objectively, moving to Brooklyn seemed like a fairly desperate move. After all, they say that moving doesn’t change anything because you bring yourself—and by extension your problems—with you. Well, I am here to tell you that this is not always the case.

What I had previously thought of as life in New York—cold, solitary, gray—turned out to have been merely my life in New York. When I moved nearer to the few friends I was still fairly close to, I met their other friends, the ones they saw all the time because they bumped into each other in the neighborhood and grabbed impromptu cups of coffee. I didn’t know that people in New York sometimes called each other up and suggested meeting up that very afternoon or evening, in an hour or two. I had assumed that kind of casual socializing had gone the way of 1950s-style double dates to the movies and soda shop. It turns out that not living an hour’s train ride from your friends helps. (Who knew?) I became closer to my old friends, whom I not only saw more of but saw in ways that were more meaningful—not just at restaurants but for walks in the park or at our apartments for home-cooked meals and drinks and late-night talks. I also, seemingly effortlessly, made new friends.

None of this solved my overarching life problems—it didn’t make my unpublished novel get published or make SAT tutoring any more satisfying—but it made me a great deal happier, happier than I had thought possible after the years of slowly accruing loneliness. It’s easy to mock Brooklyn for its superabundance of writers and publishing types, the stupefying number of people walking around carrying tote bags from one or another independent bookstore or book publisher. But I have come to believe that there are far worse things than a place full of people who like to read.

About a year after I moved to Brooklyn, a guy I’d begun dating (a friend of a friend) encouraged me to begin another novel. He thought the time had come for me to quit moaning about the one that didn’t get published: it was time to move forward. He was right. The experience of writing that first novel had taught me two very important things: that I could write a novel—which was more than I knew for most of my twenties—and that I really liked doing it.

I began a new novel. Perhaps because I had felt isolated for so long, I took a rather anthropological interest in Brooklyn’s literary scene and used it as the setting for this novel, dissecting it through the eyes of my protagonist, a far more successful—and less lonely—freelancer than I’d been.

This novel took me four years to write. I wasn’t buoyed by giddy exuberance the way I had been when I wrote my first one. I knew that writing a novel doesn’t mean that it will be published. I was also, as the years went on, increasingly anxious about being a thirty-something tutor. When strangers asked me what I did for a living, I didn’t know how to respond. Could I really say I was a writer? According to my tax returns, I was not a working writer but a tutor with a Microsoft Word document.

But I was also among friends, to a degree I hadn’t been since college, and this made a tremendous difference. With my friends, many of whom were also writers, I didn’t feel like a failed novelist/journalist or an overaged tutor. My friends took my novel seriously. As I wrote, I gave it to several of them chapter by chapter. Some of my fondest memories of those years are sitting in the spare, book-lined living room of my friend Melissa’s apartment, with her roommate, discussing my latest chapter—or Melissa’s roommate’s latest—over too much wine as we occasionally huddled by an open window to smoke a cigarette (technically I’d quit years ago, but I made exceptions). The other person who read the novel chapter by chapter was my boyfriend, the one who encouraged me to begin. (He’s now my husband.) Other friends read it in chunks. Their comments were helpful, but what was even more helpful was being among people who treated novel writing as my “real” job, never mind that I had no agent or publisher or guarantee of success, that I’d never published a word of fiction.

This may sound minor, but it wasn’t, at least not to me. To be taken seriously as a fiction writer helped me through the difficult stretches. It offset some of the discouragement that I, like most unpublished fiction writers, got plenty of. Many people in my life knew what had happened with my first novel and were concerned about my future, worried I was wasting valuable time on a childish dream. They figured, not unreasonably, that if I’d been any good, the first novel would have been published. This was not unkind; they wanted to protect me from more disappointment.

What I appreciated most about my writer friends was not that they built me up with grand hopes but that they knew how publishing worked and knew me and were cautiously optimistic. One can feel beaten down by pessimists who tell you that “nobody” unknown or unconnected ever gets published, but the well-meaning certainty of affectionate but naïve friends—those lovely, loving people who assure you that as soon as you finish your novel, it’ll be picked by Oprah, since after all you’ve been a great writer “since kindergarten!”—can also be problematic. Measured optimism, grounded in knowledge, is a real comfort.

Almost five years to the day after I moved to Brooklyn, The Love Affairs of Nathaniel P. was published. Some people read the book as a satire of Brooklyn, but to me the mockery comes from a place of deep fondness. The world of the novel, a world full of aspiring writers, is, I think, troublesome in terms of certain gender dynamics; it is also permeated with a grating status consciousness. But I don’t think sexism or status consciousness are unique to Brooklyn—and I think the Brooklyn of the novel, like the real Brooklyn, offers other compensations, in terms of community.

Of course, I don’t think that every writer needs to live in Brooklyn, or New York, or needs writer friends. It’s personal. And an aspiring novelist who does want a community of writers can surely find it in other ways—an MFA program comes to mind. (I didn’t take that path because, rightly or wrongly, I believed my literary tastes and particular novelistic ambitions were out of step with MFA values.) All I can say is that for me, community turned out to be more important than I realized when I was young—important to a degree that is humbling—and I happened to find it in Brooklyn.

The New York that is dear to me, the one that took me ten years to find—because I am slow and stubborn and prone to missteps—has nothing to do with celebrity or wealth or five-star restaurants or, for that matter, organic vegetables or artisanal anything. New York for me is a group of people who, in my early thirties, meant the world to me, a group of not-quite-struggling-but-not-quite-arrived writers who supported each other over endless cups of coffee and glasses of wine, who listened to one another’s romantic travails and learned about each other’s families and read and believed in one another’s work.

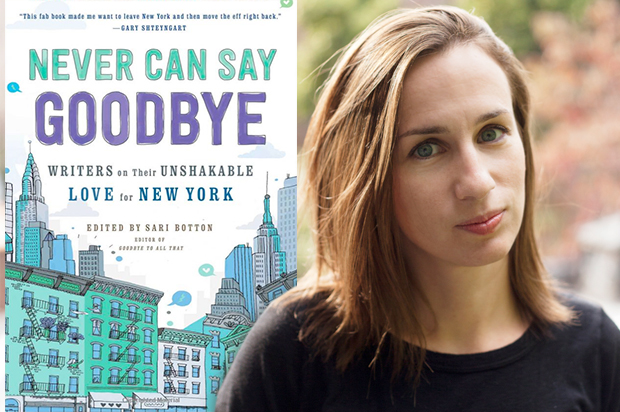

Excerpted from “Never Can Say Goodbye: Writers on Their Unshakable Love for New York” edited by Sari Botton, published by Touchstone, a Division of Simon & Schuster, Inc. Copyright © 2014 by Sari Botton. Reprinted with permission.