"I don't know if any of you have heard of a magazine called the New Republic," said then-Treasury Secretary Donald Regan to an assembled group of reporters in early 1985, but, as he soon made clear, this hallowed home of historic heartbleeders, this perfidious parlor of pointyheaded pinkos, this effete embankment of Eastern Establishment elitism, had just "endorsed" Ronald Reagan's tax reform plan. What a victory for common sense.

Of course Regan, the no-nonsense former Merrill Lynch CEO, did not bother with the rhetorical flourishes attributed above. But the thrust of his comments was clear. It was a thrust that the Reagan administration and its allies found extremely useful during the 1980s whenever they needed to demonstrate just how silly and sectarian their adversaries were being. "My god," opponents of the nuclear freeze, proponents of the MX, boosters of the Contra war, critics of the civil rights movement, etc., could now say, "Even the liberal New Republic understands this issue well enough to see we're right. What can possibly be the matter with my distinguished opponent?" Michael Kinsley, editor for much of the period, once suggested that the magazine change its name to "Even the liberal New Republic..."

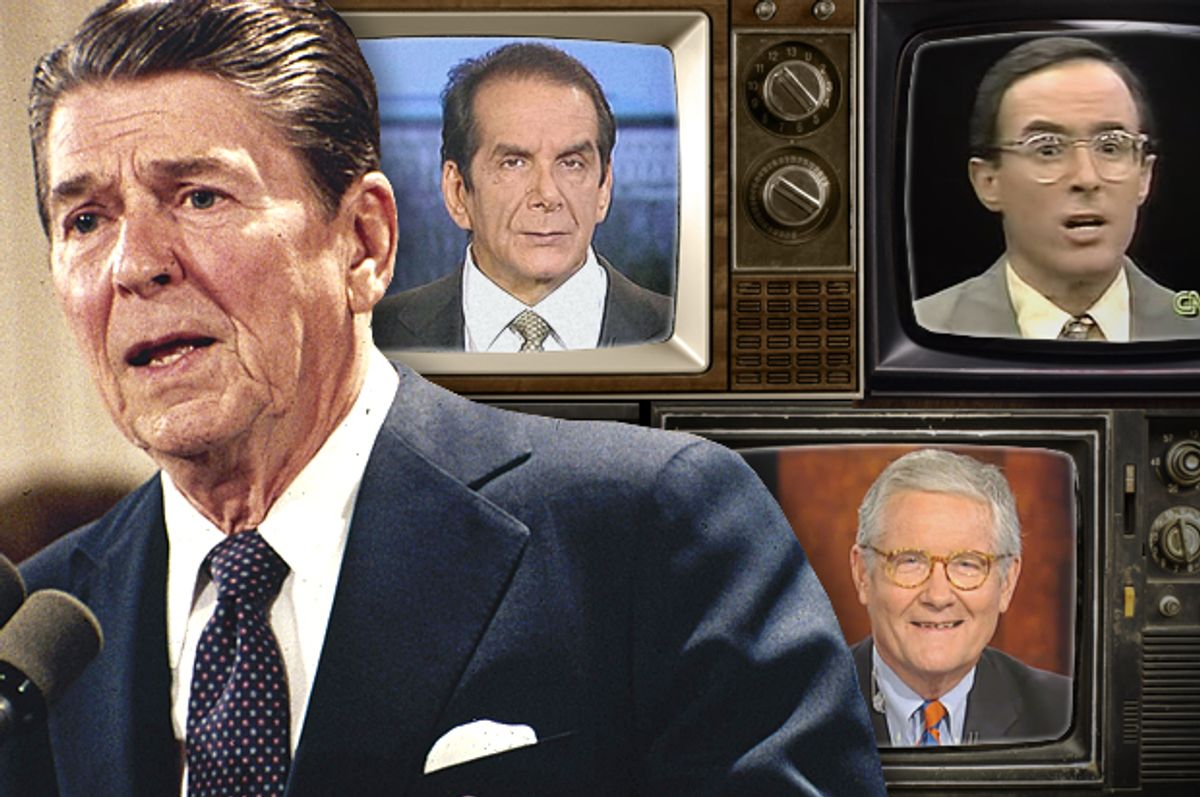

The degree of cultural hegemony exercised by TNR over right-thinking Washington insiders during the 1980s was difficult to explain outside the purview of its tiny empire. The ubiquitous presence of Michael Kinsley, Charles Krauthammer, Morton Kondracke, Fred Barnes and Leon Wieseltier throughout the opinion business adds up to considerable collective influence. The overall effect was even greater than the sum of its parts. Tastemaker Vanity Fair instructed its readers on two separate occasions between 1985 and 1988 that no fashion-conscious politico could aspire to hipness without "the smartest, most impudent weekly in the country" and the "most entertaining and intellectually agile magazine in the country." A New York Times cultural critic observed that the magazine's influence, as the 1990s began, seem "to be at, or certainly near, a new height." Right-wingers, in particular, could not get enough of this liberal magazine. Norman Podhoretz called it "indispensable." George Will referred to it as "currently the nation's most interesting and most important political journal." Buckley's National Review thought it "one of the most interesting magazines in the United States." The White House had twenty copies messengered every Thursday afternoon, minutes after the magazine returned from the printer.

As the above statements testify, the New Republic was, during the 1980s, the single most important repository of ideas and political ideology in the entire insider constellation. Excluding the nonpartisan National Journal, TNR was the only regularly read Washington-based magazine in which ideas and policy problems could be fleshed out to a degree that remotely reflected their contextual complexity, allowing for possible objections and meeting them with fully reasoned responses. Moreover, in a town where the standards of literary eloquence are embodied by General Accounting Office reports with titles like: "Administrative Systems: NASA Should Reassess its Automated Information Management (AIM) Program and Rescind its IBM-Compatible Policy" [May, 1990], the damn thing was actually fun to read. TNR was well written, perfectly attuned to the rhythms and genuflections of the insider dialogue, and extraordinarily--oftentimes diabolically--clever. Even those offended by its know-it-all tone or rightward political leanings could not help but admire its zippy writing style and engaging humor.

TNR's victory as the heavyweight champion of pundit-powered publications was partially a reflection of the state of its competition. Other magazines published important articles, but their influence rested largely upon the reputations of their authors. The only weekly periodical with comparable cache to that of TNR was the London Economist. While American journalists read The Economist with a degree of reverence that borders on worship, no magazine written and published across the Atlantic could seriously expect to be an decisive influence in the opinion-shaping game in Washington. The insider dialogue responds to stimuli so capricious and arcane that no one who is not fully immersed in it can expect to master it in a meaningful way for other insiders. Former TNR editor Mickey Kaus once lamented the difficulty of attempting to keep track of the insider dialogue from Los Angeles. "By the time you've heard Pat Caddell is touting Bruce Springsteen for president," Kaus bemoaned, "he has already switched to Dwight Gooden."

To the degree that TNR had any competition in the big idea business, it derived not so much from other publications as from television's two "quality" television interview programs, "Nightline" and "The MacNeil-Lehrer Newshour." In terms of pure star-making ability within the punditocracy, "Nightline" host Ted Koppel fell just percentage points behind God. Since the program surreptitiously hatched itself amidst the media chicanery surrounding the Iran Hostage Crisis of 1979, Koppel and company managed to forge a truly unique combination of highbrow respect and network financial support. To be interrupted in a meeting by a call from "Nightline" became the ultimate insider status symbol. To be invited on the show was akin to winning the lottery. Best of all was to be asked on to discuss a subject in which one had no particular expertise, which meant that Koppel had anointed you as a all-purpose wise man. During the '80s, New Republic editors Michael Kinsley, Hendrik Hertzberg, Charles Krauthammer and Leon Wieseltier all enjoyed this honor repeatedly. But "Nightline" did not set out to shape intellectual fashions so much as it mirrored them. For that reason, it suffered from many of the same defects that plague most objective journalism. Most of its invited experts were either public officials or former public officials. In an era dominated by conservative administrations, their minions enjoyed a considerable "Nightline" advantage. Moreover, since many of the Reagan administration's battles were fought between its incumbent "pragmatists" and "ideologues," the Left/Right split that television producers customarily sought for their guest spots usually featured a "liberal" supporter of the Reagan administration along with a representative of a position so extreme that not even Ronald Reagan could sign off on it.

The New Republic occasionally divided along these lines as well. Despite all evidence during this period, Morton Kondracke continued to insist that he was not a conservative, and so in the magazine's syndicated radio program, he would set himself up as the "liberal" in order to support Reaganite foreign policies. As late as August 1991, extreme conservatives like James J. Kilpatrick were still touting Kondracke's "liberal" bona-fides in celebration of his endorsement of their views. Were this the sum total effect of the magazine's efforts to undermine liberalism in the 1980s, it could be considered merely a pale, unimportant version of "The McLaughlin Group." But the magazine's assault on liberals and liberalism was far more interesting--and confusing--than that seen anywhere else in the punditocracy.

* * *

Somehow, during the 1980s, the New Republic managed to carry on its masthead a least a half dozen of the most interesting and original liberal writers in America, while at the same time providing conservatives with their most potent political/ideological weapons in the punditocracy's war of ideas. TNR argued the Reagan administration's case with far greater sophistication and nuance than did the administration itself. Moreover, by publishing hardline Reaganite views alongside those of its traditional liberal writers and insisting that both formed part of a single project designed to rejuvenate liberalism, the magazine succeeded in giving the fundamental precepts of Reaganite foreign policy--the military buildup, the proxy wars, the contemptuous unilateralism--what former editor-in-chief Hendrik Hertzberg called an important dose of "intellectual cache." Proponents of old-fashioned liberal values--non-intervention, multilateralism, social justice, and redistribution of wealth--were left with nowhere to go but The Nation, which, for most practical purposes, was considered so politically extreme that most insiders were afraid to pick one up without lead-lined gloves.

The act of retaining a liberal readership while publishing a flagship conservative publication was by definition a delicate one. The magazine's answer to its ideological conundrum was to seek refuge in a psychological term that previously had been taken to indicate a severe psychological disorder. Owner and president Martin Peretz bragged that "some people say we are schizophrenic, yet these are times when even the most thoughtful people are ambivalent."

In addition to "schizophrenia," the magazine's editors had great success in renegotiating the political connotation of the word "unpredictable." This term, for which Roget's Thesaurus offers "capricious, careless, immature, irresponsible, undependable and untrustworthy" as imperfect synonyms, became during the reign of the TNR the certifying adjective: the word that admitted formerly boring liberals into the exclusive club of the politically relevant and culturally chic. To be "predictable"--that is, to remain consistent to some definable set of principles or world view became, in the TNR lexicon, akin to cowardice, lilly-livered nostalgia, soft-headness and stilted mental growth. The Nation was predictable. Feminists were predictable. Civil rights leaders were predictable. But "the one sure thing," promised Peretz, "about this unpredictable magazine is that we will go on being unpredictable."

The unpredictable/schizophrenia strategy simultaneously won the magazine the new, influential audience it sought without driving away too many of the liberals who formed the backbone of its readership. It was also extremely helpful to the magazine's ability to secure corporate advertising. Freed from what its then-publisher Jeffrey Dearth called the "philosophical albatross" of the "dead-weight of knee-jerk liberalism," TNR was able to woo new corporate advertisers to its pages. More to point, however, was its ability to sway the insider dialogue. Just how, through the personality of its writers and editors, the magazine arrived at its `iconoclastic' definition of modern liberalism was a subject of endless speculation on the insider cocktail circuit in Washington. Everyone read the magazine, liberals angrily and conservatives with ill-concealed glee. Feminists, though put off by its Harvard frat-boy atmosphere--Henry Fairlie once compared it to an ancient Greek gymnasium--nevertheless appreciated its pro-feminist politics. Radicals on both sides of the political divide agreed that the only Washington seemed to find the magazine's arguments so fascinating was the fact that its conservatives insisted upon calling themselves liberals. As Nation columnist Christopher Hitchens complained:

The preface to this was always to be able to say, "Look, I've been a liberal all my life, it is in my roots, my fingertips and my hair, and it is in that capacity that I say I like the contras, or I like the MX, or what's so wrong with Ivan Boesky?" These are statements which would be perfectly trite on their own--they almost would have some distance to go before reaching trite--but because of the `I'm a liberal' preface, they are invested with a kind of daring and appear brave.

Right-wing writer Dinesh D'Souza concurred:

Articles triumphantly circulated on the Right would probably be ho-hum items if they appeared in National Review or the American Spectator... Perhaps TNR's only new idea is that its old ideas aren't very good.... But if TNR articles give credibility to the right, perhaps the magazine considers this a small price to pay for getting itself taken seriously by conservatives--who happen to be in power.

However unimpressed were critics like these, the benefits of calling oneself liberal while endorsing Reaganite goals were manifestly apparent at the magazine's November 1984 70th anniversary party. There among the silk cummerbunds and caviar blinis, editors heard themselves praised by such liberal luminaries as Patrick Buchanan, Jeane Kirkpatrick, Irving Kristol and Henry Kissinger. Dr. K (to whom, in 1977, the magazine had bid farewell with an editorial entitled "Good Riddance,") complained with a straight face that the evening had been "traumatic" for him. "I have been photographed with so many liberals, my semiannual visits to the White House will now be even less frequent."

* * *

One of the enduring mysteries about TNR's role in the political and cultural wars of the 1980s was the fact that, while its liberals were considered by far more talented and interesting than its conservatives, it was the latter whose political views defined its stature within the punditocracy. This was even stranger given the fact that for much of the period, its editor in chief was the writer widely recognized as the most talented liberal pundit in more than a generation.

To say that former editor-in-chief, Michael Kinsley, has led a charmed life is to commit oneself to considerable understatement. Compared to Kinsley, Dobie Gillis grew up in downtown Baluchistan. Loving parents, suburban Detroit childhood, private schools, Harvard, Rhodes scholarship, Harvard Law School, five summers working for Ralph Nader, one summer as managing editor of the neoliberal Washington Monthly, and finally at the ripe old age of 25 (and still in law school) managing editor of TNR. With a weird kind of glamourous nebbishness that frequently put him on top of Washington's most eligible bachelors lists, Kinsley somehow lived up to all the myths that New Republicans tried to create about themselves. He was ideologically anti-ideological. He had an unerring eye for cant, hypocrisy and sanctimony. He was hysterically funny and perhaps most important, politically fearless.

Kinsley turned sacred cows into hamburger without regard to political or ideological affinity. During the '80s he has scorched the earth on targets ranging from Jonathan Schell's high-minded nuclear apocalysm, to his own magazine's infatuation with anti-Communist guerrillas, welfare programs for the wealthy, and the unfairness of the Social Security tax. His column on the latter issue inspired Daniel Patrick Moynihan to introduce a bill cutting the tax, thereby throwing the Democratic Party into yet another unsolved identify crisis and forcing the entire Congress to calculate the size of the deficit slightly less dishonestly. His satires on the self-important stupidity of such Washington pundits as Hugh Sidey and the cast of "Agronsky and Company" show were funnier and more biting than anything in this book.

But however talented as writer or critic he may be, Kinsley does not inspire. He laughs, he cajoles, he mocks, and he satirizes, but even the most astute reader of his work would have a hard time conjuring up what motivates Kinsley's political zeal. Kinsley credits neoliberal guru and Washington Monthly editor Charlie Peters with inspiring his personal philosophy, but after two decades of neoliberal proselytizing, its fundamentals still appear decidedly fuzzy. Kinsley is against overtaxing poor people and subsidizing wealthy ones. He is an ardent free-trader, and believes that capitalism would benefit from a collapse in real estate prices. He seems to admire Ralph Nader, his former employer, whom he sees as "operating on the mental fringe where self-abnegation blurs into self obsession." But Kinsley himself is obsessed by nothing. He dedicates himself simply to delineating the foibles of contemporary Washington life. Kinsleyism might fairly be called Dukakisism with a sense of humor. However satisfying it may be for upper-middle-class yuppies, this is not the foundation of a resurgent liberalism.

Whenever Kinsley got fed up with taking orders from Peretz, he would resign as the magazine's editor and be replaced by Hendrik Hertzberg. Kinsley had no competition as the most talented liberal pundit in Washington, but if he had, it would have been Hertzberg. Emanating from a less ambivalently bleeding heart, Hertzberg's politics derived from exactly the emotionally driven sense of commitment that was lacking in Kinsley. A one-time New Yorker editor and Carter speechwriter, Hertzberg was a traditional social democrat who wrote with a keen eye, an engaging sense of humor, and a wonderful feel for unintended irony. Here is Hendrik Hertzberg on the 1988 Iowa primary:

The big Democratic winner, of course, was Richard Gephardt, a man who puts me in mind, unreasonably to be sure, of an earthling whose body has been taken over by space aliens. I keep expecting him to reach under his chin and peel back that immobile, monochromatic, oddly smooth face to reveal the lizard beneath. Perhaps the aliens are from the planet Bryan. How else to explain the fact that Gephardt, who until a few months ago was sort of a neoconservative, neoliberal, has suddenly begun talking, in his slow robotic voice, like a devotee of Populism?

Rounding out the liberal stable at the magazine during the 1980s were Sidney Blumenthal and Leon Wieseltier. Blumenthal, who spent much of the decade at the Washington Post, nevertheless contributed to TNR a powerful ability to mine the underlying cultural elements of American politics and a deep devotion to the presidential candidacy of Bill Clinton. (He would later work directly for the president.) Wieseltier, a brilliant medieval Jewish scholar whom Peretz plucked from the elevated vines of Harvard's Society of Fellows, was an extremely ambivalent liberal, who tended to arrive at conventional liberal political positions via almost Hegelian-style intellectual complications.

If the four writers discussed above were given free rein to write and publish TNR, supplemented by thoughtful liberal contributing editors such as Ronald Steel, Robert Reich, and Robert Kuttner, TNR would most likely would have been exactly the challenging liberal publication that American politics so sorely lacked in the 1980s. Such a magazine would have been decidedly less radical than the Nation, but better able to integrate moral, political, and social questions into a policy framework. Such a magazine would also have been at the cutting edge of Democratic party politics, helping the more progressive elements of the debate fashion a coherent response to the breakdown of the social contract that for years ensured the primacy of the New Deal coalition. But, then of course, no one would have had occasion to beat down his liberal opponents by insisting that "even The New Republic" understood the necessity of whatever Reaganite measure happened to be on the table.

* * *

When Martin Peretz took over The New Republic, both had reached their respective political and philosophical dead ends. Peretz had attended Brandeis before becoming a left-wing (graduate) student activist at Harvard. A dedicated Zionist with many millions of dollars at his disposal, he had given up trying to overthrow the system and was now ready to work within it. Peretz and the New Left parted company when black revolutionaries began to condemn Israel as a racist and imperialist outpost. He felt a deep devotion to the Jewish state, explaining to Henry Kissinger during the 1967 Arab/Israeli war, that his "dovishness stopped at the delicatessen door."

Peretz and his second wife, Anne Labouisse Farnsworth, had funded some of the decade's most ambitious political efforts along with some of its most disastrous ones. Peretz had invested himself wholeheartedly in both the arguments and the personal style of the movement, and its collapse left him at loose ends. One freshman at Harvard in 1966, James Fallows, who says he was "straight off the boat" from the Goldwaterite conservatism of his Southern California upbringing, applied to join a seminar Peretz was conducting on the Vietnam War. Fallows recalls feeling Peretz's "withering contempt" for someone who, like this California rube, was not "sufficiently or stylishly anti-American in his view of the war." But by the early '70s, with Peretz's academic career stymied and his politics moving on a rightward arc, however, the couple was looking for new political investments.

The New Republic, meanwhile, had drifted into a kind of courtly irrelevance. Its post-Lippmann zenith had taken place more than a decade earlier when the handsome young president emerged from Air Force One ready to lead the Free World, holding a copy of that week's issue beneath his arm. But ideological ferment of the 1960s, coupled with the failure of liberalism's wars--on the Vietnamese in Indochina and on poverty in America's cities--had left its most venerable institutions exhausted and confused; TNR was no exception.

The Peretzes purchased the magazine from owner/editor Gilbert Harrison in 1974, with the understanding that Harrison would remain editor for three years. That arrangement lasted 10 months. One day Harrison entered the stately 19th street townhouse to find his Queen Anne desk and John Marin paintings in the hallway and Martin Peretz sitting in what had until the day before been Harrison's office. The New Republic's era of "unpredictability" had begun.

In the beginning, there were the words. Upon taking over the magazine, Peretz would frequently subject the holdover staff to profane verbal abuse before firing them, says Philip Terzian, an editor whom Peretz fired, and whose recollections may be colored by his unmitigated hatred for the man. Harrison's staff feared Peretz to turn TNR into a liberal version of Commentary, with all issues decided on the basis of what was "good for the Jews." Peretz went so far in this direction, says Terzian, that he instructed his editors to pick up material from the Israeli embassy that he would later run as TNR editorials. "It was a very wild place," recalled Henry Fairlie, who remained close to Peretz until his death in 1990, "run by a sort of Jewish cowboy with an open shirt."

Peretz originally told the Washington Post that he planned to "toughen The New Republic's liberalism with more aggressive, sharply argued opinions now being exploited by conservatives." But the most obvious manner in which these positions were sharpened and toughened up was by heaving them overboard. The political retooling of the magazine began immediately but proceeded fitfully during the Ford and Carter eras, and not always according to political principle. This confused readers and writers alike. Speaking of a book review commissioned more than a dozen years earlier, Peretz recalled to the literary critic Alfred Kazin in 1989 that, "the worst thing I ever did to you was when I suppressed your [negative] review of [the Stalinist author] Lillian Hellman. She scared me shitless."

While Peretz allowed Kinsley and his cohorts a generally free hand with much of the magazine's domestic agenda, he gradually reshaped its foreign policy to reflect the contours of the emerging counter-establishment realignment. Michael Ledeen, a shadowy, failed academic accused of perjury by his colleagues, and a man with still-murky ties to the Italian Secret Service, began to appear prominently in the magazine. Kenneth Adelman, Reagan's future anti-arms control adviser, also saw his Right-wing polemics featured frequently. Other invited Neocons included Jeane Kirkpatrick, Edward Luttwak, and the ubiquitous Irving Kristol. The only point of contact between the old liberals and the New Rightists was a consistently pro-Israel hard line.

Unlike Norman Podhoretz's monochromatic Commentary, Peretz's neoconservative leanings stretched him in many directions simultaneously. First came the most conventional: Peretz hired Morton Kondracke from the Chicago Sun-Times, and the reporter quickly converted from liberal to neoconservative in tune with the tenor of the late Carter era. When Kondracke left on his brief Newsweek sojourn, he was replaced by the even more conservative Fred Barnes. When Kondracke returned, Barnes remained. Both men made their livings by professing faith in the conventional wisdom of the moment. Neither one proved an intellectual match for the magazine's liberals but each had qualities that endeared him to insiderdom.

The charitable explanation for Morton Kondracke was simply that he was a likable fellow who had fallen in with the wrong crowd. Kondracke worked hard, but suffered from a built-in homing device for conventional insider thinking regardless of the issue. Without trying or perhaps even being aware of it, Kondracke speaks, as Kinsley has noted, with the voice of "official" Washington. As one TNR editor put it, "Central America is wherever Mort is."

Fred Barnes, a born-again Christian, was less a member of the close-knit Peretz mishpacha than Kondracke, but excelled as the kind of inside pooper-scooper who kept TNR on the punditocracy's cutting edge. White House sources knew his to be a sympathetic ear and thus went to great efforts to fill it early and often. They would leak to him on Tuesday to make his TNR deadline and then again on Friday morning for "The McLaughlin Group."

Barnes and Kondracke kept the magazine current, but it was Charles Krauthammer who undertook a five-year mission to shape its liberal philosophy and boldly take it where no liberal had gone before. Almost alone among TNR's Neocon stable, Krauthammer brought both arguments and an intelligence that were taken seriously by its liberal half. As Kinsley put it, "Before I know my argument is sound, I like to run it hypothetically through Charles."

Krauthammer had been chief resident of Psychiatric Consultation Services at Massachusetts General Hospital before coming to Washington with one of his professors in 1978. After a stint as Walter Mondale's speechwriter, he joined TNR as a senior editor, later expanding his portfolio to op-ed pages, newsweeklies, and pundit sitcoms. As with most neocons, Krauthammer was never willing to give up his insistence that he was the real liberal. Hendrik Hertzberg, whose job it was to argue with him, calls Krauthammer a "left-wing Nneocon on domestic matters and a hard-right neocon on foreign policy." This is in contrast to Peretz, who, according to Hertzberg, had been a "left-wing neocon" both foreign and domestically, during the '80s. These distinctions are important. For as Kondracke reveals, while both he and Krauthammer began as "disciples of Peretz at the outset, increasingly Peretz and I became inspired by Krauthammer."

During the Krauthammer ascendancy, TNR editorials took a progressively harder line, and developed a frequent habit of questioning the motives of its opponents. The sentiments underlying these editorials often recalled a different McCarthy than the one to whom Peretz had helped bankroll in 1968. Those who did not see things the magazine's way became "second-rate thinkers," "self-indulgent, solipsistic," "Sandinista sympathizers," "fellow-travellers and their ilk." One editorial accused "Democrats, including some in Congress," of "positively identifying with the Sandinistas, their social designs, their political ends and even their hostility to the United States." This tactic infuriated Wieseltier, who explains:

Charles' great contribution to the debate was to question to motives of his opponents. One of the great neoconservative habits--[Norman] Podhoretz has perfected it--was that since your own view is obviously correct, anyone who disagrees with you must suffer from a human frailty. The explanation cannot be intellectual, it must be psychological. Because if the intellectual differences were granted, that would imply there was something to argue about. But there is nothing to argue about. So it is obvious that there must be something the matter with that person, and so you look to his ambitions, his motives, his wife. Something.

The questioning of liberal motives during the Reagan years was part of a frontal assault by the magazine upon the chastened, post-Vietnam internationalism that characterized the Democratic party's mainstream. At the beginning of the Reagan administration, when its opponents coalesced behind a proposal for a mutual, verifiable freeze on the production and development of nuclear weapons, the magazine attacked both the proposal and its partisans. When the conference of Catholic bishops proclaimed nuclear deterrence to be immoral, TNR wrote that "there are few greater sins against sanity that the weakening of deterrence. Like the president, the bishops have sinned." "Utopian thinking has always offered lofty rationalization for risk, for tampering with the foundations," explained TNR's editors in yet another editorial that equated the willingness to negotiate a reduction in arms with the Soviets with "utopianism" and "risk," but "this time the risk is too great, the foundations too shaky."

Opposing the peace movement and arms control caucuses within the Democratic party, the magazine threw its considerable persuasive powers being behind the construction of two new ICBMs, the ten-warheaded MX, and the single warheaded midgetman. In 1983, when the Reagan administration engineered the "Scowcroft Report"--a propaganda document conceived by one of the decade's many bipartisan commissions of conservative Democrats and Republicans to build support for otherwise unsupportable Reagan administration policies--TNR wrote, "The Commission has accomplished nothing less than a revolution in doctrine." What this revolution constituted in political terms, however, was merely the agreement of the administration to build midgetman missiles in addition to its beloved MX. TNR professed to detest the MX, observing at one point that "only if we wish to start a nuclear war--do we need the MX." But it was willing to endorse its development as a means to persuade the Reagan administration to build a fleet of midgetmen missiles as well. The "revolution," however, never arrived. The Reagan administration got its MXes, to be sure, with crucial New Republican Democrats supporting it. But none of the administration's promises with regard to the Scowcroft Commission report were ever fulfilled.

Although it was passionate in support of the continuance of the nuclear arms race, the magazine reserved much of its most vociferous rhetorical support for the administration's proxy wars in Central America. With regard to El Salvador, the magazine's editors managed to convince themselves that by 1986, "the military and police, which rightist thugs once dominated, are slowly but meaningfully becoming more professional and apolitical." El Salvador, wrote the editors," is a democracy in the process of becoming, and it is therefore a big credit on Ronald Reagan's ledger--and also on the ledger of moderate Democrats who weren't afraid to cross the partisan line." If fact, El Salvador, in 1986, was still a hellish country, run by exactly those thuggish elements TNR sought to whitewash. According to figures assembled by the human rights office of the Catholic Archdiocese in San Salvador, in the period between 1980 to 1989, government sponsored-or assisted death squads killed 41,048 citizens. The equivalent figure for the left-wing guerillas, including kidnappings, was 776. When in November 1989, these same U.S.-equipped and trained, "professional and apolitical" soldiers chose among their grisly victims six Jesuit priests, their cook and her daughter, and then following their murders, conspired to cover up their responsibility and protect the guilty parties, the magazine (with the exception of Kondracke) began to backpedal. With between 50,000 and 70,000 lives and nearly $6 billion wasted in the endless Salvadoran civil war, the country made a mockery of the magazine's 1986 insistence that "what has happened there should cheer all who welcome the strengthening of the democratic center in Central America."

While TNR fought hard to win support for the Reagan administration's policies in El Salvador, its heart belonged to the contras. For TNR's Neocons, the Nicaragua of the 1980s was not a country but an existential opportunity. In the overblown rhetoric used by contra supporters during the various battles, one could hear echoes of Seville, Saigon and Munich. Nicaragua was where good and evil were facing off for what promised to be a final showdown: The "Communist totalitarians" vs. the "Democratic resistance."

It was through the invention of the Reagan Doctrine, with its ire focused on tiny Nicaragua, that Krauthammer and The New Republic demonstrated decisively how central punditry had become in the formation of the insider consensus that ruled American policy in the 1980s. The idea steamrolled through all three rings of the punditocracy, aided considerably by Kraut hammer's unmediated access to each of them. The advantage of having a "doctrine" to defend their their lies and dissimulations was considerable to William Casey, Oliver North, Elliott Abrams and their allies in the bureaucracy. They could sell it to private contributors, manipulate it in confidential white papers, and seize on it as a justification for trading arms for hostages, diverting the money to their friends, and lying about it Congress and the American people. Details about this or that massacre or drug-smuggling operation could be swept under the rug on behalf of the exalted moral calling the "doctrine" invoked. Everyone likes to think he is toiling on behalf of some greater idea larger than themselves--larger even, than the country for whose interests they labor. Krauthammer's creation not only flattered these people, it inspired them; some so much they were later indicted by a Washington grand jury.

But more than a mere higher calling was involved. Washington public relations firms--the people who are paid good money to understand these things, however subliminally--knew a milk cow when they saw one. They flew the Reagan Doctrine flag and lobbied administration officials to include their well-paying anti-Communist clients on the list of U.S.-funded Reagan Doctrine "freedom fighters." Rival public relations firms adopted Marxist regimes as their clients in order to fight them. Thus, Reagan's closest friend, Robert Gray, head of the powerhouse Gray and Company, adopted the cause of the Marxist government of Angola, only to give it up when young Reaganites picketed his stately Georgetown offices. Soon, the South African creation in Mozambique--RENAMO--and the noncommunist guerrillas in Cambodia attached themselves to the Reagan Doctrine teat, basking in all the pro-freedom and democracy rhetoric that passionate supporters of the Afghans and contras were generating. Right-wing adventurer Jack Wheeler revealed something of the value of Krauthammer's service to the cause when he told Sidney Blumenthal, then of the Post, that "we had him [Krauthammer] in for an off-the-record lunch with the president. He popularized the term, a rallying point for conservatives.... I love that guy Krauthammer for inventing the `Reagan Doctrine.'"

While the Reagan Doctrine knew no borders, the object of its most passionate affections was always Managua. When push came to shove on a crucial Congressional vote, virtually the entire edifice of the nation's foreign policy seemed to rest on these agrarian democrats. According to one Krauthammer-authored editorial, "the liberation of Angola, Afghanistan, and Cambodia would not have one-tenth the geopolitical importance--and psychological importance for other oppressed democrats--that the replacement of the Sandinista regime with a democratic government in Managua would." The upcoming vote somehow became "one of the most important foreign policy votes of the decade."

Charles Krauthammer's Nicaragua editorials are among the most significant documents of the entire era. They embraced all of the cliches of the Reaganite mind-set, with regard to both the "moral equivalent of our founding fathers" in Nicaragua and the functional equivalents of Neville Chamberlain at home. Krauthammer rested the contras' Jeffersonian bona fides upon the allegedly "impeccably democratic" shoulders of its civilian directorate, Arturo Cruz and former Coca-Cola magnate Adolfo Calero. He did so despite the fact that Robert Owen, the Right-Wing Congressional aide appointed by both Abrams and Oliver North to act as a go-between for the contras and the American government, was describing the civilians in a secret memo as "a creation of the USG to garner support from Congress." Those Americans who observed that the Soviets and Cubans were more than ready and willing to match our own military commitment in Nicaragua were smeared as "the council of pure defeatism." To those who noted the fact that Nicaragua's neighbors preferred a peaceful solution, Krauthammer and company insisted that these countries were merely reading the tea leaves of liberal cowardice. Seeing "an isolationist Congress and a rising military power in Managua," they fell into the grip of public appeasement and private duplicity. Secretly, TNR assured its readers (and apparently on the basis of mass mental telepathy), Nicaraguans were "desperate to see the United States get rid of the Sandinistas for them."

The editorial was, noted contra supporter Wieseltier, "the worst piece of agitprop writing I have read since I got here. It talked about the other side's motives, and it made the case in the administration's words, rather than in our own." Twelve TNR contributing editors apparently agreed, and banded together to sign a letter of protest that was summarily buried in the magazine's back pages. Kinsley ripped the editorial to pieces in his own column calling the logic it employed, "preposterous," "fatuous," and a "logical contortion." Hendrik Hertzberg did not critique the piece in public, but believes that sentiments such as these finally led him to resign as editor of the magazine. "The magazine was playing a role," he explained, "where I just couldn't be the front man for it anymore."

What Hertzberg had in mind here was not merely the Krauthammer/Peretz powers of persuasion evinced in the magazine's editorials, but also the efforts of a group of formerly liberal political operatives to use it. Saluted in the pages of the magazine as "a handful of young Democratic intellectuals and activists, Robert Leiken, Bernard Aronson, Bruce Cameron and Penn Kemble [who] will have been found... when the history of the American debates over Nicaragua is written... to have transformed both public discussions and public policy," these apostate liberals worked closely with Abrams and Oliver North to try to sway the swing votes in Congress. Their vehicle of choice was The New Republic. As Sidney Blumenthal observes, these "pro-contra operatives were able to use the pages of TNR to develop a public strategy to complement a political strategy that they were working on inside Congress. This gave legitimacy to the whole effort." It also helped Aronson earn Elliott Abrams' old job in the Bush administration. Not a bad day's work for a magazine whose editors lectured poor Salman Rushdie that "it is the place of the writer and the intellectual to be outside, not inside; not to be a part of, but to be not a part of."

Because the endless contra debate in Congress focused on the votes of fewer than two dozen swing Democrats in the House of Representatives, these interventions would prove absolutely crucial in convincing Congress to approve military aid. Pat Buchanan was calling the Democrats "the party of Communism" at the time, and Norman Podhoretz insisted that "in a conflict where the only choice is between Communists and anti-Communists, anyone who refuses to help the anti-Communists is helping the Communists." The Democrats could not allow themselves to be perceived to be responding to threats quite this vulgar, but they were looking for cover from them nevertheless. The most influential of these swing votes, House Armed Services Committee Chair Les Aspin, and Coalition for a Democratic Majority Member Dave McCurdy, were particularly susceptible to the compliments heaped upon them by the editors of TNR, who noted the willingness on the part of these "moderate Democrats who weren't afraid to cross party lines" and who were willing to "lead and to take risks." Aspin even hired Leiken, briefly, as an informal adviser and paid his way to Nicaragua to survey the situation. Together, they prevailed upon the key swing Democrats to back contra aid and allow the war to continue at crucial moments in the debate. This pattern repeated itself for two years, until Oliver North and Robert McFarlane put an end to it with a bible and a birthday cake in Tehran.

When the contra cause crumbled, Krauthammer and company only heated up their rhetoric even further, employing language that turned out to be wholly inaccurate but that should have sent a shudder down the spine of those dedicated to free public debate. Borrowing a page from Podhoretz, Krauthammer compared contra/Sandinista cease-fire accords to "the similar speedy peace" that "Congress brought Indochina in 1975." Going back even further in the history of stab-in-the-back politics, he also promised that "who lost Central America will become an issue some day and on that question it is worth keeping the record straight and the memory fresh." Democratic Speaker Jim Wright, had, in Krauthammer's evocative words, "made Central America safe for Communism."

Aside from the violence it inflicted upon the English language, the most significant damage inflicted by the Neoconservative view of Latin America was the inexplicable importance it placed on pathetic little Nicaragua to the exclusion of the rest of the region. The magazine's friend and confidant, Assistant Secretary of State for Inter-American Affairs and admitted liar, Elliott Abrams, said he spent almost half his time on this one tortured nation. In the meantime, staggering economic debt in Latin America, coupled with extremely fragile democratic development and environmentally unsustainable investment patterns across the continent, were undermining the long-term viability of the truly strategic nations of the region. In Argentina, by the end of the decade, inflation reached 3,700, percent while the government accumulated an unpayable debt of $65 billion. Brazil, another nation of enormous strategic importance, saw its inflation rate rise to 1,765 percent in 1989, with an accompanying debt of $100 billion. Closer to home, Mexico, a nation of millions of potential economic refugees, saw its debt shoot up to $107 billion in 1987 with a relatively modest inflation rate of 160 percent. The Andean nation of Peru, a supplier of much of the U.S. cocaine market, experienced an inflation rate of 2,275 percent and a ten percent drop in growth in 1989 alone. Bolivia, another cocaine producing nation, may have set the all time world's record with an annual inflation rate of 8,170 percent in 1985. Environmental destruction in these places also approached crisis proportions. In Peru, farmers were even razing sections of the Amazon rain forest to sow coca crops for export to America's cities. All of these countries are unarguably more important to the future economic and political security of the United States than either Nicaragua or El Salvador. Yet, owing in part to the punditocracy's Reagan Doctrine-inspired obsession with these two countries--including, particularly, arguments calling this or that contra vote "one of the most important foreign policy votes of the decade"--not one them attracted a fraction of the attention necessary to fashion a coherent American response.

*

It is impossible to write about TNR without coming to grips with Peretz and Israel. It is not enough to say that TNR's then-owner is merely obsessed with Israel; he says so himself. But more importantly, Peretz is obsessed with Israel's critics, Israel's would-be critics, and people who never heard of Israel, but might one day know someone who might someday become a critic. "Israel, lion of nations, loyal ally and democratic outpost, Israel, gateway of Meccas, is of course, a land of religious resonance and geopolitical significance," wrote James Wolcott trying to describe Peretz's mindset on the subject. He understated the case considerably.

One could, if one were sufficiently conspiratorially minded, draw a political TNR map of the world based wholly on the Israel connection. The Sandinistas were bad because they accepted PLO advisers. The UN was useless because it invited Yassir Arafat to speak. Jesse Jackson was dangerous because he sang "We Shall Overcome" with West Bank Palestinians and spoke up for their right to statehood. The Salvadoran government was deserving of U.S. military support because it accepted Israeli military trainers and voted with the Israelis in the UN. Bill Moyers was a fraud because he once spoke up for the right of Arab-Americans to criticize Israel in the media.

Of course TNR's flight into the arms of the Right was based on political and psychological factors far more complex than just Israel, but the notion retains a kind of subliminal credibility. Since he gave up on revolution, Peretz has devoted himself to fighting for Israel on all fronts, a crusade not uncommon among Neocons. Influential intellectuals of both the Right and Left in Western Europe hold the rather oversimplified and unsophisticated view that the entire rightward drift of American liberalism during the sixties and seventies can be viewed as a result of the change in Israel's geopolitical status from the spirited socialist David of its early years to the pro-American empire, post-1967 military Goliath. (The Six-Day War was important to the birth of neoconservatism, but so were the New York city teachers' strike and the blatantly anti-Semitic rhetoric of much of black America's most vocal leadership.) Still, there are uncountable ironies involved in TNR's treatment of Israel's critics--not least of which is the fact that, while few people are so frequently reviled in TNR's editorials as those who openly call for the establishment of a Palestinian state living in peace alongside Israel, no fewer than four of the magazine's editors--Kinsley, Hertzberg, Blumenthal, and Wieseltier all say they would support the establishment of such a [demilitarized] state. Wieseltier, a one-time member of the Jewish Defense League and every bit as devoted a Zionist as Peretz, says he would give his right arm to see it tomorrow.

TNR's role in the Arab/Israeli debate is both simple and complicated. Norman Podhoretz has argued that "the role of Jews who write in both the Jewish and general press is to defend Israel." Critical reporting of Israel, Podhoretz insists, "helps Israel's enemies--and they are legion in the U.S.--to say more and more openly that Israel is not a democratic country." Peretz has never advocated anything quite this explicit, but one could argue, not wholly inaccurately, that his primary task as editor and owner of TNR has been to praise Israel and subvert those he deems to be her opponents.

Marty Peretz does not like Arabs. They have, he argues, "a national characterological inability to compromise" and tend toward the "violent," "fratricidal," "unreliable," "primitive," and "crazed." Even worse, however, are Palestinian Arabs. TNR editorials often treat the word "Palestinian" as a synonym for "terrorist." In an interview with the Israeli newspaper Ha'aretz during the 1982 Israeli invasion of Lebanon, Peretz explained that the Israelis should administer to the PLO: "a lasting military defeat that will clarify to the Palestinians living in the West Bank that their struggle for an independent state has suffered a setback of many years. [Then the] Palestinians will be turned into just another crushed nation, like the Kurds or the Afghans...[The problem] is beginning to be boring." When asked what he objected to most about the magazine he edited, Michael Kinsley responded, "I have a problem with some of the needlessly vicious things about Arabs that we publish."

Another significant responsibility Peretz has undertaken on behalf of Israel's interests has been the ideological policing of the American media. Peretz calls U.S. media coverage of the Middle East "an obsessive wound in my heart." If so, he has managed to offer this pain considerable balm in the editorial pages of his magazine. This wound accounts for what one TNR editor calls "Marty's ridiculous obsession with [New York Times columnist] Tony Lewis." It also seems to account for the magazine's sahmeful vilification of I.F. Stone over a period of decades. During the 1982 Israeli siege of Beirut, during which Israel turned off all water and electricity services to the Moslem sections of the city, Peretz spotted Stone's name on an appeal for "the victims including hundreds of thousands trapped in West Beirut without water, essential services and medical supplies." Peretz singled out Stone, a devoted friend of Israel's peace camp, from the list of signatories and accused him of caring "only" for those "trapped in West Beirut," whom he insisted were trapped not by the surrounding Israeli army but by the PLO. "So this is what I.F. Stone has come to," wrote Peretz, "asking his admirers to put up money so that the PLO can continue to fight, not simply against Israel but against the possibility of a peaceful Lebanon." "I do think sometimes we attack people unfairly" admits Wieseltier.

Peretz's most ambitious media enforcement operation of the '80s came during the Israeli invasion when he authored a cover story entitled "Lebanon Eyewitness." After being treated to a brief tour of the war zone by Israeli military intelligence, Peretz assured his readers that the news reports they had read and television coverage they had seen were simply false. He would single out for particular opproprium, The Washington Post and ABC News. One cannot hope to judge how journalists fudged their stories, or did not report them at all, in order to avoid being singled out for treatment like this. "We're the cops" on Israel explains one TNR editor. "Marty really put the fear of the devil into the media after Lebanon." With more than $4 billion in aid monies riding on perceptions of Israel in Congress each year, the importance of this kind of police work can hardly be overestimated.

But Peretz is only half the story. Leon Wieseltier is correct when he says "There is no question that on Israel we have had it a million ways. Yes, our rhetorical heat has been out front, but we have published some of the most anti-Israeli policy stuff anywhere." TNR has published a cover with a map of the Middle East featuring a Palestinian state on it. Wieseltier, Irving Howe and Michael Walzer have all written articles extremely critical of the policies of the Israeli government. During the '80s, the magazine called on Begin to resign and made an enemy of Yitzhak Shamir. It has published Robert Kuttner's attack upon the "unholy alliance" between Jewish PACs and far-Right politicians on the cover as well. In a seminal issue published during the height of the intifada in March 1988, Wieseltier endorsed many of the PLO's demands for a mini-state alongside that of Israel. Even Peretz declared "the policy of occupation and settlement" to be "in ruins." It fell to Krauthammer to defend the hawkish ground that TNR had historically occupied, arguing that to cede any territory to the current generation of Palestinian leadership would constitute "surrender" to "rioting."

TNR's dovish pieces on the Middle East, particularly those by Wieseltier, have been tremendously important within the American Jewish community in legitimizing the kind of dissent from the Israeli party line that Peretz and Krauthammer have made a career of attacking. On the one hand, this is a confusing phenomenon. Why would Peretz--whose attacks on the likes of Stone, Lewis, Edward Said and others associated with criticism of Israel or support for Palestinian rights are almost unparalleled in their bile and venom content--allow his magazine to be used to publicize similar positions in the mouths of others? Part of the answer lies the magazine's celebration of political diversity, which in the matter of Israel, extends beyond the parameters of its American agenda. Perhaps more significant, however, is the fact that support for a Palestinian state or criticism of Israel's occupation is not the point. The point is who is doing the criticizing. Those whom Peretz determines to be criticizing Israel out of genuine concern for her best interests are generally left alone. Those whose primary concern appears to be the conditions of Palestinian life are savaged within an inch of their professional reputations.

*

One question liberals asked constantly during the '80s was why, if a primary function of TNR's liberal editors-in-chief was to make the magazine's neoconservatism more palatable, did they stick around for the party? The answers, like everything at TNR, are complicated. Kinsley says that his decision to edit a magazine whose political thrust he did not support was, in essence, "a Faustian bargain." The bargain amounted to the fact that he could publish whatever he wanted:

The price was I had to publish things I didn't want. I thought that was a pretty good arrangement. It comes out every week. There is a lot of crap in it, but if I have anything I want said or want to say, I can say it in a national magazine without having to pay the bills. Yes, the war in Nicaragua bothered me as did our endorsement of it, but I was considerably soothed by being able to publish the opposite view, and it seems to me that anybody reading both would think that I was right.

Hertzberg's refusal to adopt Kinsley's stratagem (that is to publish a liberal magazine within a conservative one), led to frequent "Fuck you, Ricks" and "Fuck you, Martys" shouted in the hallways of the magazine during the early '80s, with Hertzberg telling one reporter that Peretz was "oafish and bullying." "The initial way I dealt with the tension," recalls Hertzberg, "was to resign... I became sufficiently disturbed with the role of TNR and the general thrust of the role that I was playing in the Reagan years that I left. I didn't feel alienated to the point that I wasn't perfectly happy to write for the magazine but I didn't want to be a front man for it any longer."

In addition to the contras, Hertzberg was angered by the public role played by TNR in undermining the nuclear freeze movement and supporting the MX. "I wanted our position to be one of critical support rather than critical opposition. Instead, the magazine showed contempt for its arms control thinking and questioned the backgrounds of many of the movement's leaders." It does not bother Hertzberg that the magazine subjects civil rights or social-policy organizers to fine-tooth scrutiny. "What the magazine should be criticized for," he allows, "is for not subjecting power to the same kind of criticism."

Beginning in late 1986, the magazine began to draw itself away from Reagan and Reaganism and concentrate a bit more of its fire on "power." The magazine's October 13, 1986 editorial on "The Reagan Hangover," was among the first frontal attacks on the legacy of Ronald Reagan in the mainstream media and among the only ones that proceeded the revelations of the Iran-Contra scandal. But during the 1988 election, TNR's editors, like much of the punditocracy, focused on the wholly irrelevant question of which Democratic candidate would likely be toughest on the Russians. They attacked Dukakis for his willingness to "parrot the left isolationist line," his "standard issue McGovernite left worldview" and his refusal to endorse the TNR theology on the nuclear freeze, the MX, and most particularly, the Reagan doctrine. The magazine chose as its favored candidate former Peretz student and midgetman booster Albert Gore of Tennessee. Gore ran a perfectly conceived Neocon campaign, talking tough to the surrendering Gorbachev, and prostrating himself before the Shamir government to curry favor with New York's Jews. Advised extensively by Peretz and Wieseltier, his campaign fizzled in New York where even the Jews found his hawkishness a bit too kosher for comfort. With its anemic 10 percent of the total Democratic vote, the Gore campaign in the end proved to a kind of metaphor for just how far The New Republic had drifted from the concerns of the sophisticated Democratic voters for whom the magazine's editors had, for the previous decade, pretended to speak.

THE NEW REPUBLIC IN THE '90s

The Weekly Standard took Fred Barnes and Charles Krauthammer away from TNR just as Michael Kinsley, Hendrick Hertzberg, Jacob Weisberg, Sidney Blumenthal and others also severed their relationship with the magazine. The result was a much weaker publication that spent the 1990s enduring one professional humilation after another. First one of its star young writers, Ruth Shalit, was accused of a string of plagiaries. Next, its high-profile gay-Catholic-Tory-editor, Andrew Sullivan, "was resigned." Sullivan was deemed by some staff members to care more about posing for GAP ads than editing the actual magazine. The changes he did bring to the magazine were almost uniformly awful. He put a young man named Stephen Glass in charge of fact-checking, who turned out to be a serial plagiarist. He featured Charles Murray’s racist pseudo-science on the cover and encouraged essays by Camille Paglia in which she wrote of “Hillary the man-woman and bitch goddess.” Michael Lewis wrote a piece in 1994 about the “weird degradation” of being married to a beautiful part-time model, Kate Bohner. One conservative writer compared the magazine under Sullivan to “watching a middle-aged accountant try on a pair of nipple rings.”

Not much improved under Michael Kelly, whom Peretz chose to replace Sullivan. In the press release announcing his hiring, Peretz compared him to Thucydides. Alas it would be difficult to find a less apt role model in all human history. Under Kelly, twenty-five-year-old Stephen Glass continued to publish fiction as reporting, while his editor attacked the integrity of those who raised questions about his work. To one critic, Kelly wrote, “You lied because lying supported your thesis, and you attempted to cover up your lie. You have shown that you are willing to smear someone’s professional reputation without any concern for truth…. I await your apology to Stephen Glass and to this magazine.” It turned out that 27 of his 41 stories contained considerable fabrications.

But Glass was the least of TNR’s problems under Kelly. For it turned out that in Michael Kelly, Martin Peretz had managed to hire an editor for America’s most venerable liberal magazine who happened to hate liberals. In his inaugural “TRB” column, written shortly after the 1996 election that liberalism had become an “ideology of self-styled saints; a philosophy of determined perversity. Its animating impulse is to marginalize itself and then to enjoy its own company. And to make it as unattractive to as many as possible; if it were a person, it would pierce its tongue.” Kelly shared Peretz’s animus toward affirmative action and consistently attack the nation’s civil rights establishment, in much the same way that Peretz would beat up the Palestinians. Black people seemed to be causing trouble nearly every where you turned, according to TNR’s coverage under Kelly. And the beating that Kelly gave Clinton was so relentless and so obsessive, that Peretz could no longer stand it—particularly when he was so heavily invested in Al Gore’s Y2K candidacy What’s more the old delicate balance of having a smart liberal edit a neoconservative magazine was destroyed. TNR was a liberal magazine at the end of Kelly’s reign only in memory.

When Peretz finally pushed Kelly over the side, he was replaced by longtime contributor Charles Lane, who quieted down the clamor, firing Glass and allowing Shalit to take her leave. But in letting go of liberalism and destroying its reputation for high-quality journalism, the magazine succeeded only in making itself invisible. True, Leon Wieseltier’s literary pages remained the best anywhere in America, but politically, speaking, the magazine ceased to matter. The magazine’s best conservative writers had gone off to form the nucleus of Rupert Murdoch’s Weekly Standard. The liberals had gone either to The New Yorker, with Hertzberg, or with Kinsley to Slate. The latter’s brilliant TRB columns and razor-sharp editing, and the former’s passionate prose were now part of an ever distant past. The flagship of American liberalism, at the end of the century, had lost its reason for being.

Excerpted from "Sound & Fury: The Washington Punditocracy and the Collapse of American Politics" by Eric Alterman. Reprinted with permission of the author. All rights reserved.

Shares