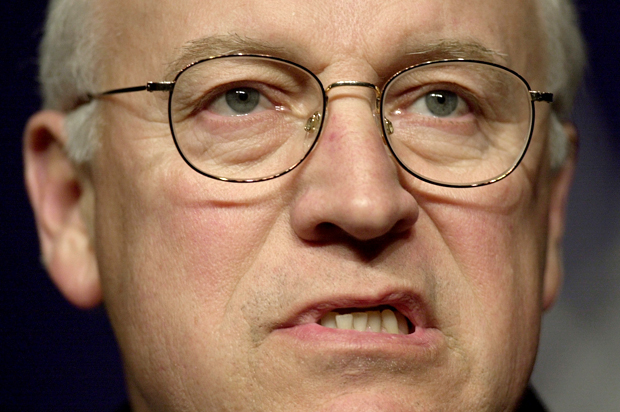

As many of us wade through the horror of the Senate torture report, it’s hard not to think back to a time when the man who ran the country explained to us in plain language what he was doing. I’m talking about Vice President Dick Cheney, of course, the official who smoothly seized the reins of power after 9/11 and guided national security policy throughout his eight years in office. He was one of the most adept bureaucratic players American politics has ever produced and it’s his doctrine, not the Bush Doctrine, that spurred government actions from the very beginning. It was called the One Percent Doctrine and according to author Ron Suskind it went like this:

If there’s a 1% chance that Pakistani scientists are helping al-Qaeda build or develop a nuclear weapon, we have to treat it as a certainty in terms of our response. It’s not about our analysis … It’s about our response.

Or put another way: “It’s time to take the gloves off.”

This was the philosophy that propelled the U.S. government to abandon any pretense of following the post-WWII international consensus about preventive war and inhumane tactics. Despite the fact that the U.S. had lived under a real existential nuclear threat for decades, they persuaded the people that this terrorist threat was so much greater that any rules and norms in place before 9/11 were no longer operative. If even a 1 percent chance existed that we might suffer an attack, we had to do whatever was in our capability, including torture, to stop it. That this also facilitated the long-term goals of Dick Cheney and other neocons was purely coincidence.

He used the One Percent Doctrine most effectively to con the nation into backing an inexplicable invasion of a nation that had nothing to do with the attacks on America. And he was able to rationalize it with many people who knew better by evoking his doctrine: if there was only a 1 percent chance that Saddam had nuclear weapons or a 1 percent chance that he was in league with al-Qaida, we had to react. And so we did. And that kind of thinking permeated the U.S. government, particularly the intelligence services. The analytical side was bullied into providing intelligence conclusions that weren’t based in fact. The covert agents simply went over to the dark side. The military wasn’t immune. The torture regimes of Guantánamo and the treatment of prisoners in Iraq are on them.

And let’s not forget the cowardice and abdication of duty among most elected officials of both parties and the media who were eager to believe whatever propaganda served the One Percent Doctrine. Yes, they were lied to. And the fact is that for the most part they were grateful for it. Even if there was only a 1 percent chance that something terrible could happen, the political risk was too great for them to speak out in anything but the most tepid terms. If they didn’t know the truth it was because they wanted it that way.

It must be acknowledged that members of the media were among the first to call for torture. And long before John Yoo developed his sociopathic view that anything short of causing pain “equal to that of organ failure” was not torture, highly respected legal scholars were openly calling for torture to be legalized, even offering up tips like using “sterilized needles under fingernails.” In fact, the idea to jettison the taboo on torture became part of the conversation after 9/11 almost instantaneously. So much so that it’s clear it was more a reflexive desire to punish than any need for intelligence. And that desire to punish was perhaps best articulated by the experienced cheerleader President Bush when he famously stood atop the rubble of the World Trade Center and said, “I can hear you! The rest of the world hears you! And the people — and the people who knocked these buildings down will hear all of us soon!”

But even though the excuses these days are all about how the chaos of the early days and the pain of the attacks led the government to “make mistakes,” that’s really no excuse. A thirst for revenge is human. Anger and anguish are natural responses to the horrors of 9/11. But we assume that our leaders are going to rise above those human emotions to deal with a crisis. That’s what you have leaders for. And, frankly, that’s what Dick Cheney did. While everyone else was running around in circles, Cheney was back in Washington taking advantage of the hysteria to do what he had set out to do back in the 1970s when he had served first in Nixon’s White House and then under Donald Rumsfeld in Gerald Ford’s administration after the ignominious departure of President Richard Nixon.

He had been appalled that Nixon’s overreach had resulted in an erosion of presidential power and repulsed by what he saw as a retreat from the world during the post-Vietnam years. He happened to have been the White House liaison on intelligence matters when the first round of CIA abuses was revealed and he learned that the agencies could ride them out. When his friend George Bush was tapped to run the CIA he knew there would be no further reprisals. Another lesson well learned. He and Rumsfeld engineered a number of internal bureaucratic coups resulting in one of the first neoconservative triumphs, the creation of Team B and an alternative intelligence analysis of the Soviet threat that showed that U.S. national security was in grave danger. He learned how useful such intelligence could be. It was widely discredited in later years but it succeeded in helping get Ronald Reagan elected and proved to be extremely helpful in restoring presidential national security prerogatives.

But even the Reagan years weren’t enough to appease him, what with what he saw as continued usurpation of the executive with congressional interference in foreign policy and silly scandals like Iran-Contra. The highlight of his time in government came as secretary of defense during the first Gulf War, a triumph of American imperial power. It was short-lived, of course, as President George Bush was drummed out of office and a Democrat took the helm. It was at that point that he and the neoconservative claque that had first formed around Team B became a fully formed rival government in exile and began to plot a return to Iraq to “finish the job.” He got his chance on September 11, 2001, with plans they had at the ready just waiting for a pretext.

But 9/11 opened a new door for Cheney as well. The One Percent Doctrine not only presented him with a perfect chance to restore presidential authority to its full power, he could enlist members of the opposing party, the press and a large number of the American people in his goal to exempt the U.S. military empire from all obligations to international law and norms. It was not considered a problem if America had to go it alone. In fact, in many ways it was preferable. (It’s the logic of Winner Take All Politics, writ large.) It was American Exceptionalism to the 10th power: No matter how infinitesimal the threat we may act, and act with brutal force. We’ve got your new world order for you, right here. By capitalizing on the fear and anger among Americans after 9/11, and even more important, leveraging the political cowardice of his opponents, Dick Cheney deftly manipulated an atmosphere of chaos to his desired ends: an imperial presidency, a permanent war footing and an even more powerful national security apparatus that operates with impunity.

As we all wring our hands and rend our garments over an official report that reveals what we already knew, the system he put in place remains intact and operating at full steam. The president washes his hands of the past, the Congress declares its innocence and then averts its eyes, the CIA says it was only following orders, and the press clutches its collective pearls unable to even use the word “torture” when questioning the head of the agency about horrors it perpetrated.

On Thursday, John Brennan, the head of the CIA, wouldn’t rule out using torture in the future. On Sunday, the program’s most energetic enthusiast, Cheney, went on national television and when asked by Chuck Todd whether the fact that 25% of the prisoners who were tortured were found to be innocent should have any bearing on the decision to do it, he replied:

I have no problem as long as we achieve our objective. And our objective is to get the guys who did 9/11 and it is to avoid another attack against the United States. I was prepared and we did. We got authorizing from the president and authorization from the Justice Department to go forward with the program. It worked. It worked now for 13 years.

We’ve avoided another mass casualty attack against the United States. And we did capture Bin Laden. We did capture an awful lot of the senior guys at Al Qaeda who were responsible for that attack on 9/11. I’d do it again in a minute.

Basically he put the whole world on notice that the world’s only superpower would use any means it chooses without limit or restriction to obtain its objectives.

Dick Cheney must be very proud of his life’s work this week. The brother of the unrepentant president who ordered torture is today considered the most serious Republican candidate for the White House and there can be no doubt that he would continue those practices. The opposition will do little more than make tepid complaints and, if history is any guide, even Democratic presidents of the future who object to such tactics will feel compelled to protect them after the fact.

He accomplished exactly what he set out to do all those decades ago. If a White House can get away with ordering torture and bragging about it, it can get away with anything. His cruel legacy is complete.