Minorities, Generation Gaps, and Future Elections

The 2012 election clearly validated the importance of minorities on the national political stage. But it also was an extremely polarizing election, with the Republican candidate gaining nine of his 10 votes from whites and the Democratic candidate capturing eight of every 10 minority votes. In addition to their potential for increasing racial divisions, future elections such as this one will not be demographically sustainable. If Mitt Romney could have eked out a victory, perhaps with greater white voter turnout, it would probably have been the “last hurrah” for a party strategy that relied primarily on whites as its base. Yet Obama’s win, which required super-sized minority outreach and turnout efforts while losing historically large numbers of white votes, is not a viable long-term strategy either. The projected rise in the minority portion of the electorate—from more than 30 percent in 2016 to nearly 40 percent in 2028—demands that both parties cross the racial divide to succeed in the future. Hispanics will contribute the most to this gain as they overtake blacks among eligible voters in 2020—two decades after Hispanics overtook blacks in the total population.

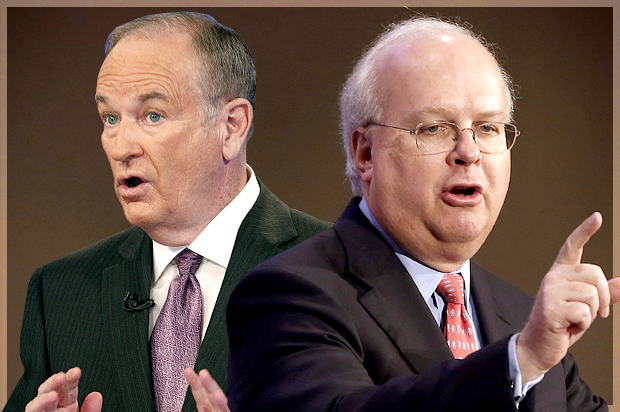

Potential crossover voting blocs also are on the horizon. Republican strategists such as Karl Rove, who engineered George W. Bush’s relatively strong showing among Hispanics in 2004, have long advocated for greater GOP outreach to minorities, Hispanics in particular. Although not completely successful in his efforts, Bush supported initiatives that would appeal to Hispanic voters, like education and immigration reform. Such initiatives received far less emphasis in the subsequent unsuccessful presidential bids of Republicans John McCain and Mitt Romney, but they are likely to be revisited as the GOP attempts to expand its reach to minorities. They may find some openings. The 2012 General Social Survey indicates that for both blacks and Hispanics, those under age 30 were more likely than their elders to call themselves independents and less likely to identify as Democrats.

Democrats, for their part, have continued to eye potentially winnable segments of the white electorate. In their 2002 book “The Emerging Democratic Majority,” John B. Judis and Ruy Teixeira show that although the Democrats have lost their advantage with the white working class, their focus on progressive issues is increasing the party’s appeal to rising white demographic segments in a post-industrial economy—professionals and women who, along with minorities, could reinvigorate the party’s base. More recently, political writer Ronald Brownstein coined the term “coalition of the ascendant” to identify key growing voting blocs that Democrats could cultivate to their advantage. These include minorities, white college graduates— particularly women—and the younger millennial generation. Although minorities are clearly a cornerstone of the party’s future, Brownstein points out that white college graduates are demographically significant. Among voters, they are becoming as numerous as traditional blue-collar whites and, especially among women, could become a solid Democratic constituency.

The millennial generation, in its overlap with the previous two blocs, could hold the most long-term promise. As young adults in both the 2008 and 2012 election, millennials propelled the strong 18- to 29-year-old vote for Obama. They are the most minority-dominant generation, and Pew Research Center polls show them to be more socially tolerant, liberal, open to larger government, and inclined to vote Democratic. If this generation, born between 1982 and 2003, continues to hold fast to those attitudes as they advance into middle age, Democrats would benefit greatly. Yet not all generations have held onto their youthful visions, as evidenced by many early baby boomers, who shifted politically to the right as they aged. The challenge for Democrats will be to retain the loyalties of millennials over the long term.

Given these trends, the country could be on the cusp of an emerging generation gap in voting patterns and in politics more broadly. The browning of America, starting with the younger generations, has caused a cultural generation gap between the young and the old. That became evident in past debates over immigration reform and in the competition for government resources between the young and the aged, as the largely white older generation feels disconnected from the increasingly diverse younger population. These kinds of divisions will emerge in national politics and in future presidential elections. Although the new racial shifts introduced by the millennial generation may very well drive current and future Democratic vote advantages, the national electorate will also include a large and growing senior population as the baby boom population continues to age.

The importance of the youth and minority voting blocs for Democrats is evident from the 2012 Democratic voting margins by age. Among all voters, it was the more youthful 18- to 29-year-old segment that gave Obama his greatest advantage, and within this age group, minorities clearly were the biggest contributors. Although young whites voted slightly against Obama (unlike in 2008, when they supported him), they showed the lowest Republican margins of all age groups among whites.

What these results also show is that older voters, especially older whites, favored the Republican candidate, Mitt Romney, most heavily. It is within older age groups that Republican-leaning, blue-collar whites who do not hold college degrees are prominent. These older age groups include members of the baby boom generation and the earlier “silent generation.” A Pew Research Center survey shows that in recent elections both of these cohorts favored Republican candidates, expressed reservations about the changing face of America, and generally wanted a smaller government with fewer services—with the exception of Social Security, for which they favor Democratic more than Republican approaches. More important, from a demographic standpoint, is the fact that these older generations of whites will continue to have staying power in the electorate.

There will clearly be a browning of the 18- to 29-year-old and 30- to 44-year-old segments of the electorate as the large millennial generation begins entering middle age in 2024. By then, minorities will constitute nearly one-half of young adult eligible voters and 40 percent of those ages 30 to 44. They represent voting blocs that are ripe for Democratic retention if current race and generational political affinities continue. During the same period, the large, mainly white group of voters age 45 to 64 will lose some of its white baby boom population as the latter advances into a sharply rising senior population. Votes from these two older groups will be easier for the Republican Party to retain if current generational voting affinities continue. Even if these trends do continue, there will still be a contest. That is, in 2024, the eligible voter population age 45 and above will be 26 percent larger than the population of eligible voters under age 45—a disparity that will be further widened by the higher turnout of older eligible voters.

Of course, today’s racial and generational proclivities are not necessarily destined to continue in a straight-line fashion. Democrats could make greater strides with key white voting blocs, including white college graduates—both men and women—who will increasingly dominate post-boomer generations of white voters. Republicans could make gains among Hispanics and other minorities. Furthermore, both parties will do their best to garner the favor of the growing, high-turnout senior population, which will be increasingly composed of baby boomers. In fact, the greatest challenge for both parties will be to meet the often conflicting needs of voters on both sides of the emerging cultural generation gap while still keeping the country on sound fiscal ground. To do so, they will have to persuade seniors that the key needs among striving young minorities—education, affordable housing, and steady employment—will work to benefit the Social Security and medical care programs that seniors will need in retirement.

Race and the nation’s battleground states

It might seem safe to assume that the popular vote scenario presented for future presidential elections will easily translate into actual election outcomes. But because presidents are elected on the basis of state-specific Electoral College votes, those outcomes could be muddied by state geography. The 2000 presidential election, in which Democrat Al Gore won the national popular vote but George W. Bush won the Electoral College vote, is a recent reminder that the two kinds of votes can differ. This is especially important to consider as the nation’s racial makeup shifts across regions and states. In particular, the New Sun Belt region is becoming part of an enlarged battleground of states as minorities become increasingly represented there.

The dispersal of the overall minority population is also occurring—with a lag—in the eligible voter population. Examine the racial makeup of eligible voters by state at the time of the 2012 election. Clearly, minorities are a sizable presence in many states, including those that are not in traditional coastal settlement areas. Minorities constitute nearly one-half or more of the electorate in Hawaii, New Mexico, California, Texas, and Washington, D.C., and at least one-third or more in a swath of additional states in the South and interior West.

Hispanics account for a substantial and increasing portion of the electorate in many western states as well as in Texas, Florida, New Jersey, New York, and Connecticut; in the latter states, they may soon approach blacks in electoral clout. Minorities constitute more than one-quarter of the electorate in most southern states, where blacks are the largest group (Florida, Texas, and Oklahoma excepted). Blacks still dominate the small minority populations in whiter Heartland states such as Michigan, Ohio, and Pennsylvania, although their much smaller Hispanic populations are rising, as in other parts of that region. Therefore, although the nation’s electorate is still divided somewhat between whiter Heartland states and heavily minority coastal states, states in the New Sun Belt stand at the forefront of electorate change. These include fast-growing western interior states that are receiving Hispanics and other minorities and prosperous southern states that are attracting blacks along with Hispanics from other regions.

This trend is illustrated in the minority contributions to the growth in eligible voters between the 2004 and 2012 elections in selected fast-growing states. In Arizona, Nevada, and Georgia, minorities contributed more than four-fifths to the growth of those states’ electorates, with Hispanics accounting for more than one-half in the first two states and blacks accounting for more than one-half in Georgia. Minorities contributed more than two-thirds to the increase in the eligible voter population in Texas and Florida and about one-half to the increase in Virginia. In contrast, Colorado and North Carolina, two other quickly growing New Sun Belt states, exhibited substantial white growth—although minorities still accounted for about one-third of the new eligible voters.

Minorities and Battleground State Expansion

The geographic dispersion of new minorities and the southward migration of blacks work to the advantage of the Democrats by enlarging the number of battleground states and allowing Democrats to cut into electoral turf that Republicans held steadily over a long period. In the 2004 election, as in the election four years earlier, George W. Bush won by making a nearly clean sweep of the interior West and South, along with Great Plains and several northern states—most notably Ohio—which were then dubbed battleground states. This Sun Belt sweep was not new to Republicans. Although they lost some Sun Belt states when southerner Bill Clinton ran in the three-way elections of 1992 and 1996 and when southerner Jimmy Carter ran in 1976 and 1980, the Republicans have held fairly firm control of the South since the civil rights years, when white southerners started voting in large numbers for Republican candidates. With very few exceptions, the mostly white conservative-leaning interior West states voted for Republicans continuously from 1968 to 2004, aside from the three-way elections of the 1990s.

The Democratic strongholds for the two elections prior to 2008 consisted of urbanized, racially diverse coastal states such as California and New York and a swath of states in New England, the Northeast, and the Midwest with industrial or farming histories. Although these states’ constituencies reflected both the new and the old strengths of the party—minorities, union workers, progressive professionals, and women—they did not represent the most rapidly growing parts of the country. This geographic map changed with both the 2008 and 2012 elections due to the changing racial demographics of a number of New Sun Belt states. In contrast to the Democratic performance in 2004, Obama won the new South and West battleground states of Nevada, New Mexico, Colorado, Virginia, Florida, and, in 2008, North Carolina.

The impact of demographic changes along with the new enthusiasm for Obama is illustrated in Nevada. In 2004, Nevada’s voters were 80 percent white, 8 percent Hispanic, 6 percent black, and 6 percent Asian or another race. Nevada’s white share dropped to 73 percent in 2008 and to 67 percent in 2012, when the Hispanic share rose to 15 percent, the black share to 9 percent, and the share of Asians or another race also to 9 percent. Aside from demographics alone, the Democratic voting margins increased, especially for Hispanics—from 21 in 2004 to 54 in 2008 and 47 in 2012.

Shifts in this direction were evident in most of the other Sun Belt states that Obama won in 2008, where a rise in the minority Democratic vote overcame the Republican white vote. For most of these South and West battleground states (North Carolina was the exception), Obama’s minority support was strong enough to overcome an increased white Republican margin in 2012. That was especially crucial in Florida, where the white Republican margin increased from 14 to 24 between 2008 and 2012. But due to a larger minority turnout and increased Democratic margins, Obama won this key battleground state again.

Minorities were responsible for winning five South and West battleground states in both 2008 and 2012, defeating the white Republican advantage for those states. That means that the growth of Hispanics and other new minorities and the southward migration of blacks were opening the door to greater future Democratic prospects in the Sun Belt—perhaps including previous Republican bastions such as Texas, Georgia, and Arizona, whose U.S.–born populations under age 18 are dominated by minorities. The Democrats’ short-term challenge in Georgia and Texas, particularly, will be to narrow the typically high white Republican voting margins, which have continued to offset gains in the size of the Democratic-leaning minority populations. This dynamic cannot last forever, as Texas is projected to have a minority-majority electorate as soon as the 2020 presidential election.

Reprinted with permission from “Diversity Explosion: How New Racial Demographics are Remaking America” by William H. Frey (Brookings Press, 2014).