“Vocabulism” is a Salon series about how the Internet is killing the English language, one word at a time.

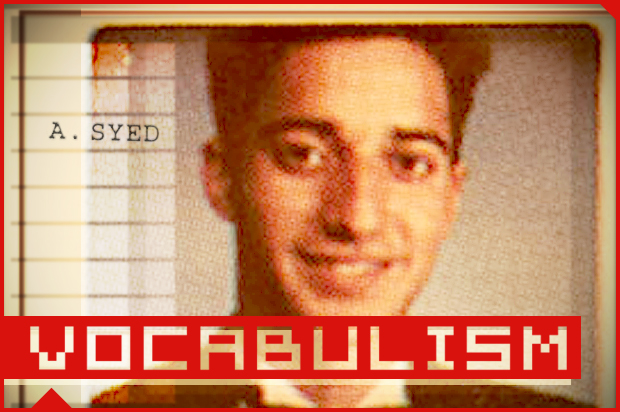

Once upon a time, in a land not so far away, “storytelling” was reserved mostly for kindergarten teachers and campfires. But in 2014, storytelling is everywhere. It long ago infiltrated the world of comedy; storytelling shows dot the schedule of tastemaking venues like Upright Citizens Brigade, and you can take classes on the subject from New York to London. The Moth, the hugely successful storytelling series, has become a mainstay of the live-performance scene in cities across the world over the past decade. In the increasingly fractured world of journalism, editors and writers are turning to new narrative methods to entice flighty readers. And the narratively ambitious new podcast “Serial,” a spinoff of “This American Life,” is dominating dinner conversations, at least in Brooklyn.

The problem is that the definition of “storytelling” has never felt emptier. Everyone from mealy-mouthed online marketers to self-help gurus have taken note of the sacrosanct place “storytelling” holds in our culture — and they’ve kidnapped it, roughed it up and deposited it on a one-way train to buzzwordsville.

[embedtweet id =”528218421436379136″]

As we’ve been told again and again, by everyone from scientists to political scientists, humans are instinctively drawn to structured narratives. They crave beginnings, middles and ends; they try to piece together plots from events even when the truth doesn’t conform to any dramatic type; and they disdain uncertainty. Part of the appeal of looking at the world through a neat narrative lens is to retain the illusion that the world is somehow ordered, not just scarily chaotic. (This explains, in part, people’s feverish desire to “solve” mysteries, from the ending of “True Detective” to the whereabouts of the Malaysian plane.) Pop culture has certainly complied with this primal craving of late; the golden age of television has gifted us a landscape lousy with plot-rich prestige dramas. Superhero mega-franchises dole out prequels, sequels, spinoffs and origin stories, all at the service of the familiar arcs laid out by comic books. Serial’s true-crime twists and turns have made obsessives out of listeners while predictably inspiring a mini-cottage industry of speculators eager to ferret out the truth.

If you search, say, Twitter for “storytelling,” you’ll find something a little more pedestrian: an endless parade of articles focused on the art of the sell. There are titles like “The Death of Branded Content — The Rise of Brand Storytelling.” There are reminders that “Only good storytelling can drive social engagement.” And much, much more.

[embedtweet id =”530328015218438146″]

[embedtweet id =”530324075085045760″]

[embedtweet id =”530296487167934464″]

[embedtweet id =”530328785996902402″]

[embedtweet id =”530325825972088832″]

Ad agencies are hardly the only offenders. I recently received a P.R. pitch informing me that “for the first time in real estate history, Coldwell Banker is empowering sellers to be actively involved in marketing and telling the story of their home.” (This is thanks to a new app where you can regale prospective sellers about your residence’s history while presumably ignoring any murders that may have occurred there.) One of the benefits of this personalized style, according to the pitch, is that “buyers get the benefit of transparent and authentic information from the seller.”

That idea, I think, lies at the heart of storytelling’s bastardization. In an era when discerning consumers expect everything from their food to their celebrities to retain the whiff of authenticity, “storytelling” connotes something pure and unfiltered. When we invoke storytelling instead of “writing,” “marketing” or “selling,” we’re tapping into an ancient code of behavior that seems more rooted in shared experience, more fundamentally human, than mere marketing-speak. “

There’s also an assumption that by merely saying it, you’re guaranteeing the importance of your own message. It has become a get-out-of-jail-free card to illustrate that whatever it is you’re peddling can’t be craven, or hacky, or even boring. It’s storytelling, so it’s essential. But the truth is that storytelling is subject to the same limits as one-liners, listicles or any other form of modern creative expression. There are good stories and bad stories. Yet given how pervasive the storytelling label has become, even masterful narratives like “Serial” seem somehow flattened by it.

[embedtweet id =”530502447760814080″]

[embedtweet id =”530396699630776320″]

[embedtweet id =”527957487925071874″]

[embedtweet id =”527799169071976448″]

It’s a tall order, and surely a bad idea, to excise “storytelling” from our vocabularies entirely. The most we can ask for is a simple awareness of its limitations. Let’s try to return “storytelling” to a place that more suits its cherished childhood status, and less suits corporate gobbledygook.

[embedtweet id =”528226357315379200″]

And we all lived happily after. The end.