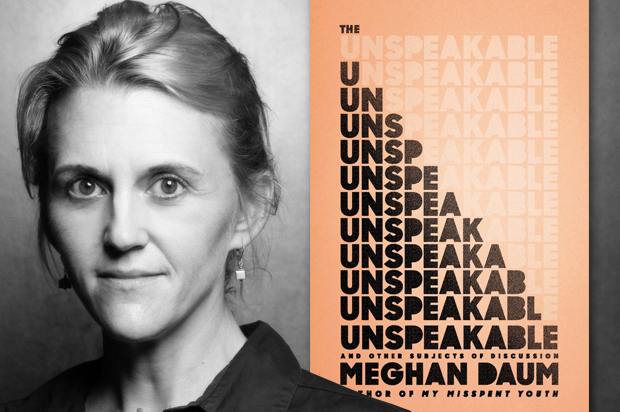

I had not heard of Meghan Daum until I read her September profile of Lena Dunham in the New York Times. (I thought that Lena Dunham was always fraught territory, but September, it turns out, was positively prelapsarian; Lena Dunham coverage only had to address the issue of whether she is an overexposed hack, and not, as now, whether she is a child molester.) In any case, I came away thinking that this Meghan Daum had done a masterful job with the profile, which managed to be both fair to Lena Dunham and to make me interested in reading, not just the thing that Lena Dunham had written, but the things that Meghan Daum had written (and probably more of the latter). In the lazy millennial’s sincerest form of flattery, I Googled her, and followed her on Twitter. When, shortly thereafter, I read an essay from her new collection, “The Unspeakable,” in the New Yorker, I checked her old books out from the library and obtained an advance copy of the new one.

In Daum’s profile of Dunham, she writes that “there’s a very good argument to be made that there are too many people, young women especially, writing about their personal experiences these days and not enough willing to report from the battle lines that exist outside their own heads.” She goes on, though, to defend Dunham’s collection against the inevitable accusations of solipsism and pointlessness, pointing out that Dunham is 28, and describing what Nora Ephron, Joan Didion and Dorothy Parker were up to in the same year of their respective lives: “None of them at that point had totally found their way to the issues that would come to define them. And despite the monumental platform Dunham has been given, that’s probably true of her too. She’s everywhere, but she’s still not there yet.”

Daum’s first essay collection, “My Misspent Youth,” was published in 2001, and collects essays written when she herself was in the same chronological vicinity as Dunham is now. And while Daum cannot be said to have been “everywhere” in the Lena Dunham sense, as a writer, she was in a lot of the places you want to be: the New Yorker; the New York Times; GQ. In light of her remarks on Dunham, it is instructive to read those earlier essays alongside “The Unspeakable”; with her new collection, it seems that Meghan Daum is here.

In a quasi-recent piece for the Believer on the “haterade” that characterizes online discourse, Daum revealed that as an MFA student in the 1990s she “set aside the fiction I’d gone there to pursue and began writing personal essays. Things started clicking almost immediately and a central theme emerged: the relationship between myself and society, the tension between the trappings of contemporary life and the actualities of that life … And, as is always the case for a young writer, every experience I had … was potential fodder for another piece of groundbreaking, human condition–explaining nonfiction.” Daum was poking fun at herself, but her output over the course of her career thus far has borne out her 20-something’s instincts; I never thought I would enjoy an entire book about one person’s singular and occasionally deranged relationship with rental properties and real estate, but I loved “Life Would Be Perfect if I lived in That House,” Daum’s 245-page book on that subject.

The specter of the confessional haunts all first-person writing, and women’s writing in particular. Daum’s Dunham profile was called (although perhaps not by Daum) “Lena Dunham Is Not Done Confessing.” Daum insists in her own introduction to “The Unspeakable” that the essays therein, “frank as they are,” aren’t confessions: “While some of the details I include may be shocking enough to suggest that I’m spilling my guts, I can assure you that for every one of those details there are hundreds I’ve chosen to leave out.” Meanwhile Leslie Jamison, another essayist who seems “everywhere” these days, freely assigns the “confessional” label to her own lauded collection of essays, “The Empathy Exams.”

I am committing a female hate crime by mentioning Daum and Leslie Jamison in the same essay, since to mention two women in the same profession is always to set them against one another. But when the New York Times asks us to consider whether we are in “the golden age for women essayists,” and its jurors mention them both, it’s hard not to. And while it is dramatically different in its execution, Jamison’s work is situated right in the nexus that Daum identified as motivating her own early work — the “relationship between myself and society.” Some of Jamison’s essays in “The Empathy Exams,” like the barnstorming “Devil’s Bait,” an essay on Morgellons disease, are rooted in traditional reportage, but they always circle back to the meaning that these topics assume against the backdrop of Jamison’s own life (and often, her own privilege).

In some cases, the outside-world things that Jamison writes about (like Morgellons) are interesting enough that I could have done without the self-reflection, not because it seemed self-indulgent exactly, but because it seemed superfluous, simultaneously overwrought and apologetic (two traits that I fully realize are typically ascribed to women by people who don’t like women). Jamison has an elegant answer to my critique in her own text, in an essay about cutters called “Grand Unified Theory of Female Pain”: “A cry for attention is positioned as the ultimate crime, clutching or trivial — as if ‘attention’ were inherently a selfish thing to want. But isn’t wanting attention one of the most fundamental traits of being human — and isn’t granting it one of the most important gifts we can ever give?” In the same essay, Jamison critiques the characters in Lena Dunham’s show “Girls” for their callousness: “These girls aren’t wounded so much as post-wounded … They’re over it. I am not a melodramatic person. God help the woman who is … The post-wounded posture is full of jadedness, aching gone implicit, sarcasm quick-on-the-heels of anything that might look like self-pity.” Post-wounded women “guard against those moments when melodrama or self-pity might split their careful seams of intellect.”

Jamison seemed apologetic to me in her frequent reflections on her privilege, but in the larger sense she is unapologetic about the act of writing what is deeply personal, unapologetic about feeling pain and telling us about it. “Grand Unified Theory of Pain,” in fact, had me apologizing at the end for being such a judgmental bitch.

Daum’s essays, particularly in her 2001 collection, “My Misspent Youth,” are often unapologetic in a different vein, to the extent that they are sometimes unsympathetic — like “American Shiksa,” a cheap-shot-laden riff on WASP women who love Jewish men, or “Variations on Grief,” a provocative account of a friend whose only notable characteristic, in Daum’s telling, is the fact that he died at age 22. “Life Would Be Perfect if I lived in That House,” which I read while thinking a lot about my own living situation in a crazed real estate market and which thus resonated profoundly, is a portrait of a possibly mad person with more money and gumption than sense, and that’s why it is so great.

Meghan Daum may be unapologetic in her writing, but this does not mean that she is absent the urge to explain herself. In the beginning of her new collection, an explanatory introduction that in fact feels unnecessary given the quality of the essays, she gestures to the idea that personal writing is a dime a dozen, an echo of her Dunham profile: “In some respects, serving as my own main subject has been a great convenience … In other respects, though, it feels lazy.” Eventually, though, she concedes that “for all my ambivalence about mining my own life for material, I can’t seem to quit for very long … the work that seems best remembered … is the work in which the ‘outside world’ forms a vital partnership with that I narrator.”

Daum is so good at describing that “vital partnership” in a warm, humane way that I enjoyed even those pieces that dealt with topics, like Joni Mitchell, that don’t particularly interest me. And there are three unforgettable essays in “The Unspeakable”: “Matricide,” “Difference Maker” and “Diary of a Coma,” which are the first, central and last essays of the collection, the most serious in terms of subject and tone (and, incidentally, the ones that veer closest to Jamison territory).

“Matricide” is an account of the death of Daum’s mother, throughout which thrums a tightly controlled note of grief and long-harbored rage. The essay swoops from her mother, to Daum’s own near-death experience, to a miscarriage, closing the circle of these experiences in a haunting and lovely way: “Of course it was a girl. It was a girl and of course it was dead, another casualty of our fragile maternal line, another pair of small hands that would surely have formed furious fists in the presence of her mother.” “Difference Maker” casts Daum’s ambivalence about children against her experience advocating for children in the foster system. While ambivalence about children among women nearing the end of their most fertile years seems to be a popular subject for the essay lately, Daum manages to expand the scope to illustrate the profound gulf carved by class and luck in our society. “Diary of a Coma” describes Daum’s experience of an illness, one during which she lost her speech and, nearly, her life: “‘How many fingers am I holding up?’ the doctor asks. I can answer that. That one’s easy. Still, there are things that I know and things that I don’t. What I know is that I’ve never felt sicker in my life. Moreover, I’ve never felt this kind of sickness. It’s as if my life is draining out of me and pooling at my feet. What I don’t know is the degree to which that is in fact an accurate impression. Technically, I am dying.”

Jamison’s essay on female pain; Daum’s simultaneous disavowal of the confessional and embrace of the personal has me wondering whether the “golden age of female essays” isn’t the unlikely but happy result of two contradictory currents in women’s experience: In a sense, personal writing is both an expression of bravery — a rejection of shame — and a socialized female obligingness channeled into art. After all, what is more presumptuous than to put someone else’s words and experiences onto the page? Placing yourself in the picture, even if it’s someone else’s picture, forestalls the rudeness of presuming to opine; making yourself the whole picture evades the problem altogether. Subjectivity isn’t self-indulgent — it’s polite. It is demonstrably impossible for me to write any piece of criticism and not make a cameo therein, and while I admit to being as self-involved as any special snowflake with an Instagram account, often the instinct to insert myself comes from a place of saying, “I’m not an expert, I’m just a person; let me show you where I’m situated here in this thing I’m telling you about.”

I don’t have any proof of this theory, it’s just an idea. But just to show you where I’m situated here, one of the things I love about Daum’s new collection is that it demonstrates how a talented writer gets even better, how her craft can grow along with her body of experience, how the “vital partnership” between the “outside world” and the “I narrator,” like a marriage, can improve with age. In her 20s, Daum wrote great essays. In her 30, she wrote a good-not-great novel (“The Quality of Life Report”) and a wonderful memoir-cum-real estate guide. And she keeps getting better. It seems appropriate, but not quite just, that Daum should be writing profiles of today’s hot young talent; as far as the essay is concerned, the younger cohort should be signing up for her master class. I know I’d like to.