This week, millions of Americans will face the prospect of cooking Thanksgiving dinner without a very clear sense of how to do it. How often do most of us roast a turkey, anyway? About twice a year on average is my guess, a fact that suggests we’re a lot less enthusiastic about the national feast bird than we claim. Some of these unpracticed chefs will pull out a gravy-stained recipe handed down by an older and more oven-savvy female relative. Others will open a classic kitchen bible like “The Joy of Cooking.” Still others will try something different, to the predictable displeasure of their tradition-loving family and friends. And many — upward of a million if we judge by subscriber rolls — will turn to the very wonkiest of kitchen authorities, Cook’s Illustrated.

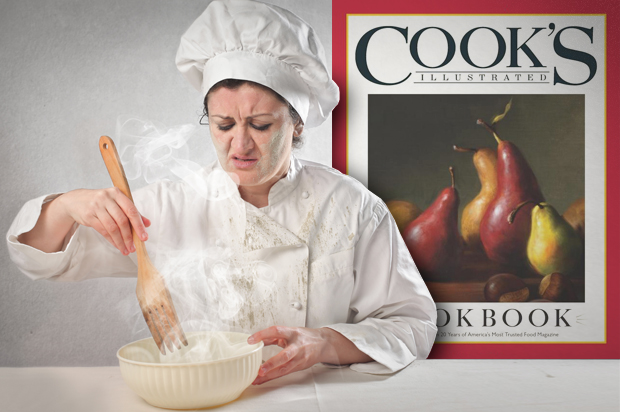

Based in Brookline, Massachusetts, the Cook’s Illustrated empire comprises a magazine published every two months, a series of cookbooks with titles like “The Best Recipe” and two television programs on PBS, “America’s Test Kitchen” and “Cook’s Country.” There are admirable things about all of these enterprises, particularly the lack of advertising and therefore the unlikelihood that Cook’s Illustrated will ever present you with an ingredients list containing an item like “1 10-oz. package of Nestle’s Toll House Butterscotch Morsels™.” I would not go so far as to say that Cook’s Illustrated is never a force for good in the kitchen. Nevertheless, Cook’s Illustrated’s undeniable failings cry out for remonstrance: Simply put, the magazine takes all the soul out of cooking.

In the interest of fostering a world in which all peeved cooks can tell their stories, here is my own: As someone who subscribes to a couple of cooking magazines, I often get samples of others sent to me in the mail. This is how I happened to be leafing through a copy of Cook’s Illustrated and came across a recipe for roasting artichokes, a vegetable I love but usually find too much of a hassle to prepare. Since Cook’s Illustrated presents itself as a quasi-scientific enterprise in search of the supreme version of every dish — and, furthermore, it promised that roasting is “the best way to cook artichokes” — I did what most home cooks do when stumbling across an appealing recipe in one of the leading journals of our times: I tore out the page and tossed the rest of the magazine in the recycling bin.

A few days later, I arrived home with a bag full of the giant, edible thistles. (Yes, artichokes are a thistle.) I cleared the counter, got out a sharp knife and propped up the clipping. To my dismay, the article, which I naturally assumed to be no longer than a page, was cut off at midpoint with no recipe in sight. As I would eventually discover, after hunting up another copy of the issue at a friend’s house, the author of “The Best Way to Cook Artichokes” did not actually get around to telling his readers how to cook artichokes for another page or so — a page I had neglected to tear out along with the first. All told, the story consisted of a concise-enough recipe preceded by 2,000 words of superfluous blather. (How do you think I learned about the thistle thing?)

Now, I admit, as aggravations go, this is a really, really petty one. But I also know that I’m not alone, most particularly in my belief that there is no need for a sentence like “Those factors also compelled me to skip uncovered roasting tests, during which the artichokes would dry out, and start with a hybrid steaming-roasting technique that we’ve applied to other roasting vegetables” — let alone references to “the flavorful Maillard browning reaction.” For the love of God, just tell me how to roast the frigging artichokes — and be quick about it.

And yes, I admit, I’m an impatient cook. One of the least-touted but most advantageous skills in a person seeking to survive as a professional writer is the ability to cook upward of 95 percent of one’s own meals from scratch. This can save you a fortune on takeout, prepared foods and restaurants. But when you cook as much as I do, you don’t have much time or tolerance for the rhapsodies of the true foodie, those people who claim to adore reading 12-pound, glossy-paged molecular-gastronomy cookbooks in bed “like novels.” Likewise, the exhaustive scholasticism of Cook’s Illustrated, which feels obliged to inform you of every chemical interaction involved and to supply a blow-by-blow account of the long process of trial and error by which the magazine’s staff arrived at the platonic ideal of a particular recipe. Cut to the chase, please.

Besides, there is something pitifully reductive about the notion of the best or perfect version of a dish. Should a slice of bacon be chewy or crisp? Should the meatballs in a spaghetti sauce be larger or smaller than a pingpong ball? How soupy do you like your Thai green curry? There is no definitive answer to any of these questions, even when it comes to baking, the most precise of the culinary arts. There are certain states in the union where advancing the wrong kind of cornbread (sweet or savory) as the paragon of its kind can get you into a nasty spatula fight.

My colleague Mary Elizabeth Williams concurs. Unlike me, she once subscribed to Cook’s Illustrated, mostly in a plaintive quest for narrative tension. “I used to love the mystery plot of the magazine,” she told me. “WHAT WOULD THE SECRET TECHNIQUE/INGREDIENT BE? I can’t believe it was melba toast!” But then disillusionment set in. “Every recipe would start, ‘We wanted to make something that didn’t have too much flavor!’ I’m not Guy Fieri, but I like cooking to be more fun and improvisational. There’s no passion in Cook’s Illustrated.”

This is partly the result of cooking by committee. The dish that passes muster with everyone, like the book that wins a literary prize, is most often a compromise candidate. No one truly loves it to distraction. My biggest complaint with Cook’s Illustrated, after its prolixity, is that the dishes it teaches you to make are boring; I can’t get excited about pot roast, even if it is the ultimate pot roast. As Mary Beth observes, cooking ought to be expressive and personalized, catering to the idiosyncratic preferences of the people who’ll be eating the results. Isn’t that the point of home-cooked meals? Furthermore, diners are mutable. Some days you want your split pea soup to be rich in ham hocks and other times you’d rather go veggie.

Some will argue that Cook’s Illustrated is not intended for the likes of me and Mary Beth. Instead, it’s for those who feel unconfident in the kitchen, who cook rarely and who worry about ruining the meal by making some tricky minor mistake. If there are people who take comfort and find success in the micromanaged approach of Cook’s Illustrated, then of course I congratulate them. Also, I freely confess that I have found some good tips on the magazine’s website. Still, when I look at a bloated story like “The Best Way to Cook Artichokes,” I can’t help thinking a certain mystification is at work. Cooking artichokes, whatever method you choose, is just not that complicated. It does not need to be approached as if it were the categorical imperative of Immanuel Kant.

Isn’t it just as likely that the excessively detailed and elaborate instructions in Cook’s Illustrated perpetuate the idea that cooking is a dauntingly complex process in which pitfalls await at every turn? The truth that cooking is also forgiving and that it permits and encourages creativity gets lost. There are times when the Cook’s Illustrated approach seems almost pathological, a form of OCD in the face of what is a fundamentally unpredictable, even chaotic practice. You may be able to robotically reproduce each step in the magazine’s algorithmic series of recommended actions, but your ingredients may differ significantly from those used in the famed test kitchens — food is erratic, organic material, after all — and who even knows what the deal is with your oven. Ovens can be eccentric, and since you hardly use yours, how can you possibly have learned to account for all its little ways?

When it comes to Thanksgiving, however, the common recourse to Cook’s Illustrated is understandable. With 13 people coming over and every shop in town closed for the holiday, no cook can afford to take chances. Preparing Thanksgiving dinner is much like drafting a wedding invitation; you rely on authorities for a template because, god willing, you’ll never acquire enough experience at it to become an old hand. But do yourself a favor once the table is cleared and the fridge packed with leftovers: Move that copy of Cook’s Illustrated or “The America’s Test Kitchen Family Cookbook” to the back of the shelf and invite a more stimulating mentor into your kitchen — whether you call him or her Marcella or Ina or Bittman or Nigella — instead. Sure, they’re not perfect, but then, who is?