When an onlooker saw Tamir Rice holding what appeared to be a pistol at a Cleveland playground, he called the police. He told the dispatcher, “I’m sitting in the park … there’s a guy here with a pistol, and it’s probably a fake one, but he’s pointing it at everybody.”

The caller was right that it was “probably a fake one.” Rice was holding a BB gun. But he was wrong about something else. Rice wasn’t a “guy,” he was a 12-year-old boy. He was a child when police shot and killed him on Saturday afternoon.

Rice was killed two days after police shot and killed Akai Gurley, who was walking down a darkened set of stairs in the Brooklyn building where he lived when he an encountered an officer who had his gun inexplicably drawn.

Gurley was killed as crowds continued to gather in Ferguson, waiting to hear if a grand jury would compel a white police officer to stand trial for killing Mike Brown, who was unarmed and shot dead at 18 years old.

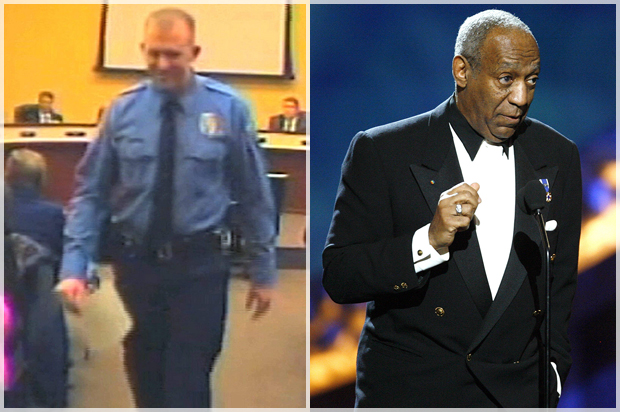

All the while, there was more news about a man who is alleged to have raped nearly 20 women. More women came forward last week and over the weekend to say that they had been drugged and raped by Bill Cosby. That they had trusted him as a mentor and in return had their bodies used and discarded.

The histories and contexts here are all different, but when I think about these stories, each stands as an example of profound human ugliness. Of the cruelty and indifference that individuals are capable of, and the racist and misogynistic systems that prop them up, condone and foster that cruelty.

Each time we are told there is some lesson to be learned. Some mistake that won’t be repeated. Some truth or deeper knowledge that we now have, so that maybe things can be different.

And this is true, of course. There are lessons. And teachers.

The parents of Mike Brown and Tamir Rice have joined a devastatingly long list of families demanding accountability for their loved ones and exposing a brutal pattern of racist police violence. Protesters in Ferguson and across the country have kept these stories alive to a public that is too often indifferent and distracted. And the women who are coming forward to share their experiences of violation at the hands of a powerful man are making their voices heard so that the voices of other victims might also be heard.

In their words and actions we are compelled to talk about white supremacy, about the violence of the state, about the silencing of rape victims, about the normalization of sexual violence, about rape culture, about how these systems interact and are reinscribed in ways large and small.

But these are lessons that far too many of us just don’t learn. We don’t learn them again and again and again.

We see the same scripts play out. We will likely hear the same questions about Tamir Rice that we heard about Mike Brown, Jordan Davis, Renisha McBride, Trayvon Martin. Was he a good kid? Why did he have that pellet gun? And we continue to hear the same ugly, humanity-denying contrarianism in defense of Bill Cosby that we have seen degrade victims and prop up abusers many times before. Why didn’t they all go to the police? Aren’t these just social climbers? Why would they want to exploit a good man?

And this is where I am stuck this morning. In the pain of all of this pain, and the pain of knowing that we will see more of it. That it will look and sound familiar because it will be familiar. Because we just haven’t learned yet, or haven’t learned enough.

When I think of what we still need to learn, I’m thinking of the words of Stacia L. Brown, whose mournful reflections on Rice remind us that he was a real child, more than a name on a page or a number on a terrible list:

We will never know what you were thinking, if you had time to think. We’ll never know exactly how afraid you must’ve been. You, specifically. Tamir E. Rice, twelve-year-old boy who died the day after being shot by police at a playground in Cleveland. You, whose eyes in the first photo released to the public, are soft and kind and so age-appropriately childish, the kind of eyes that couldn’t have known what else to do with a toy gun than play with it. We will never have the privilege of knowing you as anything other than teary anecdotes, than memories offered up to the court of public opinion as closing arguments.

And the words of Roxane Gay, who reminds us that the victim of a brutal assault at the University of Virginia, a young woman called “it” by her rapists, was a real person who deserves to be believed. Just like the millions of women and girls whose names and stories we do not and will never know:

Too many of us have been “it”. Too many more of us will become “it”. Too many of us will continue to look anywhere but at the ugly truth. […]

This is the ugly truth. Rapists make us less uncomfortable than rape victims. Predators demand so much less than victims; they aren’t as inconvenient. They don’t bleed or hurt or reveal their gaping wounds. If we don’t doubt them, we do not have to doubt ourselves. […]

“It”.May we be haunted by that word and the woman who was forced to bear it until she, and every rape victim, is seen, heard, believed.

There are institutions that must be taken apart and remade and replaced. There are vocabularies of violence and history we have to learn rather than reflexively dismiss. But these lessons are also sometimes quite small. They ask that we remember the names of the lives lost or lives changed forever. To remember them as people with ambitions, failures, embarrassments, loves and all of the other messy and imperfect trappings of being a person.

But it seems this is the lesson so many of us keep missing. That our country is so very cruel to so many in a pattern that we recognize, in a pattern that can be stopped.

It seems that our culture has never been more aware of racist police violence, and yet we are asked to treat each new incident as an isolated case rather than a harrowing pattern. Particularly among white Americans, we are silent in the face of yet another death of a young black kid. Instead of asking why officers use deadly force with impunity, we ask why a kid had a BB gun, why another kid wouldn’t turn his music down, why another kid wouldn’t just get on the sidewalk like he was told.

We are once again talking about the very human imperative to believe women who have come forward about violence that one in five women will experience in their lifetimes, and yet we continue to doubt. To question women’s “motives” for coming forward, to ask why they didn’t report sooner, or why some never called the cops.

We ask these questions even though we know the answers, we just refuse to accept them. But still, they are staring us in the face, pointing to all of us, asking, When will you have had enough?