By nearly any account, 2014 was not humanity’s finest year. There was ISIS, Ebola, the torture report, #CancelColbert, our seemingly unstoppable march into the climate change abyss and so much more. Still, nothing can improve a view quite like a change of perspective, and if we rewind about 100 years or so, things are looking maybe not quite good… but better! Not launching a global conflict on the scale of World War I is definitely better.

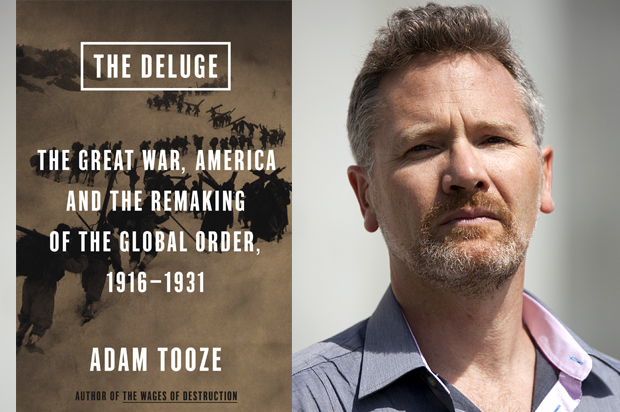

As indicated by the title, Yale historian Adam Tooze’s latest book, “The Deluge: The Great War, America and the Remaking of the Global Order, 1916-1931,” doesn’t start quite so long ago, when the war first began, but rather begins in 1916, a year before U.S. President Woodrow Wilson threw his country into what was then known as the Great War. Besides being a globe-spanning and wide-ranging examination of how America’s historic decision to join that epochal war changed the U.S. as well as the entire world order, “The Deluge” is also a look at a past that is both terribly remote and hauntingly familiar.

Recently, Salon spoke with Tooze over the phone to discuss his book, how it’s related to his earlier, contrarian work on Nazi Germany, and why the world of 100 years ago is beginning to look more and more like our own. Our conversation is below and has been lightly edited for clarity and length.

Beyond the centenary of the start of the Great War (a.k.a. World War I), what was it that made you want to write this book? What do we still not fully grasp about this enormously important moment in modern history?

One way of thinking about “The Deluge” is that it’s the prequel to another book I wrote on the interwar crisis, which focused on Adolf Hitler and Nazi Germany. In that book, I’d made the bold claim that the main threat to which Hitler was responding was not the rise of communism, as is commonly supposed, but the prospective advent of American power and the prospect of a world dominated by American power. What I felt was that I really had to make good on that claim beyond the history of Nazi Germany and examine the ways in which all of the major powers around the world responded in the early 20th century to the rise of American power.

The moment at which this becomes evident to decision-makers and powers in London and Tokyo and Berlin is 1916, the middle of WWI, at the moment where it becomes clear that the Europeans cannot decide the struggle between themselves. You can see, really, across the world at that moment, the key decision-makers reevaluating their strategic options and beginning to calibrate a new set of strategies for a world which is going to be shaped fundamentally by the United States. The endpoint of that story is the Great Depression, where that first advent of American power suffers a catastrophic shipwreck. That’s, of course, also the moment at which Hitler rises to power.

So this book really is a comprehensive examination of that first moment of realization that the modern world will be shaped by America.

Most Americans grow up thinking they’ve always been the major world power. Can you give me a sense of how, before 1916, a lot of other world powers viewed America’s role in the global order?

I think the answer is that they didn’t imagine that America did have a role in the global order. It’s not until 1913 that America acquires a central bank capable of interacting with much better-established institutions like the Bank of England or the Banque de France. It’s not until 1893 that any of the European powers sees fit to establish a full embassy in Washington, D.C. Britain is the first to do it, but before that the United States is treated as a suitable location for a consulate. In all of the accounts of the summer of 1914 and the outbreak of WWI, the United States is almost entirely absent from those discussions.

This year in Europe we’ve spent much time commemorating and discussing the outbreak of WWI, and in virtually none of those discussions does the U.S. even figure. It’s the war that transforms this, because in fighting the war, Britain, France and Russia make themselves financially dependent as never before on the U.S. Because their fighting depends on the blockade and the blockade impinges on the U.S. — and the one dimension of military power in which the United states has emerged is naval — it becomes clear that the decisive strategy … against Germany and its allies hinges on America’s willingness to go along.

There’s a really radical transformation from a position in which America is really … a nonentity in global politics to being really the decisive factor.

And this all happens quite rapidly, right?

Yes, in the space of a matter of years and months, as the war unfolds, you see this shift. At the beginning of 1916, America is still a bystander [to WWI]. By the time of the [presidential] election in November 1916, everyone in Europe is focusing on the American election to see which candidate will win, whether it’ll be [Charles] Hughes for the Republicans or [Woodrow] Wilson for the Democrats.

Wilson, really, in a matter of weeks after his election, intervenes first by blocking any further loans to Europe and then by announcing his own peace move in December 1916. From that moment onwards, the pronouncements of the American president on world affairs are essentially the most important interventions of that type by any leader. So it’s a very rapid turnaround, yes.

Tell me a bit more about how the Great Depression upended the role America played in the world starting around 1916? Did the Depression create a kind of interregnum between the world power that arose in 1916 and the one that arose again by the end of World War II?

I think the story of this book is that America becomes central to world affairs in 1916, before the … state apparatus of the American government, the fiscal apparatus, the taxing and spending apparatus, and, frankly, the military apparatus as well is capable of bearing the pressure to which world leadership is going to subject it…

[T]he more fundamental thing is that America, as it were, merges into being central in world affairs before the capacities of the American state are really adequate for that role. That’s really the tragedy that’s being described in this book, the extent to which the American fiscal apparatus’ capacity to tax and spend and lend and its ability to offer a security guarantee to its major allies in Europe falls short of what would be necessary to deal with a world transformed by the effects of WWI.

WWI was no ordinary war; WWI was a transformative event in world affairs. Part of that transformation is America’s new centrality, and there’s a sense of a time lag between the capacities of the American state and the role which that structural transformation of the international system has foisted on America.

One of the main takeaways I had from the book is that it would be a mistake to see WWI, even though it began 100 years ago, as something stuck in the past. In a lot of ways, we’re still living in the world WWI made us, no?

I think one could even go further than that and say that we’re living again in the world that WWI made, in the sense that the world in which China and India are active players in a system which faces as much toward the Pacific as it does the Atlantic … that world which, you might say, slipped from view at various phases during the Cold War … that world is actually the world that was made in the first decades of the 20th century.

For me, coming to this as a historian who’d previously worked on the 1930s and ’40s and grew up in Europe in the 1970s and ’80s, to discover the world of the period between 1916 and 1931, in which China was an absolutely key part of grand strategy for the British, the Soviets, the Americans and, of course, for the Japanese … that world is in many ways more like the world of today than the world that ended in 1989 with the fall of the Berlin Wall.

It’s not just that we still live in the world; we’re kind of back again in the world of the early 20th century.

For people who are not very informed about history, should the fact that we’re back in a version of that world again make people nervous?

I certainly think that some of the complexities we see in the current international order — the tensions that we see in East Asia between Japan and China, the reassertion of Russian ambition and aggression that we see in the Ukraine, the troubles in Europe with regard to the project of European integration … What certainly is the case is that history is on the move again. The idea that we’d reached a final system of organization was clearly overly optimistic. That, I think, is haunting.

I also think … that the West then, as now, has undoubtably the strongest cards. We have the strongest, … most resilient political systems; we have by far the richest economies in the world; we have the most dynamic systems of cultural production, of scientific research, and so on. All of this was true in the aftermath of WWI as well, and yet, nevertheless, Britain, France, the U.S. and Japan … managed to blow it. They managed to fail in their efforts to establish a legitimate and durable economic, political and military order.

I think that is a challenge which faces us in the present as well. There’s much talk now of Chinese overtaking [the world], of the weakness of the West, but I think those are almost all self-inflicted. That, too, is part of the provocation of the book — to stress that the crises that did happen in 1914 and in the interwar period, these are not inevitable crises. They’re the result … of a political failure; and that challenge is one that still faces democracies today.