I thought of Oscar Wilde when I read about the recent arrest of Mike (the Situation) Sorrentino. Can’t see the connection? Let me explain.

I wasn’t shocked to learn Sorrentino was taken into custody. He had displayed far too many examples of poor impulse control on ”Jersey Shore.” What was surprising was the crime he was accused of committing: hiding nearly $9 million from the IRS. Apparently it pays to be famous merely for being famous. Very well, in fact.

That someone like Sorrentino had become famous at all is a reminder of how dramatically the definition of “celebrity” has changed. A word that once referred exclusively to persons of achievement – artists, athletes, politicians and so on, who left their mark on history through their deeds – has expanded its meaning to include those who are well known only for being well known, a status won by preening before the media. No other real-world accomplishments required. In this vocational path fame isn’t the end product of a career. It’s the beginning of one.

This value system – one in which everyone thinks they could be famous and, even more to the point, should be – is usually ascribed to cultural institutions that emerged beginning in the late 20th century: the rise of cable television and so-called reality TV; the impact of the Internet and the self-invented YouTube star; and the emergence of a less widely used, but undeniably more sensational, new “medium” – the sex tape.

But the credit for this new worldview actually belongs to an individual born 160 years ago this month in Dublin. Oscar Wilde called it into existence after arriving in America in January 1882 to embark upon a yearlong lecture tour, during which he crossed our nation from New York to California and back again, making nearly 150 personal appearances as he traveled – usually by rail but, when absolutely necessary, by mule – roughly 15,000 miles. Calling himself a professor of aesthetics, though he had studied classics at Oxford, Wilde lectured on interior decorating before audiences ranging from 25 to 2,500 while wearing satin breeches, silk stockings, silver-buckled pumps and a form-fitting velvet jacket with lace trim. In between engagements he granted nearly 100 interviews – more than anyone else in the world in 1882. Some American reporters mocked him as an “ass-thete” or “she,” but those rude hacks underestimated their target. Beneath Wilde’s delicate persona – the rouge-wearing dandy languidly flinging his hand to his brow as he sang the praises of sconces and embroidered pillows – was a steely individual on a mission: to make himself a star, no matter how little he had done (so far) to deserve it.

And make no mistake: He had done very little. When Wilde landed in New York he was not the legendary Irish writer we know today. He was 27; it would be years, in some cases more than a decade, before he would write "The Importance of Being Earnest," "An Ideal Husband" or "The Picture of Dorian Gray." At this point in his life he had written only a self-published book of poems that sold a few hundred copies and a play – not a comedy, but a turgid drama about revolutionaries in Czarist Russia – that closed while still in rehearsals.

But he had made a name for himself in London as a party guest. He was foppish (arriving at one soiree with a live snake around his neck); he was amusing, issuing a litany of dinner-table epigrams, such as “True friends stab you in the front”; and he was opinionated, especially about art. Which is how he ended up in America. Wilde was hired to go there by Richard D’Oyly Carte, the business manager of Gilbert & Sullivan, to promote "Patience," the newest Gilbert & Sullivan operetta that had just opened in New York. Patience was a satire of the British aesthetic movement, a movement united behind the slogan “art for art’s sake.” (“The most beautiful things in the world are the most useless: peacocks and lilies, for instance,” John Ruskin had written.) To W.S. Gilbert, however, the movement was a nirvana for useless narcissists and an excuse for self-adoring dandies to natter away in public about their exquisite taste. One of those dandies was the recent Oxford graduate Oscar Wilde; it was said the character Bunthorne in "Patience" was modeled on him.

Carte was worried "Patience" might not be as popular in America as "The Pirates of Penzance" because the aesthete was not a native species there. Could Wilde be induced to travel to the States to act as a living “prop,” giving lectures on art and interior decorating while shilling for Gilbert & Sullivan? Carte offered half the box-office receipts from the talks, less expenses.

Wilde accepted. He had his own business plan, however. He would spend some of his time promoting "Patience." But he would spend all of it promoting Oscar Wilde. And he succeeded, leaving twelve months later as the second-most-famous living Briton in America, behind only Queen Victoria.

He was able to do that because he devised a strategy and a set of rules for fame creation that aspiring celebrities are following today, whether they realize it or not. One of his rules was “Work the Room.” Wilde, who never forgot that the product he was putting on display was himself, attended nearly 200 parties in America, writing to a friend in London: “I stand [in] the reception rooms when I go out, and for two hours they defile past for introduction. I bow graciously and sometimes honour them with a royal observation.” “Royal” observations such as this, said to a woman who asked for advice on arranging decorative screens in her Fifth Avenue apartment: “Why arrange them at all? Why not just let them occur?”

Another rule was “The Subject Is Always You.” No matter what question was posed to him by American journalists – and these queries ranged from “what is art?” to asking his opinions on hog butchering and the boxer John L. Sullivan – Wilde understood that the answer should be autobiographical. That he grasped this, despite the fact that he had never been interviewed before (not in London, Oxford or anywhere else), is impressive evidence of Wilde’s intuitive P.R. savvy.

He also understood that “Celebrity Is Contagious,” which is why he made a concerted effort to meet – and, even more important, be seen meeting – famous people wherever he lectured. Wilde breakfasted with Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, drank homemade wine with Walt Whitman, and dined with Louisa May Alcott, Henry Ward Beecher, Oliver Wendell Holmes, Henry James and (one wonders how many people could say this in 1882) Ulysses S. Grant and Jefferson Davis, though not, in this final instance, at the same time. Long before the advent of the “V.I.P. Room,” Wilde grasped that celebrity – or, in his case, proximity to celebrities – enables one to join an elevated elite. And that the whole point of joining that elite is to be observed there. From below.

Perhaps the most lasting of his strategies, however, was “Strike a Pose.” Days after his arrival, Wilde posed himself as an aesthetic Adonis for the New York photographer Napoleon Sarony, the most sought-after portraitist in the United States in 1882. He then used those photos as his “logo” as he crossed America. By the time Wilde left the country, his face was one of the most recognized visages in the United States – so much so, that it was used in advertisements to sell consumer products ranging from men’s hats to women’s bust enhancers. That we are still looking at those portraits – and that they still define Wilde’s brand today, 132 years later – shows how foresighted Wilde was in understanding the commercial and promotional powers of photography.

After returning to England, Wilde told Robert Sherrard, eventually to become his first biographer, that the conclusion of his American lecture tour signified the end of “the Oscar of the first period.” His goal in that period had been to reverse the usual process of gaining stature as a literary man: to achieve fame first, and then, in the second period, to use that celebrity to build a career as a writer. The first period of Oscar had ended in resounding success. And though he didn’t know it yet, so too would the second. "The Picture of Dorian Gray" was published to great acclaim in 1890. His first stage comedy, "Lady Windermere’s Fan," was a smash in London’s West End in 1892, as was "A Woman of No Importance" in 1893, "An Ideal Husband" in 1895, and, only a few weeks later, his masterpiece, "The Importance of Being Earnest."

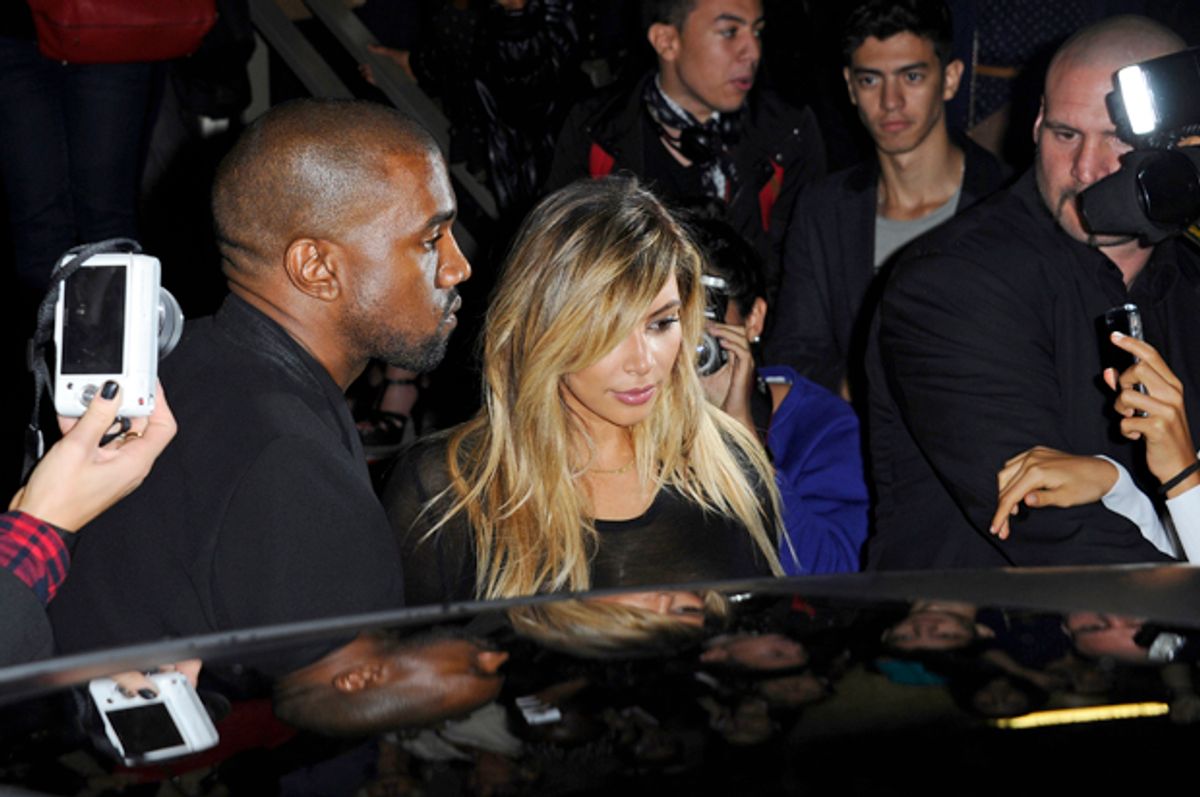

Wilde’s novel is still in print and his peerlessly witty plays are still produced, a testament to his enormous talents as a writer and an achievement for which he is rightly recognized. But he made another enduring, if more controversial, contribution to our civilization, one he hasn’t been fully credited for – one that enabled Mike (the Situation) Sorrentino to become not only famous, but rich. Decades before Norman Mailer, Wilde knew the value of “Advertisements for Myself.” Decades before Andy Warhol, Wilde saw the beauty in commerce and the importance of image in marketing. Decades before Kim Kardashian, he grasped that fame could be fabricated in the media. Decades before TMZ or Us Weekly, Oscar Wilde created celebrity culture.

Shares