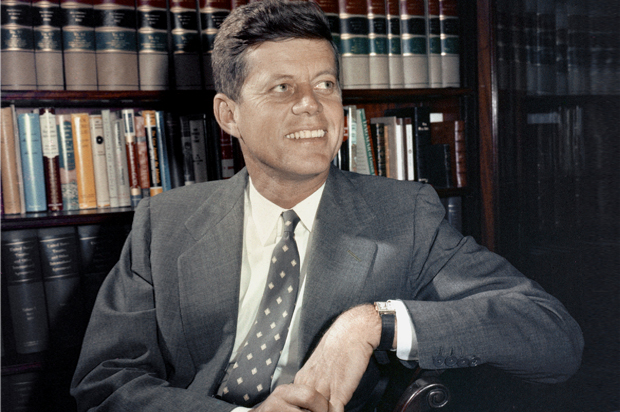

Before Jacqueline Bouvier came along, Pulitzer Prize-winning biographer Margaret Coit dated John F. Kennedy, a young senator who would become the 35th president of the United States a few years later. This historian’s little-known oral history at the JFK Library provides a first-hand acount of what it was like to date the enigma known as Jack Kennedy. This is an excerpt from “When Lions Roar: The Churchills and the Kennedys,” by Thomas Maier.

In the early 1950s, Congressman Jack Kennedy rented an apartment in Georgetown, living the life of an eligible bachelor whom many women found appealing.

“He was the golden boy . . . every girl in Massachusetts wanted to date him, and I wasn’t any exception,” recalled Margaret Coit, winner of the 1951 Pulitzer Prize for her biography of John C. Calhoun. As a potential girlfriend of the future president, however, Coit would see another side of Jack’s personality, different from the all-American image of his political ads.

In the spring of 1953, Coit came to Washington to research a new book about millionaire financier Bernard Baruch, and feigned a reason to interview the thirty-five-year-old Massachusetts senator. “I thought up what possible excuse I would have to meet him because he was not a friend of Baruch’s although his father had been,” recalled Coit, who’d read Jack’s book

Why England Slept,” about the lead-up to World War II. Previously she’d tried asking Jack’s father, Joseph Kennedy, about Baruch, but the former ambassador to Great Britain was appalled by her sleuthing. “He frightened me to death, kind of barking at me, roaring at me,” Coit recalled.

Instead, she spoke with the younger Kennedy in the senator’s outer office, where they discussed his recollections of England before World War II. “I took down my notes, but all the while he was looking me over,” she recalled.

When they finished, Kennedy invited her to a party a few days later at his Georgetown town house, where he barely paid any attention to her, lost in conversation with another senator. At night’s end, Jack put his arm around Coit and said aloud to his sisters at the party, “Isn’t she the prettiest thing you ever did see?” Margaret, though only two years younger, blushed with embarrassment. His sisters sighed, perhaps for Coit’s benefit, and wished Jack “would meet some nice girl.”

Coit didn’t hear from Kennedy for a few more days, not until he asked her again to his office. He quizzed her about Baruch and offered “something very penetrating about Clare Boothe Luce’s private life and a little malicious.” Then Jack sat next to Coit on an office love seat, put his head back, and nearly passed out. “It was as if all the energy had drained out of him,” she recalled. “I thought he was going to faint, and I was so scared I didn’t know what to do.”

As he recovered, they agreed Jack was too tired to go out on a date that night and instead would drive her home. Kennedy stood up gingerly, the result of his wartime back injuries. He reached for his crutches, leaning against the wall. Together Coit and Kennedy walked through the empty corridors of the Senate Office Building and got into Jack’s open convertible with its faded blue paint and fair share of dents. They drove wildly through the Washington streets until they reached the rooming house where Coit was staying. She invited him in, thinking he might want to rest for a moment.

Inside, Jack collapsed on the living room sofa, and then tried to drag Coit down beside him. “Don’t be so grabby,” she said, moving away. “This is only our first date. We have plenty of time.”

Kennedy lifted his head and, for a moment, stared at her with his penetrating gray eyes.

“But I can’t wait, you see, I’m going to grab everything I want,” Kennedy insisted. “You see, I haven’t any time.”

Coit didn’t understand this driven, very complicated young politician and the aggressive way he apparently treated women. “We had been talking about books and ideas and my concepts of the books on Baruch, and then he had seen me as one kind of person,” she recalled. “He had seen me as a mind; and now he saw me just as something female. He couldn’t fit the two together, and it was as if he were two parts. He was like a 14-year-old high school football player on the make; and he was like an elder statesman of sixty in his intellectual process—the two together and it was the cold machine-like quality that scared me so.”

Eventually, the young couple jumped back into Kennedy’s convertible for another spin. This time, while driving along, Jack’s mind returned to the world of books.

“My brother Bobby told me you had won the Pulitzer Prize,” he said, with the wind rushing by, blowing through their hair. “You never told me that. You are very modest. I would rather win a Pulitzer Prize than be president of the United States.”

They drove around some more until Jack’s mind turned to another subject.

“Tell me something else,” he said, with steering wheel in hand. “How did Bernard Baruch make his money?”

Still feeling feisty, Coit remembered Joe Kennedy’s silence and tried to enlist his son in her literary cause. “Pretty much the way your own father made his, I would imagine,” she replied drolly. “Why don’t you ask him?”

Jack staked his own claim. “I want to make millions,” he vowed. “I am going to outdo my father.” When they drove past the White House, Jack appeared quite serious as he looked through the gates. “I am going to go there,” he stated with determination.

Kennedy seemed surprised that Baruch had convinced Coit to write her next biography about him. “What I am interested in is me,” he kidded. “Why don’t you write a book about me?”

“You are not important enough yet,” Coit replied.

Jack smiled, undaunted. “Well, you could put me in a book—’Men I Have Known,’” he teased.

After a while, Jack dropped her off again at the rooming house and assured her, “I’ll call you.” Coit felt relieved. She had dated aggressive men but no one as erratic as Jack Kennedy. “It was the coldness that frightened me and the fact that he was out of a much more sophisticated background than anything that I knew,” she recalled. “I just wanted out of there.” She did take Kennedy’s advice, however, and read Churchill’s magnificent biography of Marlborough, Winston’s glorious ancestor.

The day following her date with Jack, as part of her research for the Baruch book, Coit talked with Arthur Krock, the New York Times columnist who often flacked as Joe Kennedy’s ghostwriter and political adviser and as a secret literary agent for his son. Krock had won a 1951 Pulitzer for his commentary, the same year as Coit did for her book. She mentioned to Krock that she’d met the young senator.

“John Kennedy—what a tragedy that boy is,” Krock announced, mostly solemnly.

Surprised by his reaction, Coit asked the Times man to explain himself.

“Don’t you know he is going to die?” he asked, incredulous at her ignorance.

Coit didn’t believe him. “What are you talking about?” she demanded.

Krock remained quite resolute. “His father told me that he had only four years to live,” he replied.

Suddenly, Jack’s rash and seemingly inexplicable statements about impending doom and eternity made sense to her. “That explained a lot to me, particularly those things—‘I am going to grab everything I want. You see, I haven’t any time,’” she reflected decades later.

Not long after his encounter with Coit, Jack became engaged to Jacqueline Bouvier, a beautiful “Inquiring Photographer” for the Washington Times-Herald whom he had met several months earlier at a dinner party set up by friends. Bouvier shared his love of books, and her Catholic heritage made her an acceptable choice to both Jack’s parents and his Boston Irish constituency. Their fashionable wedding and reception—at the Newport, Rhode Island, home of Jacqueline’s mother and stepfather, Janet and Hugh Auchincloss—was touted in the media by the Kennedy publicity machine. The couple eventually moved to a rented house on Dent Place, in Georgetown, not far from Bobby and his wife, Ethel.

After his first year of marriage, Jack’s deteriorating back required major surgery in New York, a 1954 operation dangerous enough so that he was once again given last rites by a priest. “I can’t go on like this,” he told his new wife. Jackie Kennedy slowly grasped how much her husband’s infirmities defined his existence. “I always thought of him as this enormously glamorous figure whom I married when he was thirty-six,” she recalled. “I thought he’d had millions of gay trips to Europe, girls, dances, everything. And of course, he had done that, but I suppose what he meant was that he had been in pain so much.”

During the long recuperative period, Jack tried to get his mind off his troubles by trying painting, and by reading aloud from Winston Churchill’s “A History of the English-Speaking Peoples.” Eventually, lying in his bed surrounded by books and research, Jack launched a Churchill-like book project published in 1956 as “Profiles in Courage,” which quickly led to literary fame. The book won the Pulitzer for biography in 1957, after Joe Kennedy pushed his friend Arthur Krock to lobby the board on his son’s behalf.

As his father once advised, writing a book kept his son in very good stead. “Profiles in Courage” would help set the stage for JFK’s presidential bid in 1960, a reminder that his Harvard-trained intellect made him something more than another Irish Paddy off the street. Even Margaret Coit was impressed, congratulating the senator on his prize.

“Thanks for thinking of me—but don’t count on a repeat performance!” Kennedy wrote to his fellow Pulitzer winner on official Senate stationery. Scribbled next to his signature, Jack added a personal aside: “When are we going to meet again?”

Excerpted from “When Lions Roar: The Churchills and the Kennedys” by Thomas Maier. Published by Crown, a division of Penguin Random House. Copyright © 2014 by Thomas Maier. Reprinted with permission of the publisher. All rights reserved.