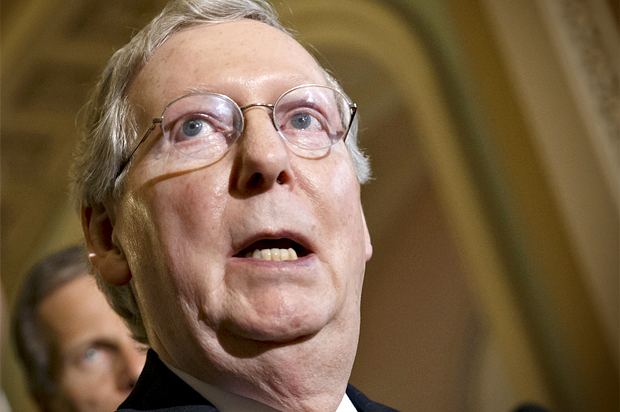

When New Republic editor and Mitch McConnell biographer Alec MacGillis was asked recently by Salon to name a single overriding belief or cause that has maintained the Kentuckian and possible soon-to-be Senate majority leader throughout his career, the best answer MacGillis could come up with wasn’t about taxes or healthcare or abortion. It was opposition to campaign finance reform, something the hyper-competitive but talent-deficient Republican has always hated and seen as a roadblock on his path to power.

And that’s why it’s all too perfect to see McConnell fighting for his life this year, during a campaign in which the public’s interest in campaign finance reform — as evidenced by the Senate campaign in South Dakota and the gubernatorial election in New York — is greater than it’s been in years. Recently, Salon called David Donnelly, the CEO of Every Voice, a nonpartisan nonprofit focused on comprehensive campaign finance reform, to talk about his organization’s midterm goals and the future of money in American politics. Our conversation is below and has been edited for clarity and length.

Tell me about Every Voice. Who are you guys, and what are you trying to do?

Sure. Every Voice is a national organization that tries to reduce the influence of money in politics. We work at the state and federal level to [promote] far-reaching campaign finance reform that lifts the voices of everyday Americans in our political system.

We also know that in order to win we have to build political power and we engage in political activity to elect champions [of reform] and defeat opponents [of reform] so that legislative chambers at the state and federal level are representative of the people’s views on the issue of money in politics.

So what was your strategy for the 2014 cycle, going in?

We were looking at a number of state-level opportunities. We’re focused on two right now; we’re doing work in several New York Senate districts and we’re about to do some work in Maine. Those [efforts] are all very much devoted to advancing campaign finance reform in those two states.

In addition, we want to support champions and defeat opponents on the federal level. We helped to elect seven members of Congress in 2012 through … a super PAC that we set up in 2012. Those candidates are running for reelection …

And we’re also engaged in two Senate races, which are probably the most exciting [of our campaigns]. One features our biggest opponent in the country, Sen. Mitch McConnell; and we’re also trying to elect Rick Weiland in South Dakota. We got in that race early, and we did a significant amount of advertising against one of his opponents. Others have now joined that fight and it’s going to be a barnburner until Election Day.

As you alluded to just now, the race in South Dakota is suddenly quite competitive — and people who support campaign finance, in particular, are being told that they should pay attention to this race. What was it that made you want to get involved early? And why is a Weiland victory so important?

Rick Weiland is a true champion on the issue of money in politics, and when we looked around the country for where we could make a significant difference in the Senate races, this race stood out.

In part, that was because of Rick’s agenda and policies; but it was also because we saw a pathway to influence this race while many others did not. So we began engaging in this race … right after Labor Day. We’ve been up now with about $750,000 of advertising that we purchased for this race; we’ve moved the [poll] numbers significantly; and we’ve attracted an additional amount of spending in this race, on both sides, because it’s gotten much closer.

This is an incredible opportunity to show that a [campaign finance reform] champion can be reelected, after having closed a significant gap. So we’re proud of the support we’ve already shown for Rick Weiland in this race, and [helping to] make it close; but I think we’ll be even more thrilled if at the end of the day he’s a U.S. senator.

To your point about showing a campaign finance reformer like Weiland can win a major race — how much of what you’re doing right now is geared toward proving to political insiders and the like that the conventional wisdom is wrong and that campaign finance reform is something that people care enough about to vote on?

A lot of the people who subscribe to conventional wisdom say [campaign finance reform] doesn’t really matter.

We can win ballot questions, we can see progress through legislatures and win in state legislatures, we can win elections on the basis of where candidates stand on this issue; and still the people within the system will point to some nebulous idea [of] conventional wisdom that says [campaign finance reform] doesn’t matter. But we have so many different measurements [showing] that the issue matters a tremendous amount to voters.

I’m less concerned about debunking conventional wisdom than piercing the cynicism that voters have around this issue. With the courts being so far out of whack with what Americans want, with Congress being so set in its ways, it’s easy to get hopeless [about campaign finance reform]. So what I’m really interested in is … presenting a more positive vision of where it is we want to go, and we need to show success stories getting there.

We need to point out where candidates are participating in good public financing systems; we need to point out where counties are passing new [campaign finance] laws; we need to point out where candidates have lost on the issue of money in politics, so we can show there’s a strategic pathway forward.

We need to pierce the cynicism and turn toward telling stories about solutions rather than just [talking about] the problem, because if we continue to hammer away at the problem of money in politics [and say] it’s so hard, there’s an avalanche of special interest money — who wants to fight against an avalanche? That is a story of deepening cynicism; we need to show there’s a pathway toward moving policy.

Why do you feel that focusing on multiple races, some of which are local and thus unlikely to get a ton of attention, is a better strategy than going all-in for one high-profile supporter of campaign reform like, say, Zephyr Teachout?

It’s a question of strategy. New York is a really good example. There, a major obstacle is the state Senate. Our decision in New York [was] to engage in electoral campaigns with partners to elect more pro-reform senators. If successful, we will then go to work to pass Fair Elections through both chambers and place it on Governor Cuomo’s desk. That will be a historic day.

It should go without saying, but I’ll say it anyway: We’re deeply inspired by Zephyr Teachout’s campaign, and her leadership and scholarship on the issue of money in politics, and are proud that she’s recently rejoined our board of directors.

Some reform proponents have argued that opponents of big political spending shouldn’t try to fight fire with fire and raise gobs of money of their own. How do you and the other people at Every Voice explain your approach?

We’ve long thought that it’s important to demonstrate some political consequences for being on the wrong side of the issue of money in politics. … We’ve done a significant amount of work during the last decade and a half to shape the outcome of elections.

Throughout that period of time, we’ve long said that we embrace the irony of spending money to influence the outcome of elections in order to change the policies that regulate how money flows in and around politics. We’d be very ecstatic about working ourselves out of a job at some point. We don’t want to do this forever; we’re only in it to pass comprehensive policy to reduce the influence of money in politics.

But if we have to use the existing tools to change the rules of the game, [campaign finance reform] is too important … to set down those tools and stay on the sidelines and hope for something better. We’re very clear-eyed and pragmatic about making a significant difference in the way elections are financed, and in order to do that, we need to use politics.

Now, in terms of the “how” when it comes to campaign finance reform, do you agree with those who’ve said the movement has been too focused on restricting the flow of money into the process? Should there be a greater focus on including more regular people — through public financing or democracy vouchers — and less concern with keeping the hyper-wealthy’s money out?

I think reformers spend too much time focused on … how to get money out of politics. Because while we want to reduce the influence of money in politics, the real question, in my mind, is how do we bring the people back in? And that is a more participatory frame than just trying to stop all the money.

We know from years and years of experience that just pushing all the money out the front door just means it’s going to flow in from somewhere else or screw up some other part of the system. So while we need strong regulations in our campaign finance system, we also need to incentivize more participation and more involvement from everyday people — and that means [promoting] systems that rely on lots and lots of small donations, rather than just a few.

The answer to the problem of money in politics isn’t just getting the money out. It’s about bringing people back in, and you have to reconcile that with the policies that would actually do that … and there are several different ways to do it, but the goal has to be amplifying the voices of regular people in our system.