As the usually dull State of the Union, the always stage-managed party conventions and the quadrennially horrific Iowa caucus can all attest, politics in the new world can be just as fastened to outdated ceremony as that in the old. Still, as much as I may roll my eyes every year when I see the most powerful person in the world obligated to “pardon” a turkey, I think one of our newest, less-noticed traditions may be our worst one yet. In case you haven’t guessed, I’m referring to the flood of “dark money” — unregulated political spending from sources which are intentionally difficult to trace — that gushes across the country during the final moments of every campaign.

Yes, now is the time for one of the nastier traditions of post-Citizens United America, those few weeks during the fall of every-other-year when Americans can see (through a FOIA request, darkly) what it looks like to buy an election.

Even if they wouldn’t describe the phenomenon in those terms, anyone who’s been watching television or listening to the radio during the past few weeks knows it already; this is when the number of campaign ads goes from “numerous” to “ubiquitous,” after all. But for those less interested in advertisement anecdote than data, the New York Times has a Monday report offering more empirical confirmation. Due to the sudden springing to life of dozens of previously nonexistent or dormant super PACs, the Times has found, the average amount of money spent per-day last week by outside groups was $20 million. No less than $200 million was spent in October alone.

At this point, a reasonable if perhaps naive person might wonder why all this money is raining down so late in the game, with just weeks and sometimes only days to spare. Wouldn’t political funders want to make an upfront investment in hopes of establishing control over the terms of the debate? And isn’t it a truism of our era that the length of every campaign season is getting longer and longer? In both cases, the answer is yes. But this is where the naivety comes in; because it’s not like these donors haven’t taken all of this into consideration. They have. They’ve just determined that the benefits outweigh the costs when it comes to holding their financial fire until the very end.

Those benefits are chiefly related to disclosure, of course — in the sense of having a better chance of being able to avoid it. Asked to explain the almost instantaneous proliferation of blandly named and big spending super PACs during the campaign’s final weeks, Kathy Kiely, managing editor for the pro-transparency Sunlight Foundation, told the Times it was just one more way for political donors “to hide money from the public.” Because the elections will already be over by the time experts and journalists are able to figure out from whence its spending came, Kiely said, “it looks like people are deliberately trying to mask the source of the money.” Reading the Times’ descriptions of just some of these late-stage ads, I can understand why.

One automated phone call in North Carolina, for example, reportedly warns listeners that the state’s consummately middle-of-the-road Democratic senator, Kay Hagan, is an “extreme liberal.” Another one, this time in Louisiana, warned voters unfortunate enough to pick up their phone that the state’s conservative Democratic senator, Mary Landrieu, was “printing money like there’s no tomorrow” and “making everything cost more for average people like me.” Misrepresenting an opponent’s record may be the kind of thing even official campaigns do when they can get away with it; but pandering to the unhinged fears of Paulites and gold bugs is exactly the kind of move you make when you figure no one is looking.

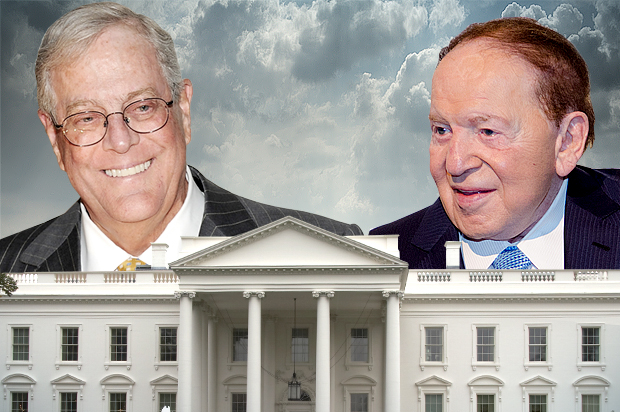

The Times being what it is, the partisan angle of the story is underplayed; a not-so-discerning reader would be forgiven for concluding these kind of shady dealings were the fault of “both sides.” Yet although the Times is able to find at least one pro-Democrat super PAC to cite — and despite the fact that I’m sure it’s just one of many more — the clear preponderance of super PACs and dark money is being directed by and on the behalf of conservatives and Republicans. As close observers of campaign finance have long predicted, the right is more than making up for whatever nominal advantage Democrats had this year in above-board financing by relying heavily on these shadowy funds. And as any follower of American politics over the past six years would expect, the Koch brothers are heavily (but mysteriously) involved, with one former Koch executive running one super PAC, while others in the Koch universe are no doubt connected to many more.

So with Election Day finally upon us, take a moment to turn on your TV and radio, or to ignore your caller ID and pick up the phone. Immerse yourself in the reality of American politics in the Citizens United world and start getting used to our democracy’s newest tradition. Watch in October and November to see the final bids in the auction for the U.S. government; then tune in again in early 2015 to find out which members of the one percent actually won.