For much of the past six years or so, U.S. policy in the Middle East has had a “Godfather III” problem, with the recent (and strangely ignored) news that the war in Afghanistan won’t be ending in 2014 after all as just the latest example. After a decade-plus of invasions and occupations, an American military presence in this, the most volatile region of the globe, has become a given — like overcast skies in England or earthquakes in Japan. It can be hard to remember at times that what brought the U.S. armed forces to the Middle East initially was not fate or inertia but terror, and the desire to vanquish it by winning a global war.

But while America’s use of drones in the Obama years has made the difference between wartime and peacetime even fuzzier than the Bush administration had already, the fact is that in Iraq and Afghanistan, where the war on terror’s two most conventional military campaigns took place, war was not an open-ended proposition. There were goals, objectives; a beginning and an end. And according to the new book by retired three-star Gen. Daniel Bolger, “Why We Lost: A General’s Inside Account of the Iraq and Afghanistan Wars,” these wars finished as impossible missions left incomplete.

Recently, Salon spoke with Bolger over the phone to discuss these poorly conceived wars, why he blames himself in part for their outcome and what America must do if it hopes to never make similar mistakes again. Our conversation is below and has been edited for clarity and length.

So before I ask you how we lost the wars, I want to ask you how you define winning? Part of what made these wars so distinctive, I think, is how that question was never really answered, in spite of all the years.

That’s absolutely right, and the very fact that we have that conversation is a real caution as to we cannot be too quick to jump into these things. From the ’80s, the Weinberger Doctrine — sometimes called the Powell Doctrine, after Gen. Powell — [said], “Hey, when you go into something, you’ve got to have a clear idea of an end state.” Of course, it’s easy to say that, but it’s really hard to do it; and I think that’s probably as it should be, because war is not something to be entered into lightly.

In the wake of 9/11, we had an almost national consensus that something needed to be done about al-Qaida. What needed to be done and for how long, we never had that discussion until we were well down the track … The old adage of look before you leap absolutely applies in wartime. The American tradition is war as a last resort, and I think there’s good reason for that.

All right, so, what’s the answer to the big question? Why did we lose?

We lost for the two most fundamental reasons you can lose a war. Right out of Sun Tzu, the ancient Chinese master, who wrote “The Art of War” centuries ago — what did Sun Tzu say? He said that if you want to be victorious in war you must know the enemy and know yourself. If you know only one, you’re .500. If you know neither, you will lose. In our case, we managed to have a problem in both areas.

We didn’t really define our enemy. I mentioned Gen. Powell already, and he was one of the few guys in the Bush cabinet who said, “Hey, who’s the enemy here? It’s al-Qaida.” So defining that enemy and going after that enemy was something we had a lot of trouble with right from the outset because al-Qaida was being hosted by the Taliban, the government of Afghanistan. We got into it with a whole bunch of Afghans who had never attacked us and, in fact, most of the casualties we’ve suffered and inflicted in Afghanistan have been related to the Taliban, not al-Qaida. We certainly went after [al-Qaida], but the bulk of the fighting we’ve done over there has essentially been with a local group that, odious though they may be, had never threatened the United States or done anything to us.

To expand that war and go into Iraq, Saddam Hussein — again, a bad guy, done bad things, terrorist activities that he’d sponsored, killed a million of his own people, used chemical weapons in massacres of villages and invaded the neighbors — no doubt about it, a bad guy. We were engaged with them with aerial campaigns, which is a nice euphemism that basically means we’re flying over the country and bombing them on a periodic basis when they’d shoot at our plane. Does that mean, OK, we’ll dive into that country and mix it up with a bunch of Sunni Arab insurgents who, again, had never attacked America but were pretty excited when we showed up on their doorstep?

That’s the first part, not defining the enemy and letting the problem-set really expand. As a military guy, it’s hard enough to fight the enemies you need to fight. You don’t need extra enemies, especially when those enemies are wearing civilian clothes and mixed into villages, which is the hardest type [of warfare] to get into when you’re a soldier, because we’re built to fight conventional, short wars. We know that things like Vietnam don’t work, and that gets us to the second point of the old Sun Tzu warning: know yourself.

Our self is a volunteer military built since the Vietnam War to fight short, decisive operations. Things like Kosovo in ’99 or Iraq in ’91, Desert Storm-type things; that’s the type of war we’re built for. You put us on that type of mission, we’re great. You back us into a situation in an unfamiliar culture where we’re going from door to door trying to figure out which guy in civilian clothes is a farmer and which guy is an insurgent, you’re putting us on a road to an endless, endless stalemate. We don’t have enough refinement to figure that out and we’ll never get the support of the local people because we’re outsiders.

That’s basically what we did. We didn’t understand the enemy and we overestimated our own capabilities because we had these smashing early successes. Hey, we got great men and women in our military and they can do a lot of things — but they can’t do the impossible.

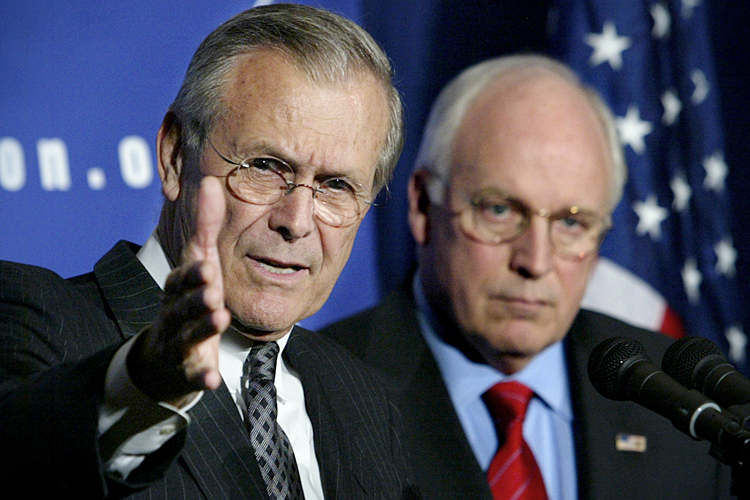

If memory serves, Rumsfeld himself, when he was selling the war, said it would be quick and easy, right? He presented it as being along the lines of Kosovo ’99 or Desert Storm.

You’re exactly right, but that was the war we wanted to fight. We didn’t take into account that there was an enemy who would also have a war they wanted to fight.

To go back to that opening month of the war, March of ’03, the first few weeks when our forces were driving on Baghdad, you might recall there was a period where there was a sandstorm. That kind of stuff comes up in that part of the world, and it messed up our air support and caused us to halt for a little bit and change what we were doing. While we were marking time for a couple days letting the weather blow over, Gen. Scott Wallace, senior field commander at the time for the army troops on the ground, made a comment to some reporters that, “Hey, this is a different enemy we’re fighting from the one we expected.”

What he was getting at was that we’re not having a hard time fighting units like the 11th Iraqi Army Division but these Fedayeen Saddam guys in civilian clothes that are popping out of the woodwork and shooting our convoys and all that. Gen. Wallace knew what he was talking about because he had fought in Vietnam. He got sort of slapped around for saying that …

[He was] right … warning us of what we were running into, but a lot of people didn’t want to hear it because the smashing victory against the Iraqi army is what they wanted to hear about. And that did occur, but then we stayed and backed into the counterinsurgency.

What do you think is the biggest misconception still about these wars? That the surge worked? (And, again, we need to define what “worked” even means.)

I certainly agree that the idea of the surge is also definitional. The surge, by its nature, was going to work. But just like the word says, it was a surge; it was temporary. It’s like a wave coming over the shore and then receding back into the ocean. In a temporary sense we sent in a lot of troops, we went out and secured the countryside, we killed a lot of bad guys … but there’s a clock on that. A surge just gives you temporary relief. It’s good while it lasts, but it’s not going to stay.

Look, we were fighting a guerrilla enemy. Mao Tse-tung had defined what guerrillas were doing for centuries before he wrote it down, but he basically said the guerrilla ethos: The enemy advances, we retreat; the enemy retreats, we advance. They’re going to wait us out, and this should not have been news to Americans. That’s the nature of an insurgent enemy. We had fought insurgents before! Heck, we had been insurgents ourselves in 1775-1783, when we fought the British. We know this method, and that’s why I really fault myself and the other military leaders for missing that …

That brings me to something I wanted to ask you about, which is the review the book got in the Times from Andrew Bacevich —

Of course, like most people who write books, you hope that someone will review it who’s got some stature and credibility — and he’s got all that … I think he raises some good questions. I will tell you right now, I claim no special insights beyond what I saw in the Army as to the machinations of the Joint Chiefs of Staff or what goes on in Washington. The field stuff I do know about, and that’s what I mostly cover. I’ll leave the Washington stuff to folks like Bob Woodward who know that stuff better. I know what I know. But I thought professor/Col. Bacevich was very fair, and I think he correctly raised the overall issues raised by the book. He’s been raising them himself in his own writing for years.

My sense was that, if anything, he thought you were too hard on yourself.

He’s kind to say that, but he also knows, as a former commander himself, that I feel a responsibility for the people I lost and for the missions I wasn’t able to accomplish. The U.S. Army says that the commander is responsible for everything a unit does or fails to do — and that authority is absolute. The Navy has the same rule. No matter what you’re doing, if your ship runs aground or bangs into another ship or gets sunk because you weren’t alert, the captain of that ship is responsible. We need that degree of responsibility and accountability in the military …

To return to the surge, I recall that Gen. Petraeus, when he was pitching the country on his plan, described it as a more sweeping change of U.S. policy than just increasing the number of troops. From today’s perspective, how do his comments about a more thorough reboot hold up?

Not just from Gen. Petraeus. Obviously, he’s the commander, so he’s the face of it; but a lot of people thought that this U.S.-led counterinsurgency with the addition of troops would reinvigorate things …

A manual was written for the Army and the Marine Corps with Gen. Petraeus as one of the guiding lights of that, and there was a lot of talk about this counterinsurgency. We’re going to do this, we’re going to do that, lessons learned from past counterinsurgencies, etc. — all codified in a written document. From what I saw (and I was in the country before Gen. Petraeus arrived, I was there for almost 17 months in ‘05-06, during what would be the run-up to the surge) all the stuff being described in that manual was stuff that was already being done. There’s nothing wrong with that; the theory is correct. But the fundamental flaw is that it can’t be done by the Americans or any other foreign power.

Those techniques had to be done by the Iraqis, and as long as the Americans were there to the tune of over 100,000 [troops] … I can’t blame them for stepping back and saying, “Hey, you’re the best army in the world; you go do this and we’ll watch.” That’s a fundamental flaw in the approach, because it had to be carried out and won by the Iraqis, supported by us.

The surge actually delayed that Iraqi pickup and, as we saw when ISIS came into the picture in a big way, the Iraqis weren’t ready for it. That’s totally predictable; they’d only been working with us for a few years and they’d been designed to function alongside us as auxiliaries. You pull us out of the equation and the Iraqis go back to their ways that we saw in ‘91 and in 2003 — and they’re not a very good army.

Does your intimate knowledge of the Iraqis’ capabilities (and lack thereof) lead you to worry that the “no boots on the ground” promise won’t be kept?

We shouldn’t be surprised that the Iraqis, with only eight years where we were really working hard to build their military, weren’t there yet. By analogy, in the Korean War, the South Korean army, which we had been training since 1945, five years later, when the North Koreans invade, they fall apart and we have to come in and help them out. A decade and a half later in Vietnam, they’re an OK army and they can function on their own without American help. Nowadays, they’re a very good army, which is decades and decades later. It took them a long time to build their military schools, their leadership selection systems, all that kind of stuff, with our help and our guidance. And that’s what it’s going to take in Iraq; that’s what the president is talking about in terms of us being in a training and advising role rather than leading.

Another thing about “boots on the ground” is that the reality of the 31,000 Americans over there is that unless they’re in a hovercraft or something, they’re on the ground. They’ve got to be somewhere. I think the thought is that it’s not the Americans who will be doing the firing and maneuvers; that’s an Iraqi job. We’ll be helping them but they’ve got to do that, and I think that is a lesson learned from this war in both theaters. Americans can’t do it for them, and if we try to, we feed into the enemy narrative of the foreign invaders going house-to-house and rooting through your underwear and chasing your kids around the backyard. That just helps the enemy’s recruitment.

Do you therefore think that, given enough time, the Iraqi forces will get it together? I ask because sometimes people argue that it’ll never happen and that Iraq isn’t a “real” country because it was designed by the West after World War I.

Well, that has some validity. What we call Iraq today was cobbled together under the British Mandate after World War I. Winston Churchill had a say in that, the archaeologist Gertrude Bell had a say in that … the Ottomans had always ruled Iraq as three separate segments: a Kurdish area up north, a Sunni Arab area sort of west and center, and then a Shia Arab area to the south. So there is some validity to that [argument]. That said, it sort of underscores the idea of an Iraqi solution. The Iraqi solution may be to partition the country; they may say there’s Shia Iraq and there’s Sunni Iraq (which is where ISIS is active) and there’s Kurdish Iraq, and that may be how they set it up. I think we have to be amenable to that because it’s got to be their solution …

The primary U.S. interest, at least as far as I can see, is making sure that whoever the bad actors are over there cannot threaten the U.S. homeland. Beyond that, there’s things we can do, but we must prevent the threat to the homeland.

Tell me about your idea for a commission about the wars along the lines of what was assembled to look into the security failures of 9/11. Why do you think this is something lawmakers should seriously consider?

I would think that since this war has been going on, in different fashions, since Sept. 11 of 2001 … We did a very thorough look at the Sept. 11 attacks … but we stopped there. This war now, we’re past our 13th year, and there need to be hearings, whether they are under the auspices of Congress or a blue-ribbon panel or a bipartisan committee. We need to hear from not just guys like me but from the diplomatic people and the intel people.

And it needs to be something that’s open to the public. It can’t be behind a green door where we all talk in code and nothing comes out. I thought [the 9/11 Commission] was a pretty good compromise. They certainly took some secret testimony, but there was a publicly released report that at least gave their best estimate of what happened, why it happened, and how to fix it. That’s what we really need to get after here.

It doesn’t feel like we’ve necessarily had that kind of reckoning when it comes to the 9/11 wars. Do you worry that failing to really understand the lessons of the last 13 years makes it more likely that we could repeat the same mistakes in the future — with Iran, for example?

I’m quite concerned about it. I didn’t serve in Vietnam, but all the guys who taught me when I came in in the ’70s all served in Vietnam and they all taught me that [what we did after 9/11] is what not to do. There’s things we learned that are positive, but for the majority [of cases] you don’t want to fight this kind of war. And yet, even though I’d heard from them and studied in the Staff College, the War College and all those other places I went, we still went into Iraq and Afghanistan and did it again. It worries me to an extent that, because of the quality of our all-volunteer force, we have a tendency to be a little arrogant and overestimate our own capabilities. That does worry me, if we were to take on another country, that we don’t think it out.

I hear people say things like, “If we had to deal with the Iranian nuclear program, it would strictly be an air campaign.” Well, maybe from the U.S. point of view it would be, but the Iranians get a vote in that, too. They may decide that the right thing to do if we do that is to strike out in a terror campaign that goes worldwide; they may cross the border into Afghanistan to mess with our people that are still there; they could cross the border into Iraq and head for the embassy there. They’ll choose their own course of action. We don’t know what it is, but it sure as hell probably won’t be what we want. We need to look before we leap and we’d better think it through thoroughly.

That’s why I really think we need this thorough look at what we learned from the war. To get it documented and, moreover, to share it with the American people so that everybody at least gets the information out in the open. My sense is that most people I’ve talked to since I’ve come home from Afghanistan aren’t happy with the way the war has gone, but they don’t know much about it. They sort of say, “Well, the military is handling that” — or the CIA or the government or whoever. They know it’s screwed up but then they don’t know much about it. I think it’s about time they do know something about it.