“There is no longer any doubt as to whether the current administration has committed war crimes. The only question that remains to be answered is whether those who ordered the use of torture will be held to account.”

— Maj. Gen. Antonio Taguba, June 2008

We’ve seen it in Ferguson, Missouri, with Darren Wilson getting off scot-free for killing Michael Brown. And we’ve seen it again in Staten Island, with Daniel Pantaleo getting off scot-free for killing Eric Garner. So why shouldn’t scores of CIA agents, contractors, higher-ups and other government officials—including former President Bush and Vice President Dick Cheney—get off scot-free for torturing hundreds of detainees, including some complete innocents? That, apparently, is the reigning logic following the release of the Senate torture report.

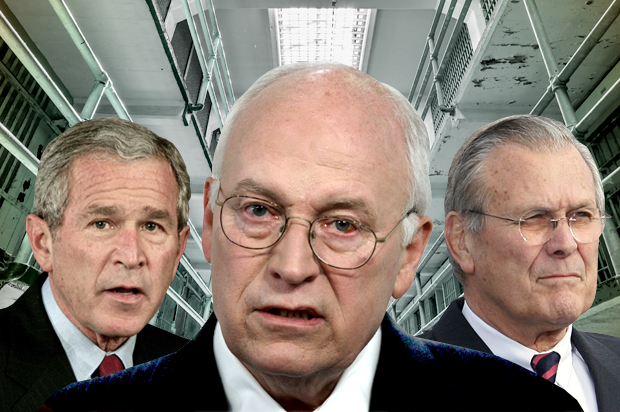

But just as genuine legal experts have been appalled by the perversion of normal and normative legal process in the grand jury proceedings in St. Louis County and Staten Island, there’s been a sharp line drawn by human rights lawyers and advocates in response to the Senate torture report, calling for prosecutions to match the crimes. A 2011 report from Human Rights Watch, “Getting Away With Torture: The Bush Administration and Mistreatment of Detainees,” argued, among other things, for the criminal prosecution of former President Bush, Vice President Cheney, Defense Secretary Rumsfeld and CIA Director George Tenet. Nothing has changed since then, HRW executive director Kenneth Roth told Salon.

“We believe in 2011 and we believe just as strongly today that senior U.S. leaders have a case to answer for torture and war crimes,” Roth said. Although the Senate report’s focus is narrower than that earlier report—ignoring the issue of renditions and everything done by military as well—where it does focus, it has only reinforced what HRW has been arguing.

“I would say the evidence becomes even stronger for [prosecuting] the CIA leadership, because it’s clear that they were turning a purposely blind eye even to reports of torture,” Roth continued. “The report talks a lot about how the CIA lied and covered up, but it doesn’t change the fact that the basic practices were authorized, you know, waterboarding, sleep deprivation, things like that.” But also, “George Bush approved waterboarding by his own admission, he approved the CIA renditions program,” while Cheney “was the driving force behind many of the illegal detention and interrogation policies to begin with.”

As for the legal obligations involved, “The torture convention requires that acts of torture be referred to the competent authority for the purpose of prosecution,” Roth said. “The United States has an obligation to prosecute torture.” Ben Emmerson, the U.N. special rapporteur on counter-terrorism and human rights, agreed. “The individuals responsible for the criminal conspiracy revealed in today’s report must be brought to justice, and must face criminal penalties commensurate with the gravity of their crimes,” he said.

Woven through such calls for the pursuit of justice, there’s a similar subtext: that the welter of information presented needs to be carefully and critically sifted through in the light of our highest values, as well as the principles of international law, which America has done so much to help create based on those same values.”What would it mean to be a nation committed to the rule of law, if we don’t hold people responsible for crimes of this magnitude?” ACLU deputy legal director Jameel Jaffer asked on MSNBC.

The need for such action is only made more urgent by the fact a new Pew poll shows 56 percent of Americans believe the lie that torture provided intelligence that helped prevent terrorist attacks, and relatedly that 51 percent think that “the CIA’s interrogation methods … were justified.”

As the Intercept’s Dan Froomkin tweeted, “If 56 percent of Americans think ‘CIA interrogation’ was effective, all that tells us is that they’ve been misled,” adding, “Just like 70 percent of Americans once though Saddam was behind 9/11, now 56 percent think torture worked. This is a massive indictment of the U.S. media.” But it’s not just the media. America’s entire elite infrastructure is indicted in this state of affairs, which is why America so desperately needs to have broad-based, high-profile torture trials on the model of the Nuremberg Trials following World War II—trials that will both hold those responsible accountable for what they’ve done, and force the whole nation to engage in a profound moral reorientation, on the order of what Martin Luther King Jr. once called for. This is not an easy path, to be sure, but it’s far easier than decade after decade of endless war in which America’s moral purpose becomes increasingly lost in the shadows of our own unconfronted fears.

Al-Qaida’s whole aim with the 9/11 attacks was to draw the U.S. into a self-destructive conflict in the Middle East, and to expose and exploit our contradictions. And thanks primarily to the Bush/Cheney delusional response (and Obama’s limited willingness to alter direction), that’s exactly what has happened. We did not narrowly focus on bringing those who attacked us to justice—we swiftly attacked Afghanistan, short-circuiting any chance of negotiating to swiftly put bin Laden and his associates on trial, we then let bin Laden escape, while becoming enmeshed in Afghan internal conflicts, after which Bush said he was “truly … not that concerned” about bin Laden. We then invaded Iraq—which had nothing to do with 9/11, and was profoundly hostile to al-Qaida—and set off a series of internal conflicts which eventuated in the creation of ISIL, which is far more dangerous and has far more international support than al-Qaida ever dreamed of.

In short, everything the U.S. has done since 9/11 has been seriously misguided at best, and Obama’s policy changes have merely trimmed around the edges of what Bush and Cheney started, because he has been obsessed with trying to quickly unify the country, papering over profound differences, rather than facing up to the genuine deep difficulties of overcoming them. We saw this, for example, when he released a set of torture memos in response to a lawsuit in April 2009, and said:

This is a time for reflection, not retribution. I respect the strong views and emotions that these issues evoke. We have been through a dark and painful chapter in our history. But at a time of great challenges and disturbing disunity, nothing will be gained by spending our time and energy laying blame for the past. Our national greatness is embedded in America’s ability to right its course in concert with our core values, and to move forward with confidence. That is why we must resist the forces that divide us, and instead come together on behalf of our common future.

Just how we were supposed to “move forward with confidence” without reexamining how we had gone wrong, Obama never bothered to explain. It would be hard enough were mere mistakes involved, but we’re talking about grave crimes that undermine the very idea of America—just as al-Qaida intended when it attacked us on 9/11.

Those mistakes cried out for correction, but instead Obama invoked the shameful, discredited Nazi Nuremberg Defense (“I was only following orders”), when he said:

In releasing these memos, it is our intention to assure those who carried out their duties relying in good faith upon legal advice from the Department of Justice that they will not be subject to prosecution.

Not only is this an insult to the real heroes, who spoke out against the barbarism they were tasked with, the Nuremberg Principles, which came out of the Nuremberg Trials, explicitly rejected this defense:

Principle IV

The fact that a person acted pursuant to order of his Government or of a superior does not relieve him from responsibility under international law, provided a moral choice was in fact possible to him.

They also rejected the notion that those who give the orders are exempt:

Principle III

The fact that a person who committed an act which constitutes a crime under international law acted as Head of State or responsible government official does not relieve him from responsibility under international law.

These two principles aren’t that hard to grasp, for anyone familiar with TV crime dramas. Both the hit man and the man who orders the hit are guilty of murder. Street crimes, suite crimes, international war crimes—the same logic applies equally to all of them.

As already noted, earlier reports have already made it clear that crimes were committed. The Senate report’s greatest value lies in the light it sheds on competing “theories of the crime”—explanatory accounts of what happened and why, which are also familiar from TV crime dramas, particularly ones like “Law and Order,” which got so much mileage out of shifting and competing theories of the crime, from the initial crime scene and eyewitness accounts to the final verdict and last comments made on it. A theory of the crime creates a context for understanding how all the different pieces fit together. It has to make sense in a how-things-work kind of way, what I’ve referred to before as the explanatory mode of “logos,” but it also serves to make sense by giving them meaning, the explanatory mode of “mythos.”

When 56 percent of Americans say they believe that torture provided intelligence that helped prevent terrorist attacks, they’re making a claim that torture worked—which says something both about the real-world, logos–type effects that were produced, as well as about the mythos–type nature of what those engaged in torture were doing. The need to believe in the mythos involved routinely trumps the logos side of the equation. And yet, on five key points where arguments have been prominently pushed , evidence in the torture report and elsewhere clearly contradicts theories of the crime that would let torturers off the hook—along with those who gave the orders. Evidence also suggests several neglected theories of the crime that provide a profoundly different view of what our recent history has been—and what our future could be, by way of contrast.

It Wasn’t About Getting Information

For example, the day before the Senate torture report was released, national security blogger/journalist/author Marcy Wheeler pointed out it’s a mistake to assume that getting information was the primary aim of torture, by which it should be judged. This wasn’t just her opinion—it was actually a matter of record:

As the Senate Armed Services Committee Report on torture (released over five years ago, in far less redacted form than tomorrow’s summary will be) makes clear, the Bush regime embraced torture not for “intelligence” but for “exploitation.” In December 2001, when DOD first started searching for what would become torture, it was explicitly looking for “exploitation.”

The term “exploitation” includes intelligence-gathering, but it also includes spy recruitment and propaganda—politically useful, often false information, such as “the case of Ibn Sheikh al-Libi, whose torture-induced claim al Qaeda had ties to Iraq’s WMD programs helped drag us into Iraq,” and “Abd al-Rahim al-Nashiri [who] claimed his torturers told him he had to claim Osama bin Laden had nukes, among others. When you consider all these cases, she writes:

Then it raises the really horrible possibility that Cheney pushed torture because it would produce the stories he wanted told. It would be difficult to distinguish whether Cheney believed this stuff and therefore that’s what the torture produced or whether Cheney wanted these stories told and that’s what the torture produced.

Difficult, indeed. But either way, it reminded me of what George Lakoff told me about the concept of “reflexivity”:

It has to do with the fact that thought is part of the world. That when you’re thinking, it’s not separate from reality, it’s part of reality. And if your understanding of the world is reflected in what you do, then that thought comes into the world through your actions. And then through your actions, if many people have the same ideas, those ideas are going to spread, and they’re going to come back and reinforce themselves, because they will change the world.

This adds another layer to the theory of the crime that Wheeler draws our attention to. Given that conservatives are much more sensitive to perceived threats in the world, it’s not surprising that reflexivity on their part creates a more dangerous world, even as they pound their chests and proclaim their superiority in dealing with the very dangers they create. We see the same process at work with the killers of Trayvon Martin, Michael Brown and Eric Garner—the mere presence of a black male sends them into a panic, even though they’re the ones who are actually armed and dangerous. This sort of irrational fear places their behavior outside the standard of reasonableness on which a justifiable homicide theory of the crime depends, and the same can be said about the entire Bush/Cheney response to 9/11, of which the torture program was just one part.

The lack of discipline, oversight, reliability and candor that permeated the torture program, as revealed in the Senate torture report, has been seen by some as proof that Bush, in particular, was not in charge, ergo not responsible. But all that flowed directly from Bush and Cheney’s unhinged response to 9/11—they were in control by being out of control, because they couldn’t be otherwise. And—like the killer cops referred to above—they actively resisted normal processes that would have curbed their dangerous, deadly excesses.

In a similar abnormal fashion, Bush even tried to get Congress to authorize going to war against Iraq without bothering to have the CIA do a national intelligence estimate, the traditional formal document used to integrate all the available intelligence data into a single comprehensive analysis. “An intelligence official says that’s because the White House doesn’t want to detail the uncertainties that persist about Iraq’s arsenal and Saddam’s intentions,” USA Today reported on Sept. 10, 2002.

In that same forgotten blockbuster of a story, USA Today reported that the decision to invade Iraq had been made within weeks of 9/11, but without any formal decision process:

The decision to target Saddam “kind of evolved, but it’s not clear and neat,” a senior administration official says, calling it “policymaking by osmosis.”

“There wasn’t a flash moment. There’s no decision meeting,” national security adviser Condoleezza Rice says. “But Iraq had been on the radar screen — that it was a danger and that it was something you were going to have to deal with eventually … before Sept. 11, because we knew that this was a problem.”

This same mind-set of panic-driven deliberate carelessness characterized the Bush administration approach to every major aspect of the war on terror, making it exceeding difficult to pin down responsibility for anything—which is precisely the point. And yet, their responsibility is clear: Through reflexivity, Bush and Cheney’s unhinged panic drove the entire process off the rails. Yet, even today they and their defenders continue to pretend that they were the tough guys, the realists, the ones who protected us. They need to stand trial in part simply so that this lie can be publicly put to rest. But the same goes for five points mentioned above, the five false theories of the crime, which need to be publicly replaced with their opposites.

The purpose of the sorts of trials we need is twofold: first, on the logos side, is to sort through competing theories of the crime, to which hold up and which do not, and to judge individuals accordingly. Second, on the mythos side, is to alter our collective understanding of the past, so that we can move forward having learned our lessons deeply, in ways that reshape us for the better forever. With that in mind, let’s consider each of the different theories of the crime in turn.

First Theory of the Crime: There was a crime. We tortured people.

The first theory of the crime in any case concerns whether one even occurred. Was something stolen, or lost? Was a person murdered, or did they commit suicide? Or die accidentally? In this case, were people tortured in violation of U.S. and international law? Many torture apologists say there was no crime, but there’s already an abundance of evidence to the contrary, even before the Senate torture report. The most significant evidence it provides on this score includes:

- New details about just how gruesome the treatment was. This is captured in a single summary paragraph from the committee’s finding No. 3 “The interrogations of CIA detainees were brutal and far worse than the CIA represented to policymakers and others”:

At least five CIA detainees were subjected to “rectal rehydration” or rectal feeding without documented medical necessity. The CIA placed detainees in ice water “baths.” The CIA led several detainees to believe they would never be allowed to leave CIA custody alive, suggesting to one detainee that he would only leave in a coffin-shaped box. One interrogator told another detainee that he would never go to court, because “we can never let the world know what I have done to you.” CIA officers also threatened at least three detainees with harm to their families—to include threats to harm the children of a detainee, threats to sexually abuse the mother of a detainee, and a threat to “cut [a detainee’s] mother’s throat.”

- Evidence that CIA management and lawyers were aware that U.S. law said one thing, and they were doing another. This began before they decided to break the law, but had recurring ripple effects afterward. In the early days after 9/11, CIA leadership clearly recognized the existence of legal limits, which would later be intentionally set aside [Ex Sum, p 12]:

On September 27, 2001, CIA Headquarters informed CIA Stations that any future CIA detention facility would have to meet “U.S. POW Standards.”

… In early November 2001, CIA Headquarters further determined that any future CIA detention facility would have to meet U.S. prison standards and that CIA detention and interrogation operations should be tailored to “meet the requirements of U.S. law and the federal rules of criminal procedure,” adding that “[s]pecific methods of interrogation w[ould] be permissible so long as they generally comport with commonly accepted practices deemed lawful by U.S. courts.

There are others examples of the second sort, including one cited by Business Insider here. But these two passages are sufficient, from a logos-based point of view, to establish probable cause that a crime was indeed committed—and not just a single crime, but a widespread deliberate pattern of them. Of course there will still be strong mythos-based resistance, but that’s to be expected—and it’s precisely what a Nuremberg-style trial is for.

Second Theory of the Crime: Torture Was Not Effective

Despite widespread beliefs to the contrary revealed in Pew’s poll, this is the most thoroughly proven point of the Senate report. In her press release, Sen. Dianne Feinstein wrote that “The study’s 20 findings and conclusions can be grouped into four central themes, each of which is supported extensively in the Executive Summary,” the very first of which was “The CIA’s ‘enhanced interrogation techniques’ were not effective.” What’s more, the second finding was that we have been lied to about the effectiveness: “The CIA provided extensive inaccurate information about the operation of the program and its effectiveness to policymakers and the public.” If the program really were effective, there would be no need to lie about it, so all the evidence of misleading the public and policymakers is further evidence of ineffectiveness as well.

Most significantly, Feinstein points out, “The committee reviewed 20 of the most frequent and prominent examples of purported counterterrorism ‘successes’ that the CIA has attributed to the use of its enhanced interrogation techniques. Each of those examples was found to be wrong in fundamental respects.”

This is particularly true of one of the most widely known claims, that torture was vital in developing key intelligence about Abu Ahmed al-Kuwaiti, Osama bin Laden’s courier, the key figure in eventually locating Osama bin Laden. This is debunked in a section, “Information on the Facilitator that Led to the UBL Operation,” from page 378 to 400 in the report.

Feinstein makes several other key points demolishing the effectiveness claim:

- There was never a ticking-time-bomb threat that was thwarted by the use of torture.

- Torture “regularly resulted in fabricated information,” which misled the CIA.

- CIA officers regularly questioned the effectiveness of torture.

- The CIA never adequately reviewed the effectiveness of torture, “despite a recommendation by the CIA inspector general to do so and similar requests by National Security Advisor Condoleezza Rice and the leadership of the Senate Intelligence Committee.”

Remember, the pre-trial standard is probable cause, and with these points the report establishes probable cause for prosecuting crimes, and specifically refutes the theory of the crime that the effectiveness of the methods used justified them, regardless of how horrific they were. Those accused may still want to argue otherwise—but they should do so at trial, not to avoid it.

Third Theory of the Crime: Torture Was Not Necessary

From a logos-based point of view, torture couldn’t be necessary if it were ineffective—unless, of course, the purpose of torture was something else entirely—as, indeed, we now know it was. But the naive, stand-alone claim that torture was necessary, regardless of whether it was effective in gaining accurate intelligence, cannot be sustained logically. So there’s really no logical need to discuss evidence related to this claim.

But because it’s a prominent part of the public debate, more is required. We need to consider the claim as a matter of pure mythos—in terms of what it may mean to people. First, we should note that the claim can have significant psychological appeal, particularly to those who1) feel deeply threatened, 2) feel helpless and 3) are psychologically incapable of admitting their fearfulness and helplessness. Torture may “work” psychologically for them, and the broader claim that it worked to stop terrorist attacks is simply an affirmation that, thanks to torture, they now feel back in control. Confronting and replacing this element of mythos in our national psyche is one of the key purposes that Nuremberg-style trials would serve.

Second, we should note that even if it were the case that “torture worked” in some cases (which hasn’t been shown) alternatives clearly were available, which means that it still was not necessary. As he has testified to Congress, then-FBI Agent Ali Soufan was getting valuable information using traditional interrogation techniques when Abu Zubaydah—the first high-value al-Qaida target—was first captured, before ineffective torture techniques were begun by the CIA. Thus, in this very first case, even if torture had been effective, it still would not have been proven necessary.

As already noted, there has never been a ticking-time-bomb threat that was thwarted by the use of torture—except of course, on Fox’s “24,” where it happens all the time. This is clearly an extremely satisfying fantasy for some, and it’s not hard to understand why. But it is a fantasy—an example of mythos with no grounding in logos, and one of the main reasons for holding Nuremberg-style trials is precisely to force us to relinquish such enticing, but dangerously mistaken fantasies.

Fourth Theory of the Crime: Torture Was Carefully Calibrated

The claim of careful calibration is also, ultimately, logically dependent on the claim of effectiveness. Carefully calibrated futility is still futile, and the fact that it’s futile renders the careful calibration utterly meaningless, if not Monte Python-style absurd. Still, one could at least argue for starting out with prudential guidelines of some sort, regardless of whether they could ultimately be grounded in any measure of effectiveness. Perhaps one could be right for the wrong reason … right?

The moral significance of this argument is that a calibrated approach to torture would be evidence of a morally serious purpose, as opposed to anything from boredom and incompetence to sadism. Add to that a sincere—though misguided—belief in torture’s effectiveness, and you just might wriggle out of a criminal charge, claiming a lack of criminal intent.

All that is why it matters that the CIA’s torture program was not carefully calibrated—and that the CIA lied about it as well. Indeed, the third of Feinstein’s four main groupings of findings was that “The CIA’s management of the program was inadequate and deeply flawed” and one of the points under this heading specifically dealt with severe personnel inadequacies:

The CIA did not employ adequately trained and vetted personnel. The CIA deployed individuals without relevant training or experience. CIA also deployed officers who had documented personal and professional problems of a serious nature—including histories of violence and abusive treatment of others—that should have called into question their employment, let alone their suitability to participate in the sensitive CIA program.

What’s more, under Feinstein’s fourth main finding, that “The CIA program was far more brutal than the CIA represented to policymakers and the American public,” the report directly refutes the calibration frame:

Records do not support CIA representations that the CIA initially used an “an open, non-threatening approach,” or that interrogations began with the “least coercive technique possible” and escalated to more coercive techniques only as necessary. Instead, in many cases the most aggressive techniques were used immediately, in combination and nonstop. Sleep deprivation involved keeping detainees awake for up to 180 hours, usually standing or in painful stress positions, at times with their hands shackled above their heads. The CIA led several detainees to believe they would never be allowed to leave CIA custody alive, suggesting to one detainee that he would only leave in a coffin-shaped box.

Of course, the accused should be free to dispute these findings. That’s what a trial is for. But the Senate’s findings clearly contradict the “carefully calibrated” theory of the crime, and constitute probable cause that criminal conduct was involved.

Fifth Theory of the Crime: Torture Was Carried Out in Good Faith

The good faith argument is not usually made by torture apologists, but it has been made by President Obama, as noted above. Beyond running afoul of the Nuremberg Principles, there’s plenty of evidence in the Senate torture report that people were not acting in good faith.

As pointed out above, the CIA itself was aware from the beginning that there were standards for it to uphold—standards it would then go on to violate. There was also evidence of careless mistreatment of prisoners, gross mismanagement, lying to Congress, misleading the White House—the list goes on and on—all of which is simply incompatible with the notion of people “acting in good faith.” Again, there may be individuals who were acting in good faith—although this still doesn’t change the Nuremberg Principles. But the proper place to sort that out is at trial.

This is yet another case in which the power of mythos is much stronger than logos. In particular, mythos often expresses a hunger for heroes, which is clearly at play here. In the message cited above, Obama said:

The men and women of our intelligence community serve courageously on the front lines of a dangerous world. Their accomplishments are unsung and their names unknown, but because of their sacrifices, every single American is safer. We must protect their identities as vigilantly as they protect our security, and we must provide them with the confidence that they can do their jobs.

This may be so. Or it may be the case that our intelligence community is largely responsible for making it a much more dangerous world than it otherwise would be. They certainly made Iran and its environs more dangerous by helping to depose the lawfully elected Mosaddegh government back in 1953, and replacing him with the shah, for example. Still, there are surely many individuals who deserve the praise Obama offers, whatever our quibbles with the wording. The problem is, by protecting those who’ve betrayed our values, Obama is praising precisely the wrong “heroes.” At the Nation, historian Jon Weiner wrote a piece highlighting some of the real heroes of this era, who are mentioned in the Senate report. One I’ve already mentioned—Ali Soufan. Here’s a bit of what Weiner said about some of the others:

Another hero: Alberto Mora. As general counsel of the Navy in 2004, Jane Mayer reported, he tried to stop the torture program. He told his superiors at the Pentagon that the Bush torture policy violated the Geneva Conventions’ prohibition of torture and “outrages upon personal dignity, in particular humiliating and degrading treatment.” He described the Bush program as “unlawful” and “dangerous”….

Some of the heroes were ordinary soldiers, like Sgt. Joe Darby, who first revealed the Abu Ghraib abuses. As a result,” Luban points out, he “had to live under armed protection for six months.” Others were high officials, like Philip Zelikow, an adviser to Condoleezza Rice, who, Luban reports, wrote an “anti-torture memo” that the White House “attempted to destroy”….

Finally we have the case of Guantánamo prosecutor Lt. Col. Darrel Vandeveld, who refused to prosecute a teenager who had been abused in US detention in Afghanistan and Guantánamo. For that decision, Jameel Jaffer and Larry Siems report, Vandeveld was “barred from the prosecutors’ office, confined to his residence and threatened with dismissal from the Army.”

While there’s no doubt that Nuremberg-style trials would be difficult for us as a nation, those trials would not be all doom and gloom. Heroes such as these would also play a part in the proceedings. Their voices would be heard, their stories would be told, their shining examples of fidelity to America’s highest values under the most difficult of conditions would provide us with exactly the sort of heroes that we need to write the next chapter of America’s ongoing quest for perfection. They are the ones who will help us craft a mythos that’s in harmony with the logos of the underlying facts, not twisted and distorted in direct contradiction of them. They are one more powerful reason that we as a nation need to hold Nuremberg-style trials—not just to exorcise the demons we have allowed to grow in our midst, but also to affirm and empower those who fight against them—and to ensure that their numbers will grow in the days that lie ahead.