By all accounts, I’ve lived a blessed life. I was born a healthy, reasonably attractive, intelligent, charming, athletically talented white male in the most prosperous country in the history of the world. I feel like the world has been my oyster and I’ve had my choice of modest pearls—even if I’ve occasionally thrown some before swine.

I am also an atheist. And according to a recent study published in The Journal of Applied Social Psychology, atheists are the most reviled group in America today. The study noted that the political bias against atheists is accompanied by “distrust, disgust and fear, thereby suggesting that the affective content of anti-atheist prejudice is both broader and more extreme than prejudice against other historically disadvantaged groups.”

But I’ve never suffered any prejudice in the 15 years since I came out as an atheist. Though I’ve only recently begun to venture publicly into the culture wars with my blog and published articles, I’ve never been shy about being an atheist. Despite frequent conversations with family, friends, and colleagues, my atheism has never affected my personal or work relationships. However, there are some atheists who compare atheism to the civil rights movement of black Americans in the 1960s or LGBT individuals in the past few decades.

I don’t think that’s an accurate characterization. Despite the fact that atheists are the least trusted group, and viewed by Americans as coldly as they view Muslims in a post-9/11 world, it’s self-evident that atheists haven’t suffered the breadth and depth of discrimination that other minorities have. Atheists can vote, get married, be high paid CEOs, and are unlikely to be unjustly killed for wearing a hoodie—unless they also happen to be black.

But there’s another, more fundamental reason why comparing the atheist movement to civil rights movements is a case of comparing apples and oranges. Being black or gay isn’t something someone chooses. Viewing the problem this way helps make sense of Protestant America’s especially negative attitude toward atheists—in their mind, atheists choose to reject God, an unforgivable sin.

It also helps us understand the best way to advocate for atheism, or at least how not to. If atheists are already viewed with “distrust, disgust, and fear,” then adopting a stance that exacerbates that image only makes things worse. Yet atheist writer and blogger Adam Lee has written:

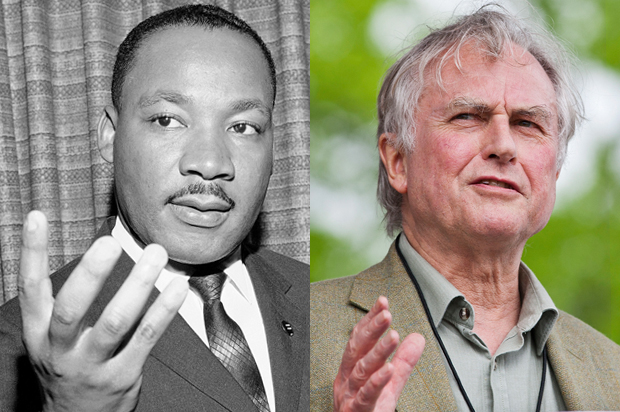

“When it comes to organized atheism, there’s room for both diplomats and firebrands. We need both people who are uncompromising in their critique of religion as well as those who can serve as the friendly face of secularism. You can see this dynamic in other successful social change movements. The American civil rights movement, for example, had both Martin Luther King Jr. and Malcolm X.”

Another atheist writer, Greta Christina, concurs. In writing about LGBT equality, she notes that “mild-mannered” lobbyist groups like the Human Rights Campaign were balanced by the more in-your-face groups like ACT UP and Queer Nation. She claims that “in retrospect, it seems clear that both methods were effective.”

Whatever your beliefs on the efficacy and merit of radicalism, there can be no confusion about the vast differences between the struggles faced by black and gay Americans and those faced by atheists. On the one hand, you have entire populations of people subjected to systematic discrimination, intimidation and violence — in short, to a system with a vested political (and often times economic) interest in subjugating and denying the humanity of black and gay Americans. By contrast, while the Christian right’s attempts to insinuate their faith back into the public domain are dangerous, and should be defied, they typically don’t carry with them the same grave consequences as those suffered by other disadvantaged communities. Nor are the burdens of the Christian right’s advances borne by atheists alone, but by anyone who doesn’t prescribe its hardline, fundamentalist leanings — a class that includes people of all minority denominations (not to mention anyone with a uterus).

An exclusively atheist radicalism — inspired in particular by the work of civil rights leaders, past or present — doesn’t just diminish the unique historical struggles of black and gay Americans. As we’ve seen in the rhetoric of people like Bill Maher and Richard Dawkins, a strategy of radically inflected “firebrand” advocacy also threatens to alienate and antagonize vast portions of the population.

Like both Lee and Christina, I believe that an unflagging and even passionate advocacy is necessary to move the narrow window of social and political acceptability, it’s just that we atheists need to be extra careful in how we do it. Because we’re perceived as choosing to reject longstanding societal norms, instead of doing something that’s largely beyond our control, we risk creating a backlash that will only hinder our progress.

By comparing atheism to a civil rights movement, I believe atheists are digging in the wrong place, to quote Indiana Jones. It’s not our rights that are being trampled, it’s our reputation. And as writer and skeptic D.J. Grothe wrote, atheists “need a public awareness campaign, not a liberation movement.”