Daniel Lanois’ new album, “Flesh and Machine,” opens with a short overture called “Rocco,” which casts a powerful spell almost instantaneously. Over a progression of gentle piano chords, something that sounds like a human voice coos and quavers queasily, its tone distressed but delicate and beautiful. It immediately ushers you into the world of “Flesh and Machine,” and like so much ambient music, “Rocco” may be best heard at low volume. It should coalesce with the other sounds around you: a dog snoring, a car driving by, birds in a tree outside the window, the heater kicking on.

Just as “Rocco” fades into the room, Lanois abruptly breaks the spell with “The End,” a rumbling and visceral number that sounds like a fight between drums and guitar. The transition is jarring, but useful as it delineates the extremes of flesh and machine; much of the album is gentle and quiet, but much of it is also violent and loud. All of it, however, is inventive and nuanced: ambient music at its most ambitious and innovative. From the gauzy nostalgia of “My First Love” to the runaway patter of “Opera,” “Flesh and Machine” is one of the most immersive albums of the year — the kind you can crawl into for a few days. It’s also far and away Lanois’ best work to date.

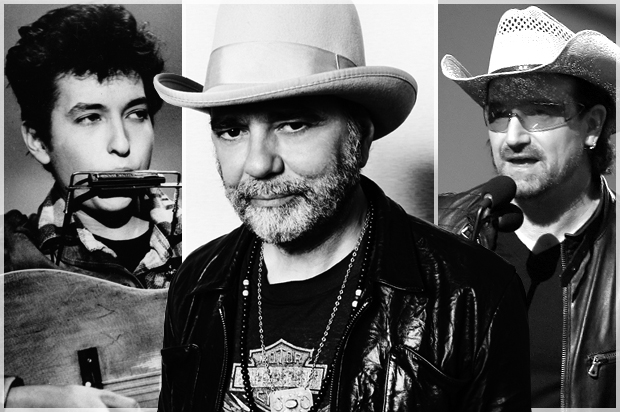

For 30 years Lanois has been one of those people who lurks just behind the scenes of popular music. He started making records as a teenager in his mother’s basement in Ontario, mostly working with local acts (including notorious children’s singer Raffi). In the early 1980s he worked with Brian Eno on a series of ambient and pop records, most notably U2’s pair of breakout albums, “The Unforgettable Fire” in 1984 and “The Joshua Tree” in 1987.

Despite ushering that band from obscurity to ubiquity, his best work has been with such older artists as post-Genesis Peter Gabriel, Bob Dylan, Emmylou Harris, Neil Young and Willie Nelson, as he gingerly updates and expands their musical palettes. On his best work — Harris’ 1996 album “Wrecking Ball” and Dylan’s 1997 comeback “Time Out of Mind,” for instance — he creates a roominess that generates a natural reverb and evokes a live performance, yet he purposefully upsets the balance between the old and the new, the organic and the synthetic. The result is music that sounds placeless and timeless, simultaneously old-fashioned and futuristic.

On his own albums, however, he has rarely shown so sure a hand. He is a capable songwriter, even if 1993’s “For the Beauty of Wynona” and 2003’s “Shine” place too much emphasis on words and too little on sound. “Belladonna” in 2005 was too constrained by its concept, which was inspired by a trip to Mexico. But “Flesh and Machine” is his most wide-ranging album to date, and also his most beautifully nuanced. On tour recently, he unveiled a series of new short films created to illustrate these 11 new songs, which illuminate some of the trippier elements of the music. When Salon spoke with Lanois recently, he was eager to talk about the visual components of “Flesh and Machine,” which he hopes will be “the headphone-listening, drug-taking record of the decade.”

Tell me about the visual component to this album.

I’ve always loved film, so we tried an experiment. We sent some filmmakers some of the tracks from the new record, and they provided some films to run in tandem with the songs. Some lovely new surprises. We’re rolling with that right now and having some fun with it. Jim McKay came up with a beauty. He filmed his daughter dancing in the forest to a piece of mine called “Iceland.” What’s fun about this is that we have invited some known and professional filmmakers, but we’ve also posted some tracks for amateurs to build films around. So we’re getting both ends of the spectrum. We’ve already gotten a couple of amateur ones that stand up nicely. There’s something sweet about the resourcefulness of all this — just to celebrate somebody who might not be known might be good for everybody. I’m so excited about it because it’s really an opportunity to do something renegade. As we all know, making films is not easy, and having them be viewed is even harder. If we can show something on a website or during a show at a theater, it might be the tip of an iceberg for a filmmaker.

How does this fit into the live show?

The electro part of my set is expanding, where I bring the studio to the stage and show prepared films on a screen. One of the showings is an early animation disc that precedes film. It’s 150 years old. It’s drawing spinning on a disc, and they create this animation that you look at through a shutter. We refilmed the drawings and assembled them and they’re really beautiful — very simple but colorful and full of wonder. There’s something very endearing about them, like early Disney animation. They have that tonality and charm. That’s one of the things we’ve been showing, and people just love it. It really resonates during these fast times.

Are you thinking visually when you’re writing or recording?

The images do come to my head once the song comes into play. There’s a very rhythmic track on the record called “Sioux Lookout.” The toppings are very chantlike, and you don’t know if they’re vocals or orchestral instruments. The sounds are not that familiar, and there are moments where you think, Am I hearing an animal or am I hearing a human? They’re not lyrics, but they are vocal sounds. I started having this sensation of a contemporary native chant. I grew up in Canada near the one of the reserves, and I’ve always had a fascination with that world. Part of the native philosophy is to live in harmony with our relatives — not just our human relatives, but the with the winged people, the water people, the four-legged people. It started sounding like a chant that was representing all of those relatives. I’m quite proud of that one in the sense that you don’t know exactly what you’re hearing, but the emotion you feel from it is the emotion you get from someone singing. It’s creating what I hope will be a universal language. I think when we don’t understand the specifics of a language, we still respond to the emotion. People listen to Tinariwen from Mali and may not understand exactly what they’re saying, but we certainly feel what the singers are feeling.

This is your most purely ambient record in a long time, even more so than 2005’s “Belladonna.” Did you conceive it as an extension of your previous ambient work with Brian Eno?

There’s a track called “Forest City” that’s quite stylistically similar. It’s an ambient textural piece later on the record. When I met Brian Eno and we went on to record a lot of ambient records together, I really admired that he had devoted himself to that direction. It was a version that he felt very strongly about, and at that time it seemed quite outside the mainstream and esoteric. I respected his commitment to something that was not going to be very commercial, but those records are beautiful and they have lived on to become part of the continuation of contemporary ambient music. I’ve applied that philosophy to the new body of work. By letting myself off the hook of conventional songs, I was able to investigate the sonics and really pour my energy into the invention of new sounds. I’m not suggesting that I pulled it off, but I’m interested in the future of music and in creating sounds that have never been heard before. When I wake up in the morning, that’s what I think about. It’s part of my quest. I may come back to lyric songs at some point, but that’s what’s driving me now.

It seems like that could apply to most of your projects, especially on something like “Wrecking Ball” or “Teatro,” which are rooted in traditional music yet sound very innovative.

That’s a great compliment. Even when you’re working in a conventional structure with someone like Emmylou or Willie Nelson, two great traditional American singers, you have to respect and embrace that but also think about stepping into the future and allowing such an artist to embrace new sounds and provide new sensations to their listeners. With Emmylou, I thought she shouldn’t be restricted by any kind of Nashville preconception about what girl singers should be doing. People can do different things. Jimi Hendrix did some country songs, but they had a twist to them. That’s why we visited “May This Be Love,” which is kind of a country song. We built this whole soundscape into a new arena. It wasn’t easy to do, but I think we pulled it off.

With Willie, I asked him what it was like when he got started as a kid, and he said he was in a dance band in Texas. That image was so fascinating to me, and when I recorded “Teatro,” I replicated a dancehall for him. At the time my studio was a big old Mexican cinema that I had taken over, so we had all this space to work with, essentially like a soundstage. We brought in some risers and lots of bleachers from the Mexican restaurant across the street, and built a place that looked like a dancehall. What was nice was that it meant he didn’t have to be in another conventional studio one more time. He was really touched by the effort that we had gone to to provide this feeling. We were able to work quickly, but it wasn’t like we were just doing another record. “Teatro” is a little more Spanish. It has a little Django Reinhardt in it, and it has some freedom in it because the musicians weren’t being trumped by any kind of clinical studio environment.

I try to sidestep what’s most familiar, because if something is very familiar, we likely have had enough of it. Isn’t it nice when works live on and keep being fascinating to listeners? I think we can hold our heads up in regards to Emmylou and Willie. You could put on those records and be transported to a special place.

Tell me about the album title. What made that phrase stand out to you?

It represents the line that I’ve always walked. It’s necessary for things to be hand-played, for that kind of authenticity to be part of the work. But then the studio is all about machines — microphones and pre-amps and processing boxes, recording formats and all that. That’s my domain, and I have a great deal of respect for it. Still, you can’t do something harsh and clinical and think that’s going to be all okay. So “Flesh and Machine” stands for that struggle that I’ve always had in my life: how to embrace technology and still have it serve the human, how to make sure the work will have soul. I think this album addresses that issue and grabs technology by the throat and says, Okay you motherfucker, come on! I’m going to knock you down, melt you down. I’m going to be the Geiger of the sonic world. We’re going to build the set of “Alien” all over again. And I’m not going to hide the fact that we’re working with machines. The machines are going to be part of the flesh. Flesh and machine.

Is there any connection between that title and your recent motorcycle accident?

I never thought about it, but I’m going to work with it. Thanks. That fucking HP2 Megamoto broke ten bones in me, and l’m still riding the thing! We have become one. Flesh and machine. Hey man, when you have an accident like that, you’re certainly reminded that you’re made of flesh and bone and that we live in a fast world and it’s only getting faster all the time. I like a bit of speed for technology in the studio, but I don’t like it on the road. It’s madness when people are so preoccupied. Don’t text while you drive. Of course. But what about eating? What about working your GPS? What about slapping the kids in the backseat? It’s incredible the amount of things we try to do while we drive.

Or while we walk. I live in a college town, and it takes all my concentration to avoid the students walking blindly into the road.

Yes, because a lot of them are crossing the street as if to say, I own the street because I’m a pedestrian and I get to plug anything into any orifice and I still command the crosswalk. Whatever happened to [sings] Just remember the safety rules. Stop. Look. And Listen. I talked to Brian Eno about it and he said, [in an exaggerated English accent] It’s very simple. People should pay attention. He wasn’t talking about driving only. He was talking about your work, your lover, what you read, what you write, what you eat. We’ve largely stopped paying attention because we’re rushing around trying to cram so much in. We think the next thing around the corner is going to be more interesting than the thing in front of us. To pay attention, as simple a thought as that might be, really applies to our times.

That idea seems to apply to the album as well. It doesn’t just sit in the background as part of the room, as ambient music is often designed to do. Instead, these songs make you pay attention.

I like the analogy. That’s why I work with Brian Blade. He’s one of the world’s greatest drummers. He’s just so committed. To watch him is a fascinating experience in itself. It’s nice to appreciate the beauty and the elegance of such an artist. Life should be like that. Everything should be significant. Just like I significantly choke a smoker when he throws his cigarette onto the sidewalk. You motherfucker! We’re trying to have a clean city here. Just ’cause you smoke, you think you get to whip your butt on the ground and it’s going to go down to the sewer. Those filters aren’t biodegradable. Just pay attention to your habits and what you believe in. Who are you? What are you doing? What are your expectations? Where do you want to go? Are you doing it in a respectful manner?

How did I get there? I don’t know. Getting back to my record, I feel like my devotion as a sonic specialist and my quest is the same as it’s always been. I’m trying to take people on a journey with my work and have them look at life a little differently than they did before they listened to the record. Raise their spirits a bit, maybe get them out of their heads or our of their skins somehow. I think it’s a pretty good drug-taking record. I’d like for it to qualify for the headphone-listening, drug-taking record of the decade.

Which drug would you recommend?

I’ve stopped all that myself, because I’m a bit old. I think just good old-fashioned California pot will do. But you’re in a campus town, why don’t you ask a few people and call me back?

I’ll see what I can do. Some of these songs sound like they might accentuate that high, especially the distressed guitar sound on “Aquatic.”

“Aquatic” is very psychedelic and distorted and tormented. I wouldn’t even say it’s a good sound, but it’s really unsettling. It’s emotional and it’s just crying to be saved. I called it “Aquatic” because it sounds like somebody’s underwater. Maybe they’re drowning and they’re trying to latch onto something. The current is taking them away, but here comes a school of fish [makes bubble noises]. You keep coming up for air, but the waves drag you back down. There’s something submerged about it. It reminds me of San Francisco and some of the old guitar sounds that came out of that experimental psychedelic time.

When you’re working on a song like that, do you have that sound in your head and work to make it real? Or do you just explore and find that unexpected element along the way?

On “Aquatic,” that sound is my steel guitar. An old friend. I have a good time playing that instrument, but that performance was a very overdriven sound filtered through my favorite amplifiers, including a vintage Fender Basement amp from the late ’50s. It’s a box that I use to send an echo through one amp that’s dry on the other end, and it was so loud that I had to play very lightly. So you get these intriguing harmonics. It took on a life of its own. It was a very long performance that I edited down to a sensible length. Andy [Kaulkin, who founded Anti Records] tried to talk me out of putting it on the record. He told me: Man, it really bums me out. I said: Andy, you have to think of it as an emotional phase canceler. If it sounds that depressed, it’ll suck the depression right out of the listener and you will leave the record a happier, more cheerful person. So he said okay.