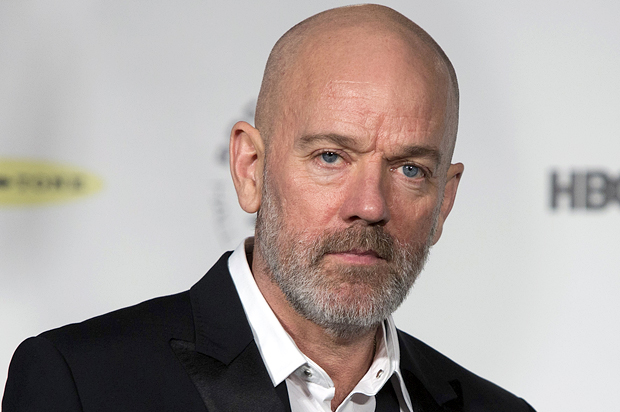

Erstwhile R.E.M. frontman Michael Stipe celebrated the 20th anniversary of his coming out on Sunday by penning a brief and eloquent essay for the Guardian reflecting on changing perceptions of sexuality over the past few decades. The singer, while promoting 1994’s “Monster,” first confirmed his identity as “a completely out, publicly queer individual.”

The anniversary is news to some. Confusion still abounds over when Stipe actually came out, because he had to do it again and again to get people to listen — in 2001 for “Reveal” and again in 2008 for “Accelerate,” at least — a symptom perhaps of how many people, as he writes, wanted their idea of him to remain stuck in time, no matter how often he challenged it.

“It was a simple fact, and I was happy to announce it,” Stipe writes, while acknowledging that not many of his peers had stepped forward at that time. What was groundbreaking in 1994, the year of the Clinton administration’s “don’t ask, don’t tell” military policy, is now routine. But the fact that he had to come out in the press multiple times (eventually mentioning a boyfriend, a concrete detail reporters and readers could process) underscores how uncomfortable people could be with real-life manifestations of the ambiguity they so prized in his work, clinging instead to their personal projections of Stipe as a guesstimate wrapped in a mumble, a pocket indie-rock turducken of lyrical riddles who could be whatever they wanted him to be. His own truth, as he states it: He has enjoyed sex with men and with women. He’s mostly tried to avoid binary labels of gay or straight, offering the expansive “queer” instead.

Stipe celebrates how the conversation has progressed and deepened around sexuality away from those rigid distinctions. Indeed, snide cut-downs still heard in the early-’90s like “bi now, gay later” and “L.U.G.” seem to have disappeared from the discourse, and we’re all better off for it. The conversation continues to shift to a more inclusive continuum of sex and gender, identity, attraction and expression. There’s still a long way to go and it’s been a slow change, but looking back to 1994, a dramatic one.

Stipe offers an optimistic vision of the 21st century, of a universally accessible queerness as:

“a state of mind brought about by an understanding: it is understanding difference, accepting your own truth, desire and identity, and lovely, lovely choice. It is the final, completely obvious contemporary acceptance and understanding that this enormous world of beauty, sexuality, identity, lust, feeling, excitement, and love isn’t just black and white, or simple, at all – it is literally every shade and gradation of the rainbow.”

Underneath the celebratory diction is a bit of a radical statement: that it’s time for an understanding of and acceptance of the breadth and depth of human experience to replace easily digested labels, to move toward a culture that doesn’t get so hung up on whether anyone’s gay or straight, because everyone falls somewhere in between those opposite poles. And he even closes with a challenge, that this vision includes “accepting and supporting positions that you may not even completely understand.” If Stipe’s process of publicly coming out as queer — repeatedly, until everyone listening finally got the message — can teach us one thing, it’s to stop wasting energy on trying to decode every single facet of complex humanity for our own comfort or the comfort of others. The next step: civil rights laws to protect all, so that all may declare their own convictions and lovely, lovely individual truths to all who will listen and be free to develop the clarity of voice that has served Stipe so well.